What Makes IP Valuable?

A First Principles Examination

You don’t need to live in Hollywood to recognize that IP is the new oil. As I wrote about in the Imagination Economy, the atomic unit of entertainment properties is no longer the movie, but the franchise.

But change is afoot. Seemingly out of nowhere, an entire new class of media properties built atop novel Web3 meta-containers such as NFTs and DAOs have exploded onto the scene. Bored Ape Yacht Club, CryptoPunks, Loot, Nouns, and more prophesize the dawn of a new age: one where IP ownership and media creation is completely decentralized, and where financialization and new mechanisms for orchestrating narrative governance promises better entertainment and more valuable IP.

Very quickly, the prophesy appeared to become true. In March 2022, Yuga Labs, the creators Bored Ape Yacht Club, was valued at $4 billion, ironically the same valuation (not adjusted for inflation) that Disney paid for Marvel in 2009 and Star Wars in 2012.

This seemed, to me at least, suspect. Not because I don’t believe in the potential of decentralized media and Web3 franchises, but because I struggled to equate the value of BAYC with that of Star Wars.

I know what Star Wars is. It’s the movies I’ve watched dozens of times. It’s Luke Skywalker and Obi Wan Kenobi and Darth Vader and the Lightsaber toys that me and my brother would battle each other with. Star Wars is a galaxy far far away. It is IP that I, and hundreds of millions of others, would rabidly consume because of the entertainment utility it creates.

What Bored Ape Yacht Club content did I consume? Is there even any to consume? Is it any good? Is that important to the value of IP? Does it matter who produced it? Does it matter if I owned it?

I was left with many questions.

This essay is Part 1 in a two-part series aimed at answering some of these questions. Mainly, we will focus on answering the following: what makes IP valuable? In particular, I will seek to strip to the core and understand IP production and value creation from First Principles. As I do, I will surface a few Principles that I believe to be fundamentally true as it relates to IP.

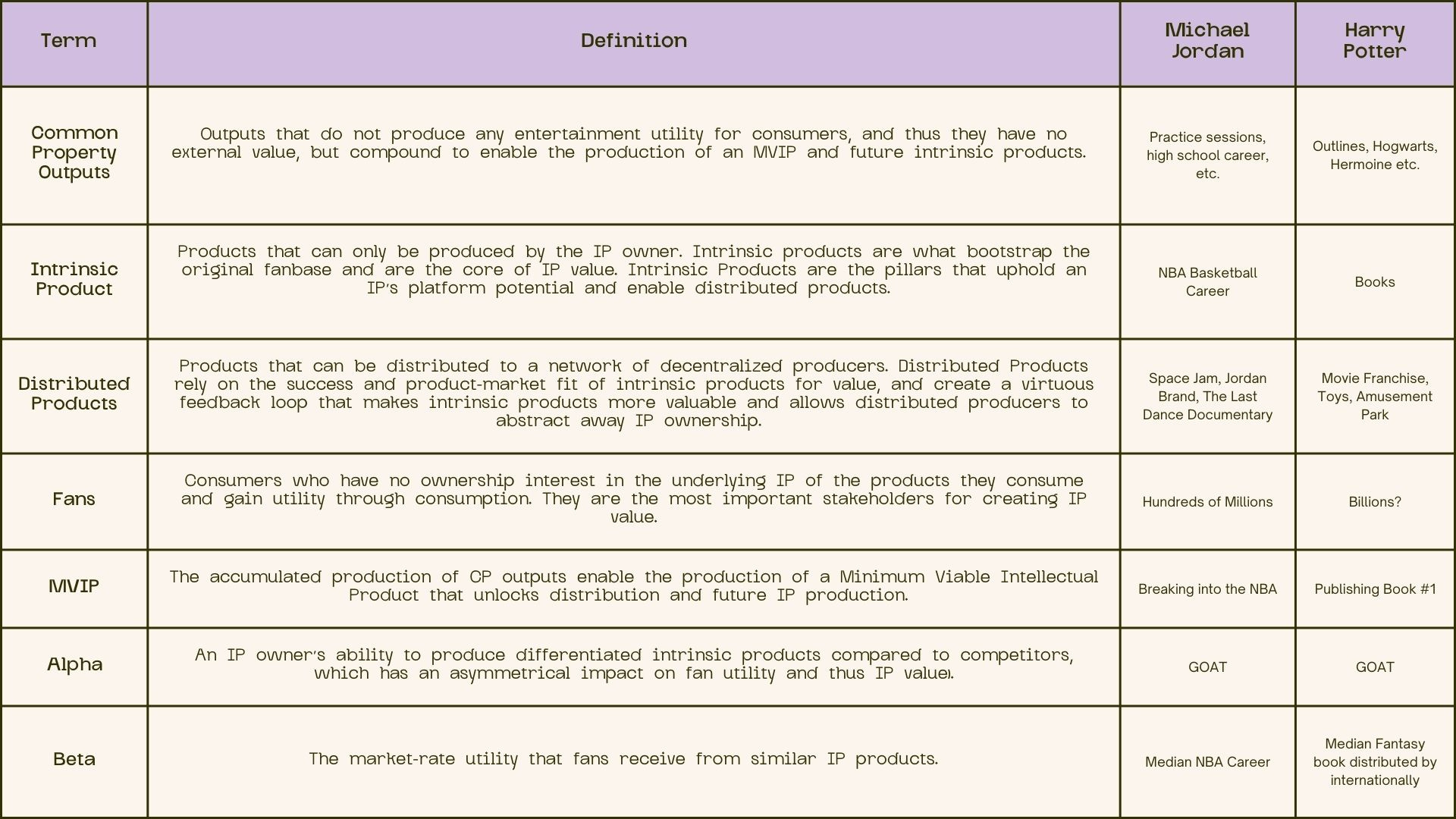

To begin, let us start by defining a few relevant terms that will help answer this question.

Principle #1: All IP begins as ‘Common Property’ that depend on the verticalized, compounding production of commoditized parts.

Products that distribute IP are not created from thin air, but requires the highly precise production and assembly of ‘Common Property’ outputs. These outputs, in turn, require their own manufacturing process that precedes any IP production.

Common Property Outputs are outputs that do not produce any entertainment utility for consumers, and thus they have no external value, but compound to enable the production of an MVIP and future intrinsic products.

Producers manufacture these outputs using resources and raw materials that are intangible and nonfungible — their imagination, thoughts and dreams.

These outputs are a necessary factor of production that are essential to one day enable the future production of intrinsic products that create utility for consumers (more on this later). They are the drafts, outlines, practice sessions, high school games, rewrites, late nights in the gym, broken pencils, dirty sneakers and on and on that are worthless to everyone else but valuable to the producer.

Indeed, For IP producers like JK Rowling and Michael Jordan, these outputs are essential steps along a journey to materialize the worlds, stories and dreams that exist inside their imagination, a future state that cannot come to exist without the production of these outputs and parts.

But with each production run — each outline, each practice, each step of the journey — the producer becomes more skilled, as each marginal production run builds on top of the previous, thereby accumulating and compounding.

I've missed more than 9000 shots in my career. I've lost almost 300 games. 26 times, I've been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I've failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.

- Michael Jordan

JK Rowling began scrawling a few ideas about an orphan with a lightning-bolt scar on a napkin. Michael Jordan started shooting basketballs in his driveway. For the most part, anyone could do those things and thus these outputs were undifferentiated.

Indeed, these outputs did not produce any entertainment utility for consumers, thus they had no commercial value.

For an IP product, part or output to have commercial value, it must create utility for fans — individuals with no ownership interest in the IP who gain utility through consumption.

Yet, the production of Common Property outputs is necessary to one day enable the production of an MVIP (Minimum Viable Intellectual Product) and subsequent intrinsic products (playing in the NBA, publishing a book) that unlock the ability to distribute the IP to consumers.

The accumulated production of CP outputs enables the production of a Minimum Viable Intellectual Product that unlocks distribution and future IP production.

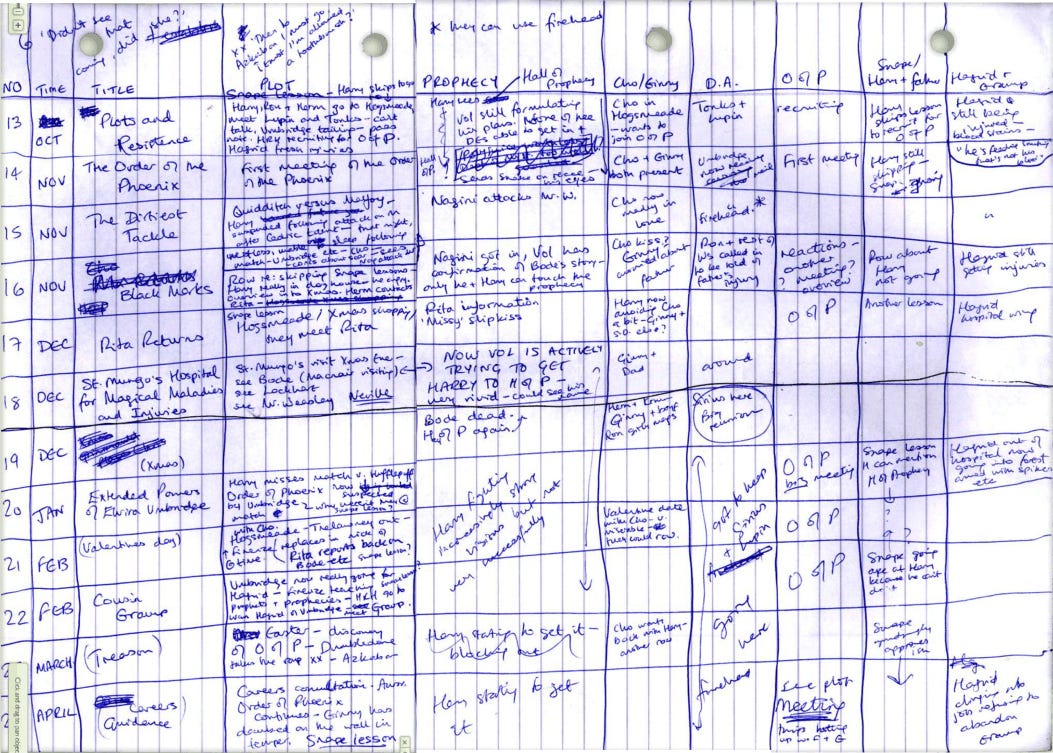

Michael Jordan had to get to a point where he was skilled enough to be in the NBA as that represented the platform from which he could distribute and monetize his skill as a basketball player. JK Rowling had to determine the nuances of each character, the story's conflicts, its structure, etc. to get to a point where the story was good enough to produce a book that she could distribute and monetize. The same holds true for George R.R. Martin, Walt Disney, Stan Lee and the other great ushers of IP.

Furthermore, the form factor of the MVIP has historically been determined based on the threshold of differentiation set by the distributors.

Differentiation is defined by two specific intrinsic and reflexive outputs of the this production process: skill and scale.

Let’s begin with skill (or precision). A basketball player has to reach a certain skill level to be drafted or signed in the NBA and distribute their IP (their basketball career) during NBA games and seasons. People like to watch the NBA’s basketball players over the United Basketball League’s, as the NBA has proven to attract the best players (market beta) which is critical for entertainment utility (more on this later). Similarly, a movie or literary work has to pass through editors, producers, studio heads and months of post production before the IP can be distributed to consumers over the traditional rails (cable, box offices, streaming, VOD, book stores, etc.).

The second point of differentiation is scale (or volume). JK Rowling needed to write a complete book, not just a few chapters, to optimally distribute Harry Potter IP, and a basketball player needs to produce enough body of work in high school, AAU and college to demonstrate the immutability of their skillset.

This is the punch line of Principle #1: both skillset and volume (and thus differentiation) are intrinsic outputs of the compounding production of ‘Common Property’ outputs that have no commercial value.

Moving on, the scale of differentiation necessary to produce an MVIP has historically been determined based on the past behavior and preferences of demand. People liked to consume IP via books, movies, TV shows and comic books, not via an outline, or a few chapters, or a single picture.

Now, however, the disruption of traditional IP distributors via streaming and social media networks allows IP owner to have more flexibility in terms of production and distribution.

Lil Nas X, for example, is able to distribute his music (his IP) instantly by publishing a song (‘Old Town Road’) on SoundCloud and have it explode in popularity via remixing and UGC on TikTok. Previously, he would have had to wait to be discovered by a record label, who then would decide when to release his music and in what form factor — most likely as an album rather than a single.

Yet, while social media networks and new platforms have democratized production and access to distribution, it has not changed the form factor of the MVIP by much. Sure, an album changed to a song and the new types of video content (and utility) emerged on Youtube and Tik Tok, but by and large, the form factors set by legacy distributors were correct — consumers want to first interact with IP via books, comics, TV shows, video games and movies; they want the scale, context and substance1. Similarly, consumers want to consumer music IP in songs and albums, not snippets or ringtones, and they want to consume sports games — with more flexibility for highlights that can be distributed on social media networks — synchronously and of the most differentiated and best players.

These form factors exist as they are the structures by which consumers gain the most utility consuming IP products, thus distributors will refuse to distribute any other form factor or an algorithm will ensure it’s dead on arrival.

Thus, while social media networks and new media technologies have lowered the MVIP threshold by making production and distribution easier, it has only magnified the importance of product-market fit in the distribution equation.

This is because IP distribution is no longer constrained by a scarce amount of distribution channels like cable TV channels, box offices, album releases and shelf space at a book store. Rather, distribution decisions are made by algorithms that distribute content based on an approximation of what fans like, which is a more enhanced mechanism of the legacy model, where gatekeepers — instead of algorithms — would try to approximate this.

Thus, producing valuable IP, just like software engineering or advanced manufacturing, requires a highly skilled talent base that builds a capability through a sequential progression of proficiency.

Which leads to:

Principle #2: The ownership and production of Common Property outputs & parts must be centralized until the IP cements product-market fit.

The production of intrinsic products that create entertainment utility for fans is what underpins IP value. Another name for this is Product-Market Fit.

Defining what an IP’s intrinsic products is critical. For Michael Jordan, it’s playing basketball in the NBA. For Harry Potter IP, it’s the books. For Lil Nas X, it’s making songs. For Marvel, it’s comic books. For Star Wars, it’s movies.

Intrinsic Products are products that can only be produced by the IP owner. Intrinsic products are what bootstrap the original fanbase and are the core of IP value.

Until the point of solidifying product-market fit, the IP owner(s) is the only producer able to produce the ‘Common Property’ outputs that begin to demarcate the boundaries of the idea and hint at its shape, substance and potential.

Why?

Because at this stage, the IP owner has a monopoly on both supply and demand of CP outputs; only the IP owner has the technical insight to the factors of production (via their imagination) necessary to reach an MVIP, and only the IP owner receives utility from the process of production via the accumulation of skill and scale — outputs endogenous to this process.

Michael Jordan didn’t spend late nights in the gym working on his game after getting cut from his high school team so that he could sell sneakers or be paid to play basketball then and there. JK Rowling didn’t write outlines and drafts to then hopefully sell and distribute those outputs to potential fans at the time of production.

Indeed, even if they wanted to, they couldn’t. That’s because (1) nobody wanted to distribute those outputs/parts as (2) they weren’t differentiated enough to create utility for fans. Said another way, there wasn’t demand to pay Michael Jordan to play basketball in the NBA when he was 16 or to distribute Harry Potter IP across the world with only an outline complete because both lacked the necessary skill and scale crucial for product-market fit.

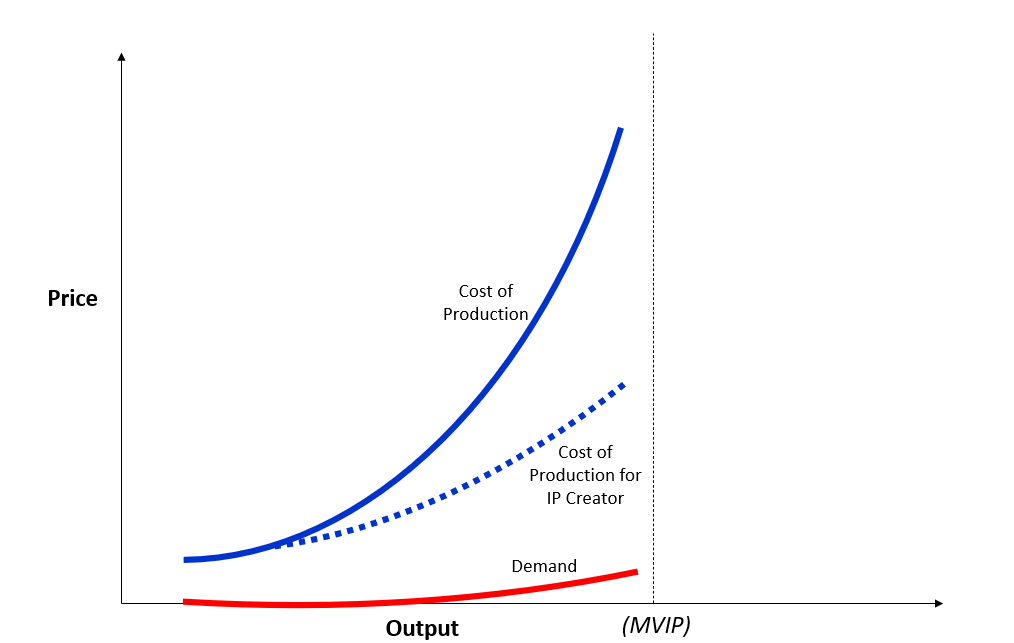

Second, for any other producer that doesn’t have complete control over the production and ownership of the potential IP, the production cost necessary to produce an MVIP is often cost prohibitive. During this period of producing CP outputs in ‘No Man’s Land’, the producer is burdened with significant opportunity and monetary costs. They are spending currency (fiat and time) to produce outputs that have zero commercial value.

So why do they do it?

As mentioned, they do so in order to reach a level of skill and scale to produce an MVIP that could unlock distribution and monetization potential, and which potentially bootstraps future intrinsic product distribution — i.e. publishing Harry Potter & The Philosopher’s Stone or making it to the NBA.

The only way to accumulate the necessary skill and scale is through the centralized production of CP outputs, and the producer gains value from the process of getting better.

Yet, there is a high likelihood of failure. Since the IP owner controls the factors of production, aligning both ownership and production incentives are crucial to its success as the IP owner has the most differentiated skills — both through access to their imagination and accumulated skills & scale developed through CP production — to produce an MVIP that has product-market fit.

If JK Rowling or Michael Jordan have less ownership over the future success of their IP, it decreases the marginal benefit of producing the necessary CP outputs to achieve the volume and skills necessary to (1) get distribution and (2) differentiate once they do.

At the same time, the decentralization of individual parts of the potential IP prior to product-market fit would create perverse principal-agent incentives.

If JK Rowling sold the rights to Hermione Granger during the purgatorial ‘No Man’s Land’ stage, she would have less incentive to invest in this character and would also introduce new stakeholders that may have conflicting creative direction and incentives as her own.

As a result, this damages the creative process and dilutes the intrinsic product (the complete book) from taking the shape that the IP creator imagined.

Indeed, while anyone can write a book using the CP parts of Hagrid, Hermione Granger, Hogwarts, the Wizarding World, and the ‘Chosen One’ mythos, only JK Rowling can write it in a way that creates a context that provides entertainment utility to billions of fans.

JK Rowling can create the best version of Hermione because she also is writing the plots of Ron and of Harry and Hogwarts and Dumbledore. Hermione written in relation to the rest of the story is superior to a decentralized production of Hermione that is written in isolation and with less context.

The IP owner's insight to the context and relation of the individual parts — a function of centrally producing each part with the highest precision — minimizes cumulative error and creates the synergies that allow for better leverage on production and potential for product-market fit with fans.

Thus, decentralizing ownership of ‘Common Property’ parts prior to the production of intrinsic ‘Intellectual Property’ products weakens the potential of the project.

Parts, like characters and basketball games, thus cannot be distributed or monetized at production because they only gain value retroactively following the product-market fit of intrinsic products.

JK Rowling has the ability to create the specific context and configuration, given her proprietary access to her imagination and accumulated skillset and scale of this specific production process, that retroactively gives each of these CP outputs fandom, meaning and value.

Imagine if Michael Jordan gave up after a year at UNC. Or if JK Rowling never finished the first draft of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. Everything they produced up to that point, every character, every outline, every game worn jersey, every hour of energy, would not have commercial value. That value is entirely dependent on some future production of intrinsic products that have product-market fit with fans, but the very process of financializing these parts and decentralizing ownership and production reduces the likelihood of such product-market fit.

Thus, any investment in these pre MVIP inventories would be purely speculative and assuming that these commoditized outputs somehow have intrinsic value that securitizes the speculation is incorrect.

Which leads to:

Principle #3: Producing intrinsic products that have product-market fit, not decentralizing ownership, bootstraps demand and enables distributed production.

How did Michael Jordan build a fanbase? How did Harry Potter? How did Disney?

For IP to build a fanbase it most first produce intrinsic products. There is no Jordan Brand or Space Jam without a highly differentiated NBA basketball career that created entertainment utility for hundreds of millions of fans, and there is no NBA basketball career without the skill and scale of years producing CP outputs.

The same holds true for Harry Potter. There is no Harry Potter movie franchise, amusement park, spinoff series and so on without a highly differentiated book series that created entertainment utility for billions of fans, and there is no highly differentiated book series without the years of JK Rowling accumulating skill and volume producing CP outputs.

This reveals a fundamental truth:

As an IP owner(s) continues producing successful intrinsic products that create utility for fans, these products begin to accumulate and compound and enable a new type of supply — distributed products.

Distributed products are products that leverage the underlying IP but are produced by a network of decentralized producers that may or may not have ownership interest in the IP.

These producers leverage the IP’s existing demand to bypass the cold-start problem. Once the IP has reached a critical mass of fandom, the IP owner can decentralize production to other producers who create distributed products that only exist because of this fandom.

It’s Michael Jordan’s basketball career (his intrinsic product) that originally built his fanbase, and this fanbase is what attracted other producers to create products that Michael Jordan could not given his skillset: Space Jam, Jordan Brand, The Last Dance, etc.

Michael Jordan, Harry Potter, Marvel or any other usher of IP no longer have to produce intrinsic products (playing basketball in the NBA) to provide utility for fans, but can become a platform that enables others to provide them with income (and new revenue streams) to leverage their IP, gain access to their fans and build new distributed products that grants the distributed producers with indirect ownership exposure to the IP (thereby decentralizing ownership).

These distributed producers have different skillsets that allow them to produce new form factors of supply that (1) create new forms of engagement and entertainment utility and (2) unlocks new channels of distribution which:

Acquires new fans;

increases the overall utility of existing fans as they have new forms of supply to consume, and;

Re-engages dormant fans.

Indeed, distributed production can create completely novel products — like Space Jam or Disneyland — or they can repurpose previous outputs into new form factors.

For example, The Last Dance documentary was able to repurpose and package pre-existing CP outputs —Michael Jordan’s practice sessions — into a new form factor (a docuseries) and distribute it to consumers. The same is true of The Beatle’s Get Back Disney docuseries.

Said another way, both of these examples allowed for unproductive assets to become productive. Michael Jordan's fans could now access the dormant CP outputs that Michael Jordan didn't have the skillset to produce in the necessary form factor (a docuseries), thereby creating more utility for existing fans (via more supply) and increasing the IP’s distribution (vis new channels of distribution) that both grows and re-engages the IP’s fanbase.

Hence, the product-market fit of intrinsic products offers the net new creation of new distributed products (like Space Jam) as well as as the ability to turn dormant, unproductive CP outputs into components of productive distributed products.

These distributed product allow IP owners to gain leverage on their intrinsic products and get more distribution, a consequence of:

New fans (more demand), and;

More products delivered (more supply).

It creates incremental form factors of supply that reinforces the value of the pre-existing intrinsic products as it adds to the entertainment utility of the IP and increases its differentiation (and scarcity).

How many fantasy books get their own movie series or amusement park? How many basketball players star in movies and have their own clothing brand?

So you have more supply (products delivered) which adds new points of consumption (and monetization) for existing fans (a Michael Jordan fan can re-engage with the IP by consuming The Last Dance; a Harry Potter fan can re-engage with the IP by consuming Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore) as well as new distribution (Netflix vs. NBA games; box office vs. book store), which acquires new fans.

Consequently, both the ARPU and number of users (fans) increases, which increases the demand from distributed producers to leverage the IP for new content, which increases the enterprise value of the IP.

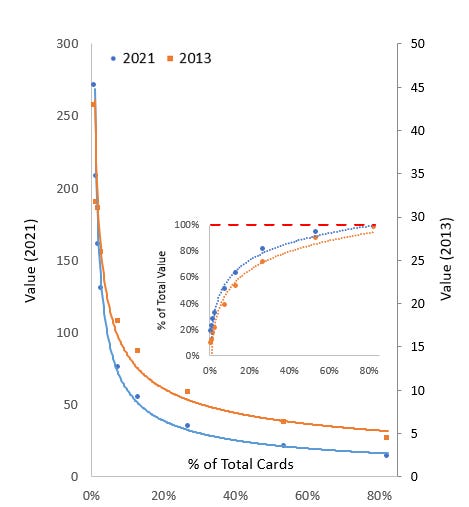

While the IP market is highly illiquid and has very inefficient price discovery mechanics, we can empirically see how this dynamic unfolds via another market: sports cards and collectibles2.

Sports cards and collectibles are examples of distributed IP products that are produced and distributed by decentralized producers, and unlike other distributed products like The Last Dance, utility is derived through ownership rather than consumption. The cards and collectibles don’t necessarily entertain but act as a quasi-financial instrument to indirectly own the IP.

Indeed, we can use this market to understand how the production and distribution of distributed products like the Last Dance impacts overall IP value.

As you can see below, the greatest relative price change of a Michael Jordan Rookie card followed the release of The Last Dance docuseries, and while the asset price continued to appreciate given the market beta, it ultimately corrected — but well above pre-Last Dance levels.

Which begs the question, why?

A collectible like a Michael Jordan Rookie Card has value because:

It’s scarce

Its relationship to Michael Jordan IP

While scarcity is an important feature, it is not fundamentally built into these products. Meaning, a Michael Jordan rookie card is orders of magnitude more valuable compared to the average rookie card not because it is more scarce, but because it is Michael Jordan.

Indeed, value accrues to the collectibles linked to the IP with the best alpha in terms of producing intrinsic products that provide entertainment utility to fans — which further reinforces the scarcity of the IP (there can only be one GOAT) and leads to price appreciation (and IP value) to accrue nonlinearly. That’s why card value follows a Pareto Distribution.

When additional products, like The Last Dance, are produced and distributed, it adds to the Michael Jordan IP and thus his relative alpha. Thus, scarce collectibles – like a Michael Jordan rookie card – and other ownership exposure to the IP increase in value.

Closing Thoughts

As the IP owner spends years producing intrinsic products and finding product -market fit with fans, they can cross the chasm and become a platform that allows them to decentralize the production of IP to create distributed products that:

Have higher production costs

Are outside of their production proficiency, and;

Are more discretionary and less crucial to the core intrinsic value of the IP.

Space Jam and the Jordan Brand are not as important to Michael Jordan’s IP value as much as his success as a basketball player is; the Wizarding World Amusement Park is not as important to Harry Potter IP as much as the product-market fit of the books.

Hence, the intrinsic products create product-market fit for a massive base of customers, which allows decentralized producers to make new products that further reinforce the underlying utility, which benefits owners of Michael Jordan IP like collectible cards, Jordan Brands, the Chicago Bulls & NBA jerseys.

Which reveals another fundamental truth: IP value follows demand, it does not create it.

We can stop here for now. In the next post, we will investigate how Bored Ape Yacht Club fits within this paradigm and try to understand how it seeks to create durable IP value.

These form factors are essential to bootstrap a fan base, and IP value, from there the IP production can be distributed via UGC and other factors of production.

Two things are critical to the price of these products: scarcity and the value of the underlying IP. The importance of scarcity should not be discounted and is why the highest-selling sports card of all time is T206 Honus Wagner baseball card ($6.6 million). Nonetheless, while not perfect, there is fruitful insight to be had.