The Imagination Economy

A New Entertainment Model, The Imagination Economy, Amateurization, and the Four Components of the Metaverse

Over the holiday I read two books that proved synergistic for this piece. The first was Joseph Mann’s The Cult of The Dead Cow, a lively investigation of the origins and rise of the famed hacktivist group of the same name (and which I was surprised to find counts Beto O’Rourke as an early member).

The book is very much a story grounded in cybersecurity — or lack there of — and the internet’s magical ability to connect oddballs, misfits, artists and technologist and ultimately provide them with the leverage to quickly weave yesterday’s “radical” weekend activities into the fabric of tomorrow’s orthodoxy. Yet, it also provides a compelling context to remember how vague and unintuitive the Internet was during much of its infancy. Take, for example, Netscape’s changing analogies during its early days.

Netscape Communications wants you to forget all the highway metaphors you've ever heard about the internet. Instead, think about an encyclopedia—one with unlimited, graphically rich pages, connections to E-mail and files, and access to Internet newsgroups and online shopping.

—Netscape Navigator, Macworld (May 1995)

I also read Neal Stephenson’s renown Snow Crash. Written in 1992, Snow Crash famously coined the phrase ‘Metaverse’ to describe Stephenson’s imagined successor to the Internet.

Indeed, well before Facebook changed it’s name to Meta, the concept had been top of mind for analysts and executives alike. More than ever, executives from Coinbase, Warner Music Group, Facebook, Bumble and beyond are eager to discuss their Metaverse strategies.

It is clear that, as William Gibson famously said, “The future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed yet.” But, like the early years of the Internet, the definition of the Metaverse remains strikingly vague and divergent.

This essay attempts to pattern match a number of trends to arrive at reductionist construction of the ‘Metaverse’.

It will start by first analyzing how Hollywood has transitioned from a culture-based entertainment economy to an imagination-based one. From there we’ll dissect the elements of the imagination economy, and how disruptive game creation platforms are enabling the amateurization of imagination.

With it, we’ll learn — given the medium is the message — that we are experiencing a paradigm shift in media, the likes of which we have not seen since the 1950s. Consequently, there are signals announcing the dawn of a new technological epoch: the Imagination Age.

Lastly, borrowing from Michelangelo, we’ll discuss the core components of the Metaverse and some exciting companies building within them. The Metaverse, in the end, will prove to be the Human Apotheosis—the imagination equivalent to Tim Urban’s knowledge-based Human Colossus — where our collective digital output approaches the infinite nature of our imagination.

Said another way, what the Internet proved to be for the Information Age, the Metaverse may prove to be for the Imagination Age.

A New Entertainment Model

“Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research.”

- Albert Einstein

Over the past decade, the Hollywood machine has undergone a fundamental reorientation as many of the tech trends of the 2010s have come to roost. The rise of mobile, streaming services and social media networks have disrupted Hollywood’s perch as the primary distributor of celebrity, culture and creativity.

Youtube, for example, disrupted the traditional studio model by creating an entertainment network that crowdsourced content creation, incentivizing individuals to become creators with compelling rewards of social capital (and less compelling economic rewards). As Rex Woodbury documents, it was a true down-with-the-gatekeeper innovation, and it’s rapid ascent demonstrates the degree by which these elements have been stifled by intellectual elitism and middlemen.

Said another way, through it’s two sided entertainment network — create & consume — Youtube enabled the ‘amateurization’ of video production. As Reggie James points out in his piece on the topic, this often leads to a meta-tension between generations. This manifested itself in forms similar to Barry Diller’s infamous quote from a 2005 interview in WIRED:

“There is not that much talent in the world. There are very few people in very few closets in very few rooms that are really talented and can’t get out.

People with talent and expertise at making entertainment products are not going to be displaced by 1,800 people coming up with their videos that they think are going to have an appeal.”

Diller was clearly wrong. In 2020, American Android device users spent an average of 23.1 hours per month on YouTube compared to 5.7 hours on Netflix, 4.3 hours on Hulu, and 2.7 hours on Amazon Prime.

Instead of of going to the movies, young people increasingly tap into culture by streaming or scrolling.

Why?

It’s not because of decreasing attention spans and deteriorating taste. Rather, two sided entertainment network more efficiently connect video with audiences that they’re sure to please. It’s that simple.

While Youtube and other social networks have begun to impose some gatekeeper like tendencies, particularly in regards to creator monetization, there is practically zero cost to uploading and publishing a video to the platform. From there, the algorithm can make better distribution decisions because it can process more information than an individual or network of individuals can.

Indeed, the belief that entertainment gatekeepers — rather than users themselves — are uniquely skilled to spot top talent and efficiently connect supply and demand has proven to be wrong way before the creation of such entertainment networks like Youtube or Tik Tok.

Publishers rejected Dr. Seuss 22 times. Dune, 23 times. Harry Potter, 12 times. Elsewhere, it took 10 years to get Squid Games greenlit.

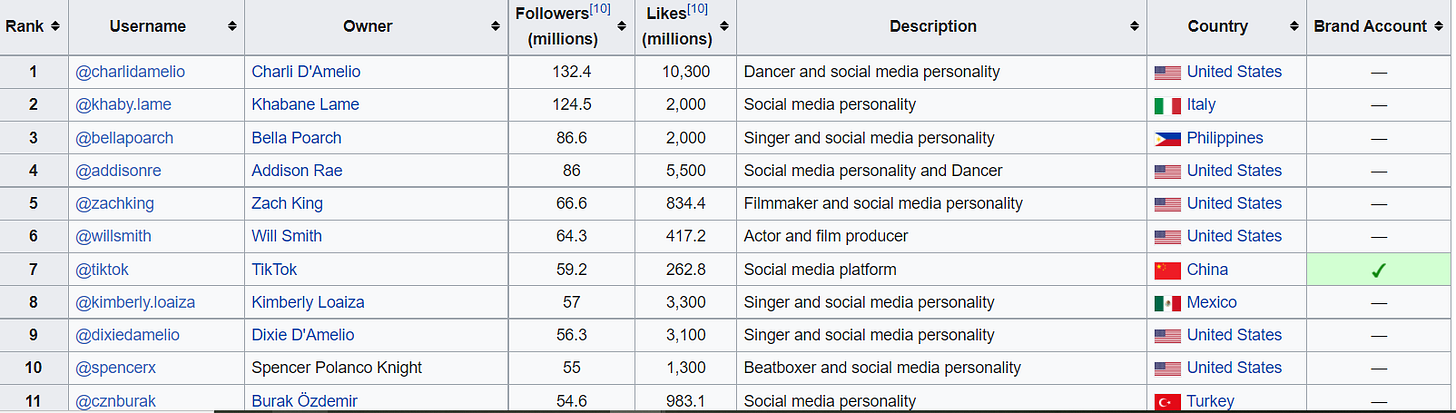

So, it’s perhaps less surprising that only one of the top ten most followed Tik Tok accounts is a ‘traditional’ celebrity (Will Smith).

And the same holds true for the top Youtube channels.

Thus, when dealing with subjective variables like entertainment, it’s hard to find empirical evidence suggesting that artificial constrains on supply ultimately best serves the consumer.

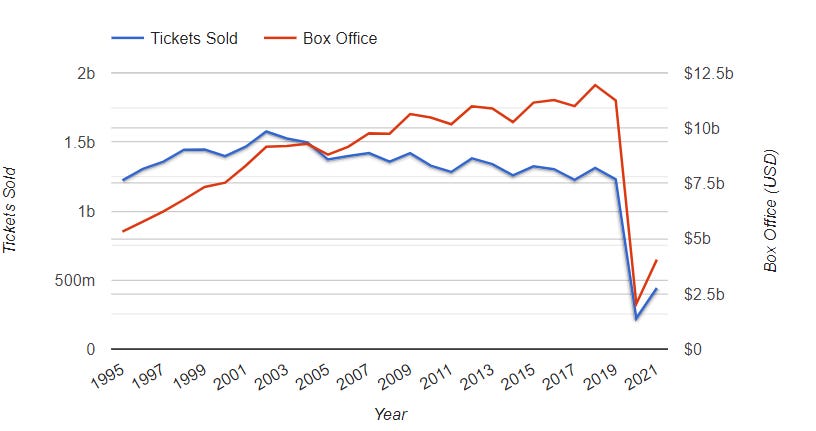

Instead, social media networks amateurized video production and enabled celebrity, culture and creativity to be community-driven and distributed, rather than hand-picked by Hollywood. With attention elsewhere, the demand for traditional box-office movie products has steadily been declining.

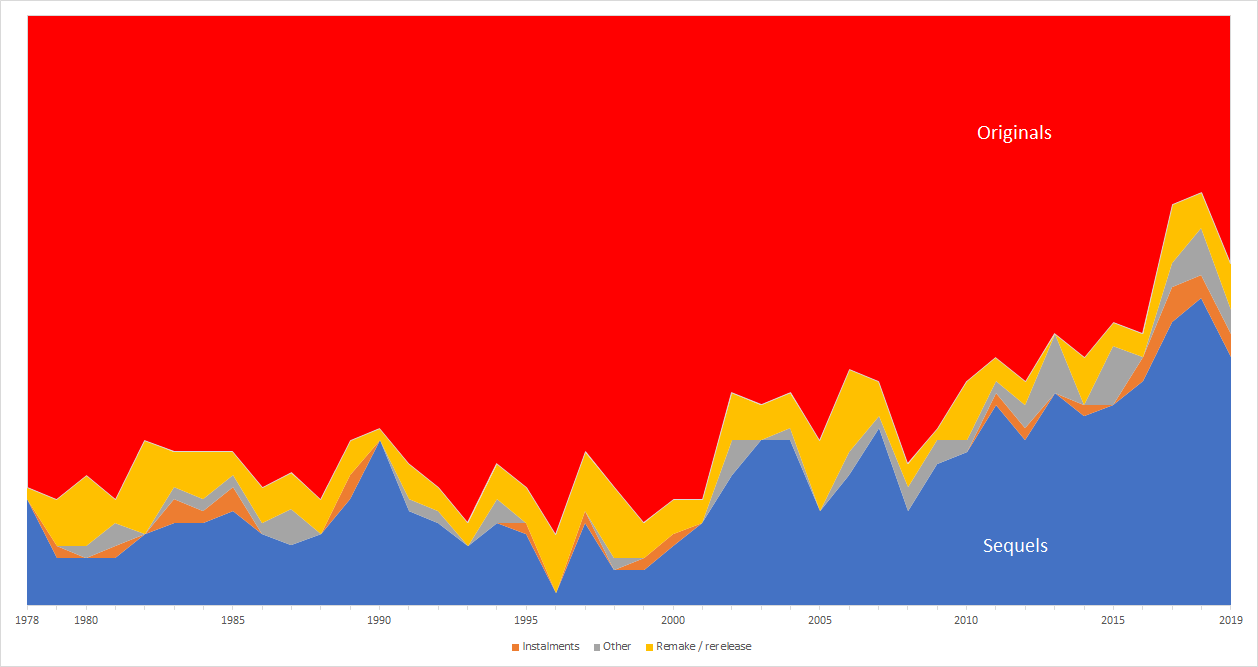

In response to this, ‘traditional’ Hollywood had to pivot. That meant more sequels and less original content (or more imagination and less culture). As such, massive franchises — like Marvel, Harry Potter, Star Wars, Game of Thrones and so on — dominate the development and production funnels across the industry.

IP has become the new oil.

Many prominent voices — such as Martin Scorsese — lament this strategy as unoriginal, formulaic and risk-averse (all adjectives that would aptly be used as antonyms for describing ‘culture’). It’s that whole meta-tension between generations thing, but this time happening within the entertainment industry.

But in this new dynamic, the content that contribute to culture rarely do so deterministically — rather social media networks use the content to create a factory of memetic objects across platforms that take on entirely different contexts (see Bird Box and Squid Game).

What individuals like Mr. Scorsese fail to realize, and what a few like Bob Iger brilliantly did, is that the economics of Hollywood no longer permit producing a product that’s main source of entertainment utility is its contribution to culture.

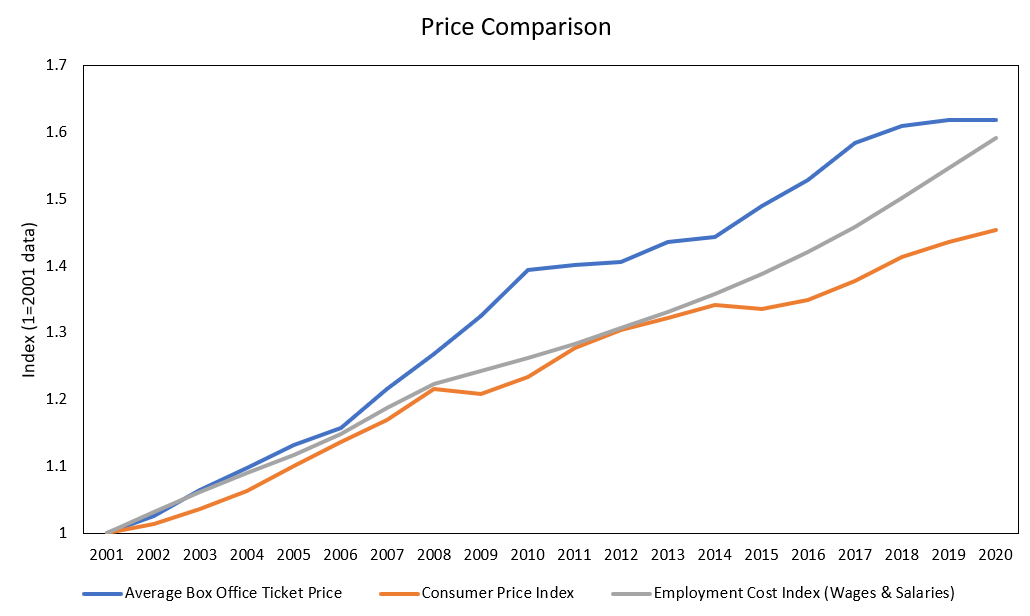

Instead, Hollywood needed to increase ticket prices to maintain box office performance amidst weakening demand, which you can see diverge significantly from wages & CPI as society entered the social media age.

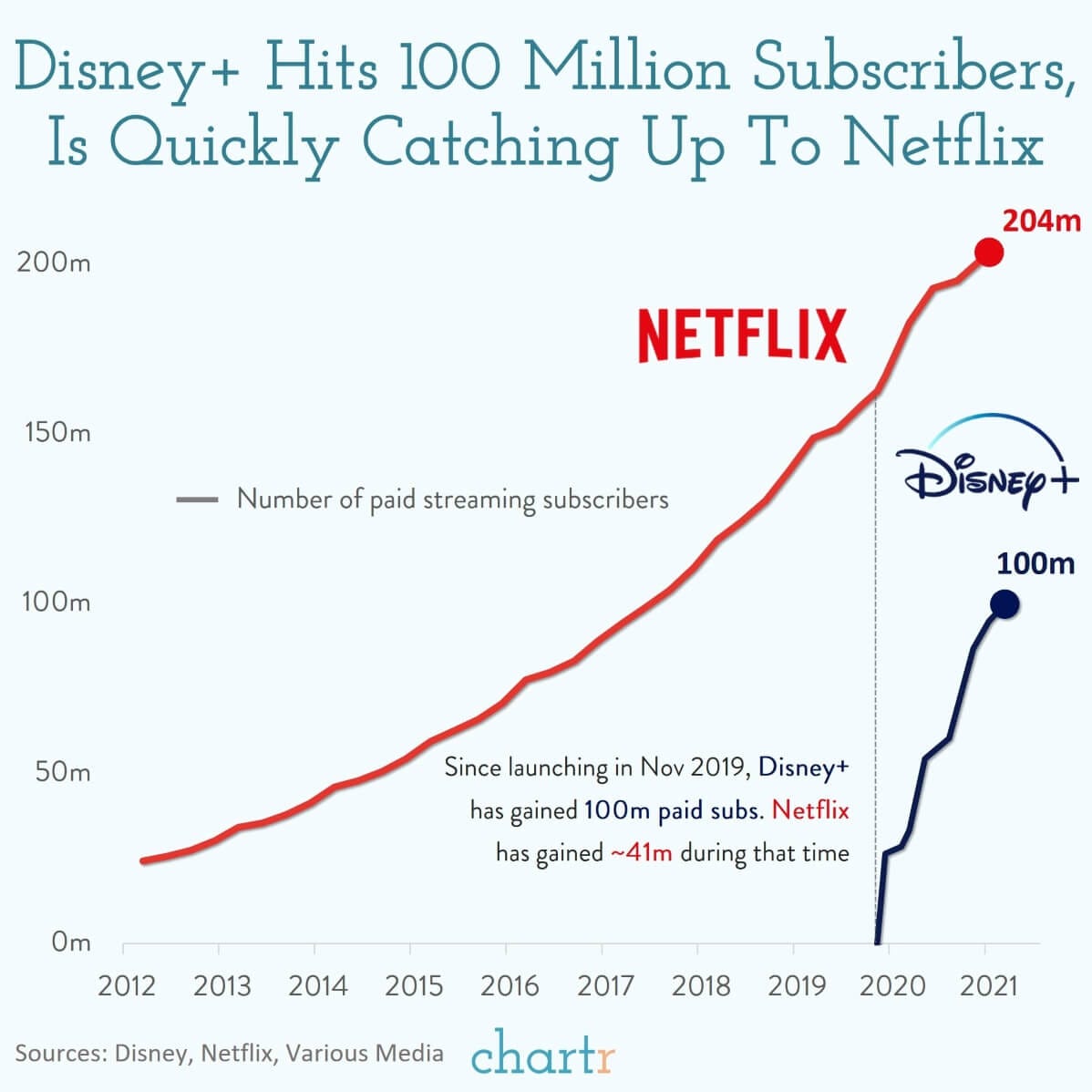

At the same time, the industry had to invest heavily in their technological infrastructure in order to compete with streaming services like Netflix. To get Disney+ off the ground, Iger noted that Disney "invested $2.6 billion to acquire the necessary technology and […] even spent $71.3 billion for the 21st Century Fox assets to beef up Disney's production capabilities and content library."

As we can see, Hollywood needed a new source of utility that could justify increases to ticket prices, compensate for the massive investment in streaming, and prove defensible to social media’s disruption via its amateurization of the three C’s: culture, celebrity and creativity. Consequently, this disruption led to content production splicing between imagination and culture, resulting in the Content K-curve.

And so, Hollywood is no longer in the culture business, but the imagination business.

The box office has become the primary port of entry into robust imaginary worlds built upon specific IP rooted in common storytelling primitives — specifically the monomyth of the Hero with a Thousand Faces which underpins the stories of Star Wars, Game of Thrones, Harry Potter, The Matrix, Dune, The Witcher, etc. — that thread across multiple individuals films to create a cohesive, meta-narrative.

Since utility comes in the form of imagination rather than culture, the sequel and spinoff — rather than being a crutch — have become innovative tools. When viewing the new Spiderman movie, consumers are paying just as much for access to the Marvel Cinematic Universe as they are for the individual narrative of Peter Parker. That’s a compelling value proposition to consumers — and one that justifies increased pricing — that increases with scale.

Meaning, the imagination economy does not suffer from the same diminishing returns that a culture economy does. Consumers want more access to imaginary worlds. In an imagination economy, surplus rather than scarcity creates value, and generally the tenth movie is better than the second movie because of the second movie, and the third movie, and so on.

As a result, these worlds are becoming increasingly omnichannel. In 2021, Marvel released four new movies as well as four new TV shows, somewhere around 70-80 hours of content. Moreover, Disney is sparing no expense on programming — its 2020 original content budget was estimated to be around $1 billion. The Mandalorian is said to have costed $15 million an episode, for instance, and a source pegs Marvel entries The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, WandaVision and Hawkeye to cost as much as $25 million per episode.

And it’s worked. Disney+’s accelerated adoption speaks to the success of this strategy and the power of the imagination economy.

With increasing scale comes better economics. As Matthew Ball notes in a conversation on Invest Like The Best, while Marvel has increased its output volume over time, they have also been able to reduce the average cost some 50% due to their ability to contract more internally for talent and production. As a result, budget appears to be somewhat constant while gross is on an upward trend.

Entertainment companies use the increasing returns to scale as a means to defend IP from other properties — both in terms of hours and dollars spent — but more importantly, from existing social media disruption that relies on crowdsourcing culture. Consequently, a new entertainment model has emerged in Hollywood.

The atomic unit is no longer the movie, but the franchise.

The Imagination Economy

The imagination economy is big business. The Harry Potter economy, for example, has grossed over $25 billion — which is about 4x more than Snapchat’s total revenue from 2015 to 2020 combined.

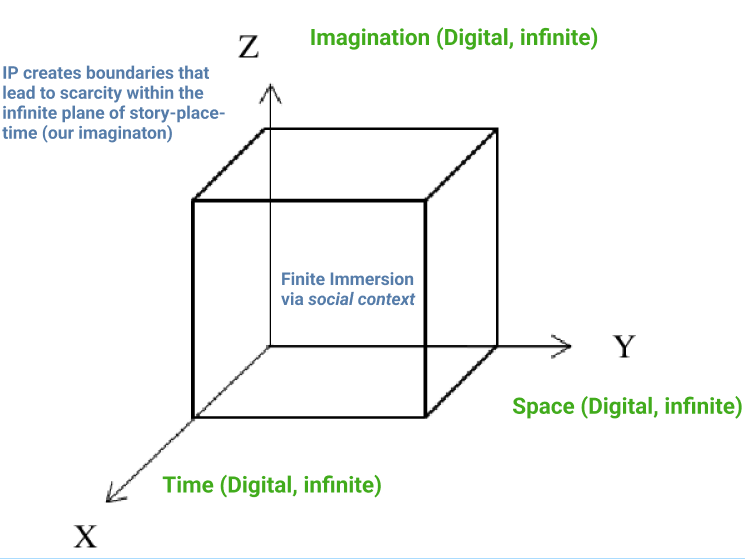

But there’s more to it than what appears on the surface. The imagination economy is composed of two types of ecosystem: open and closed, which create utility based on IP. IP provides boundaries that help reconcile the infinite (imagination) with the finite (the material).

Today, most materializations of our imagination exist as extensions of closed IP owned by corporations. This means that fans don’t have any governance, let alone direct ownership, of these characters, worlds or storylines, limiting them to being only passive consumers of the products and narratives that the corporation decides to create.

For example, Disney dictates the supply of Marvel IP, the types of formats it can be produced within (movies, shows, toys, accessories, theme park), where it can be distributed and how it is monetized. Ownership is at the largest unit (the franchise) and few rather than many can be creators — such as actors, directors, etc. — that contribute to the imaginary world.

Conversely, the open ecosystem is distributed and deals with two types of open-source IP primitives. The first is public domain IP — topics, events, mythos, histories and narratives that live in the public domain, meaning they are completely decentralized and composable. The Titanic, for example, has been produced in a number of different formats — whether it be a massively popular movie, a lego set, or tens of different museums around the world — that are independent of each other or a centralized body that owns the ‘Titantic universe’.

The second IP primitive is a hybrid: it creates derivative experiences and products using an open-closed imagination stack that creates utility based on context. For example, a Lord of The Rings tour guide in New Zealand stacks open IP (New Zealand) with private IP (Lord of the Rings) to create an imagination product. Ownership is distributed to the atomic unit (the tour), production, monetization and governance are composable. Here, anyone can be a creator given a compelling enough skillset or wedge.

While the imagination economy has transformed the entertainment industry, there are a number of signals that suggest that consumers continue to be underserved. Many ‘hybrid products’ are created to capture this demand.

Set-Jetters

Hoards of consumers — coined ‘Set-Jetters’ — travel the world visiting the places where their favorite shows and movies were filmed. In the process, rich open imagination economies have emerged across geographies and franchises.

For example, Harry Potter is said to have contributed some £4bn to the UK economy as of 2016. Moreover, Screen NI, a taxpayer-funded agency that helped finance the Game of Thrones, estimated that spending on goods and services associated with the show added £251 million ($328 million) to the national economy since the show began filming in the countryside and craggy coast of County Antrim. In fact, the agency suggests that 350,000 people come to Northern Ireland every year just for Game of Thrones!

What’s fascinating is that consumers opt for these services rather than visiting Wizarding World of Harry Potter or other private theme parks that are near replicas of the sets seen on screen. Indeed, between 2013 and 2015, Comcast spent $2 billion on theme park capital expenditures to build such attractions.

Instead, fans like Thelma Okocha, a 29-year-old business intelligence developer who works in New York, would rather travel across the world to experience the imaginary worlds of their favorite stories. For these fans, the stories exist in a network of physical places that are completely distributed from the IP owners, and accessing them can only be achieved via services that combine open and closed IP primitives (more on this below).

"That's where Melisandre gave birth to that demon shadow that killed Renly Baratheon," Okocha says pointing to a cave, "I can't believe I'm here."

That last sentence is crucial as it demonstrates the importance of immersion as a source of utility in the imagination economy. While theme parks benefit from near perfect set replication, actors in character and insane production quality, the product ultimately proves to be inferior as it lacks social context.

Rather, the social context exists as coordinates that you can access by combining Game of Thrones canon (closed IP) with a specific physical location (open IP). In other words, the experience has value because it is defined relative to a social context, which creates scarcity as it might only exist in that context. More, it requires you to exist in two separate planes at once — the finite physical world (i.e. Northern Ireland) and the infinite world of your imagination (Game of Thrones). Thus, the coordinates define the boundaries within the infinite three-dimensional plane of imagination-place-time.

If you’ve never watched Game of Thrones, visiting the cave where Melisandre gave birth to the demon shadow has no additional value compared to any other cave because there is no vector within the imagination-axis. But for the millions of individuals who are privy to this context, this is no ordinary cave, but a defined portal.

By visiting it, fans are given the most tangible, immersive materialization of their favorite imaginary world.

“Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?”

- Dumbledore

Set-jetting reveals the potential value creation unlocked via distributed networks that are better tooled to create products that maximize immersion, even when grossly undercapitalized. A local tour guide in Northern Ireland very likely provides more value to consumers than an entire theme park potentially could.

Set-jetting is one such example, yet many others exist.

The Quidditch Fork

Since 2005, Quiddith — the fictitious sport from Harry Potter played by wizards on broomsticks — adaptation has spread to more than 200 college, community and professional teams across the U.S., involving more than 4,000 players.

Towns like League City, Texas and Columbia, South Carolina have hosted two-day tournament that attracted an estimated 5,000 people each day.

Interestingly, the Quidditch governance body (US Quidditch, a 501(c)(3) organization) have begun using their influence for political means. In response to Shawnee, West Virginia’s bid to host the 2024 event, US Quidditch wrote that it would no longer consider bids from West Virginia because of the state’s recently passed bill that the organization deems as discriminatory to the transgender community. In response, Charleston, West Virginia major Shuler Goodwin said the loss of the tournament would lead to $1.5 million to $2 million in economic loss for local businesses.

Clearly, US Quidditch has built an organization with some weight to it, but has set on a course completely independent of the original Harry Potter IP that serves as its epicenter.

Essentially, Quidditch offers an analog way to permissionlessly institutionalize and decentralize ownership of Harry Potter. To that end, if you squint your eyes, US Quidditch sorta operates like an offline DAO.

Think about it. A community was formed around a collective fandom of Harry Potter. This community desired a specific product (Quidditch) that lived in their imagination and which they had access to in other formats, but clearly their needs were underserved. For this market, product-market fit meant an offline, physical Quidditch league — not figurines, video games or 30-second snippet scenes of actors playing Quidditch in a two-hour movie.

So, this community forked the source code and raised capital (via donations) to build the product. The community — now organization — operates independent of Warner Brothers and is building towards a future — as evident by their stance on transgenderism — that is independent of, and in fact different than, the source code.

More, these individuals interact with the IP in material and social ways, a richer concept than pure physical possession. Possession here is a freemium right — you theoretically don’t even need to be a Harry Potter fan to even participate — as individuals gain utility in the social context they create based on the IP, which is uniquely governed by their league. Ownership is a function of an individuals proof of imagination — the more you contribute to the Quidditch as a player and/or governor the more social capital you hold in the organization.

Interestingly, there is no mention of Harry Potter in US Quidditch’s ‘What is Quidditch?’ website explainer.

Quidditch is a fast-paced, contact sport created in 2005 and played in over 39 countries. A quidditch team consists of up to 21 athletes with seven players per team on the field at any one time. Each player must keep a broom between their legs at all time. Points are scored by throwing a volleyball (the quaffle) through any of three hoops fixed at either end of the field, while dodgeballs (the bludger) are used to ‘knock out’ players temporarily. The snitch is the ball that must be caught to end the game.

Quidditch simply started as a number of individuals possessing brooms but created utility within the contexts of Harry Potter IP. In the process, they’ve tinkered the Harry Potter IP to create an entire sports league. Now, the interesting question becomes which of the two — Warner Brothers or US Quidditch — owns and operates the real Quidditch?

Amateurization of Imagination

Set-jetting, quidditch, and more serve as signals for the massive potential of the imagination economy if made composable, distributed and community-driven.

Yet, Hollywood still operates as a gatekeeper, albeit in a different zip code: instead of centralizing and controlling the production of culture-based entertainment, they’ve done the same with imagination. A few sources of IP — Marvel, Star Wars, Game of Thrones, Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings — dominate the imagination economy, and the increasing returns to scale means that executives choose to allocate capital to expand these worlds via sequels and spinoffs. In this tactic, scale and professionalization become the moat.

However, the strategy is reflexive and suffers from the same flawed calculus that occurred a decade prior.

Let’s revisit Barry Diller’s quote:

“There is not that much talent in the world. There are very few people in very few closets in very few rooms that are really talented and can’t get out.

People with talent and expertise at making entertainment products are not going to be displaced by 1,800 people coming up with their videos that they think are going to have an appeal.”

The thinking today echoes many of the past: there is not that much scalable IP in the world, nor are there thousands of talented individuals that can create enough content or products that can disrupt, or contribute to, a Marvel Cinematic Universe or Game of Thrones.

But like Youtube did previously, Roblox is proving that Hollywood vastly miscalculates the talent pool that can create compelling imagination products given the proper tooling.

For those who are unfamiliar, Roblox is a game creation platform that enables users to create content such as skins, avatars, games and experiences overlaying community-driven, and owned, IP.

Instead of 1,800 or so talented individuals, Roblox currently has 9.5 million community developers. In Q2 2020, developers made over $129 million, an 8x increase since the beginning of 2018.

More, of the 40 million games created to date, 5,000 have had more than 1 million plays, and 20 have had more than 1 billion plays. Every month, roughly a quarter of Roblox’s top 100 games are new.

From September 2019 – September 2020, over 960,000 community developers earned virtual currency on the platform for their contribution to Roblox’s various imaginary worlds.

This can be for as small of a contribution as creating a pair of pants that other users can purchase for their avatar. In fact, 99.47% of community developers make less than $1,000 per year on Roblox, and only a fraction (<1%) actually exchange their Robux for US Dollars.

Meaning, the vast majority of users are contributing – and liquifying their imagination – to the decentralized imagination economy in order to participate in it further. They do so by exchanging Robux for access to premium games or to purchase identity objects (like avatars and skins) that serve as a status mechanism to signal a user’s ‘proof of imagination'.

Over the past few years, gaming has evolved from semi-interactive content to become fully-fledged social platforms. As I wrote about in eCommerce is Dead, it Just Doesn't Know it Yet, kids under 13 spend more time on Roblox than on YouTube, Netflix and Facebook combined.

Yet, there is a clear delineation that separates social gaming platforms from social entertainment platforms like Youtube, Tik Tok and to a lesser extent Instagram.

These social media companies disrupted a culture-based entertainment industry by building a tremendous network that efficiently matched supply and demand via algorithms rather gatekeepers.

Moreover, they integrated distribution with certain tooling that allow users to create an extension of their physical self and consume content with clear nexus to the physical world — both in terms of highly relevant, reality-grounded subject matter and their video-based medium that captures the offline self rather than creating a novel online one.

Roblox, on the other hand, offers the tooling to create an imaginary self — a digital identity that is completely dissociated from your physical one — and interact with content by immersing in a world with limited-to-no nexus to the physical one. So, it offers completely novel form of entertainment, one that is rooted in the current imagination-based paradigm of the entertainment industry, yet follows a similar path of disruption as the social media networks before it.

Roblox is an imagination factory akin to Disney, except it crowdsources it’s imagination production. Roblox games rely on roleplaying, like Marvel and Game of Thrones, yet do a superior job transmuting the subjectivity of imagination into an immersive, material experience by enabling more creators to build more products and experiences.

As Chris Misner, head of Roblox International, puts it:

“We’re not a game; we’re a platform for creativity and play. We provide tools and support for people to build what their imagination wants. The only limit is their imagination.”

Roblox is leading the amateurization of imagination.

While the content lacks the refinement and scope of a Marvel, the platform offers utility that entertainment properties cannot. Specifically, Roblox provides a social context and virtual place that allows the dimensions of story-place-time to exist on a singular, unified plane — one where users actively participate and are given the agency of watch, play and create.

It is pure disruptive innovation. Roblox makes expensive and sophisticated imagination products accessible and more affordable to a broader market. Framing it within Clayton Christensen's "Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits", Roblox modularizes imagination production by making attributes, items, avatars, experiences and worlds composable, and integrates it with distribution and monetization. Conversely, incumbents integrate imagination production and modularized distribution (linear, box office, accessories, movies, etc.).

More, like US Quidditch, developers on Roblox are forking closed IP to create derivative products that are undersupplied, offer greater product-market fit and/or novel adaptations.

Type in any of your favorite IP — Harry Potter, MCU, Game Of Thrones, etc. — and you will find dozens, if not hundreds, of unique virtual containers that offer both immersive access as well as unique storylines that contribute to, and sometimes fork, the original canon. A Harry Potter knockoff called Ro-Wizard has 35.2M+ visitors, The World of Marvel 3M+. Following Squid Games launch, the platform’s trending section was littered with titles like “Squid Game” and “Red Light Green Light,” with 8.3 million visits and 27.6 million visits, respectively.

All of these mini-games are unlicensed and unaffiliated, but persist nonetheless. By crowdsourcing production via light-weight tooling, fans of these worlds receive the benefits of supply surplus (more access) that also prove to be more immersive and more social than any other imagination product. With it, sandbox game platforms like Roblox allows immersion to happen at scale.

The Medium is the Message

The world of reality has its limits; the world of imagination is boundless.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Marshall McLuhan, The Canadian Philosopher whose work is a cornerstone of media theory, once famously said “the medium is the message.”

By this, McLuhan meant that the forms used to communicate information have a significant impact on the messages they deliver, and ultimately the medium has a greater effect on society than the content it carries.

Today, we are experiencing a medium change.

For the first time since the near universal adoption of the television in the 1950s, a generation of consumers no longer consider video as the primary medium by which they consume entertainment.

According to Deloitte’s 2021 Digital Media Trends survey, video games are their No. 1 entertainment activity for Gen Z consumers in the U.S. — watching TV or movies at home comes in fifth (Only 10% of Gen Z respondents!). For every other age group, watching TV or movies remains the top pick, including among millennials (18%), Gen Xers (29%) and boomers (39%).

With this, video gives way to gaming, the story gives way to the world, and we move on a continuous progression to tap into the subjectivity of our imagination and liquify it into novel digital formats. Immersion is happening at scale.

This is the imagination age.

Initially coined by Rita J. King, the imagination age is a theoretical period beyond the information age where creativity and imagination will become the primary drivers of economic value. This is driven by technological trends like virtual reality and the rise of digital platforms like Tik Tok and Roblox that amateurize and democratize culture, creativity and imagination, all of which increase demand for user-generated content. It is also driven by automation, which will take away a lot of monotonous and routine jobs, leaving more higher-ordered and creative jobs.

What the Internet is for the information age, the Metaverse will be for the imagination age.

The Metaverse: Imagination Made Liquid

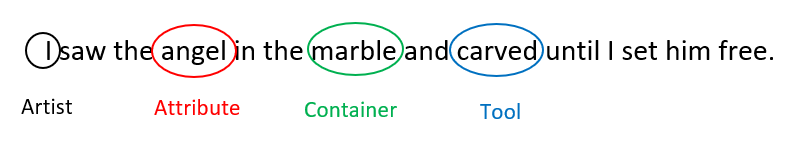

Michelangelo was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect and poet of the High Renaissance — a true multi-hyphenated individual that would make many Hollywood agents salivate. Beyond his incredibly artistic talents, perhaps his greatest skill was his ability to grasp the infinite elements of his imagination and shape them in the finite world.

As he put it:

I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

While Matthew Ball’s primer on the Metaverse has become canon (and rightfully so), I believe Michelangelo’s framework outlines the features that will serve as the nucleus of the Metaverse.

In it’s simplest form, the Metaverse has four core elements.

The Attribute

The Container

The Tool

The Artist

The Attribute

Attributes are IP that are programmable and ownable at the atomic unit. The sum of your attributes creates your digital identity. These can be in more ‘tangible’ forms — such as virtual cosmetic items that outfit your avatar or NFTs that you collect — and more ‘intangible’ forms like your credentials, social graph and transaction data.

Because these attributes are programmable and open, any developer can build on top of them. And because NFTs are user-portable, programmable attributes can take on new utility across the totality of our digital world.

Innovation is already happening here. Companies such as DressX, Customuse and RTFKT allow anyone to design virtual apparel for avatars in games and AR experience.

Moreover, Wolf3D creates personal 3D avatars of people from a single selfie for games and virtual worlds. Most importantly, the company is building a cross-game avatar platform that makes it easy for users to navigate between many virtual experiences while keeping their identity consistent.

Others focused on proof of attendance (poap) to proof of early adoption (sound.xyz). are creating attributes via tokens that link to a history of achievements and activity — whether it be early adoption, attendance or contribution.

Attributes are persistent and portable across containers. As we will see, every attribute is social context in potentia, and NFTs represent unspecified rights in that context.

The Container

Containers are virtual portals that render attributes based on defined creative formats and standards. Containers, like attributes, can be platform agnostic. For example, Oorbit is a platform that enables PORTS — or AAA games and interactive virtual worlds — that can be shared and accessed on web browsers, mobile devices, as well as inside Facebook, Twitter, and more.

Containers differentiate based on how they render and utilize attributes. Roblox and Fortnite can both be thought of as imperfect containers. But in a modular, Web3 Metaverse, attributes (say owning a golden sword and having fiery red hair) are portable and will persist regardless of whether I am on Roblox or Fortnite, although the creative rendering of the attributes will differ.

In addition, certain containers may provide more utility to certain attributes over another. For example, Fortnite may have a partnership with Marvel, and so ownership of a Iron Man skin provides my avatar with superior strength than the same skin would in the Roblox container.

As such, the success of a container is ultimately a function of its ability to attract artists and developers to build finite virtual places and experiences within the container that maximize the utility of certain communities attributes. This can be a game, like the Iron Man example, that enhances the value of an attribute within a specific context, or a place, like a FWB clubhouse, for certain communities to congregate based on favorable rendering conditions to the attributes that connect them.

As a result, instead of a few such global scarcity-creating social contexts (like Harry Potter or Marvel or Game of Thrones), any combination of attribute(s) and container can create its own scarcity-based social context.

The next animated Game of Thrones may be filmed in a specific container, and fans — defined by owning certain attributes — will be able to immerse themselves in the imaginary world on a unified plane of story-place-time. Similarly, Harry Potter fans — again, defined by owning certain attributes — will be able to play quidditch in a container that optimizes its rendering based on the physics of the gameplay.

Spatial is a container that powers spaces that bring people together. Spatial makes it easy to create online galleries where people could view NFT art or even start the process of buying an image on display. The company brands itself as a “metaverse for cultural events” such as NFT exhibitions, brand experiences, and conferences.

Some attributes in Spatial are portable (like the NFT paintings below), yet some are not (like my avatar).

Ideally, for a synchronous Metaverse that allows true ownership and composability of digital identity and imagination, containers should be minimally extractive — meaning the container should optimize for the maximum amount of user-owned attributes within a context. Other objects — like the clouds, surrounding mountains and stage — can exist as intrinsic to the container, but only as much as to define the aesthetics of the virtual place rather than it’s potential social context.

The Tools

Tooling on the Metaverse will be a spectrum. On one end, game engines like Unity and Unreal Engine have already democratized and enabled more complex gaming ecosystems and 3D workflows. On the other, the rise of low-code/no-code tooling will enable a proliferation of new developers to create simpler objects, artifacts and experiences to power the Metaverse imagination economy. Indeed, Microsoft expects 500 million apps to be built in the next five years—which is more than what has been built in the past 40 years. Of those 500 million, 450 million are expected to be built with low code / no code tools.

As Packy McCormick recently observed, “one of the big innovations of web3 is that there’s a shared backend and database on top of which anyone who knows how to code can build unique user experiences. In the ideal state, it could actually cause a reallocation of engineering resources globally to focus more on creating differentiated front-ends and less on re-building the same backend infrastructure and databases over and over again”.

The coinciding increase of developers, low code tooling and reallocation of engineering resources from backend to frontend has the potential to create supply dynamics that can meet the incredible demand of the Metaverse imagination economy.

Again, innovation is already underway. One such example is Anything World, which teamed up with Atlantic Records artist Pink Sweat$ to create a new type of interactive music experience that travels the user through an animated Pink Sweat$ Pink Planet (container) when connected with Spotify (attribute of fandom). This is a perfect example of attribute-container social context.

More exist. InWorld is a developer platform for creating AI-powered virtual characters to populate immersive realities including the metaverse, VR/AR, games, and virtual worlds. DNABlock offers software platforms for companies to create their own virtual influencers and digital avatars. With their AI-powered animation platform, Aquifer gives content creators with no technical animation skills the power to produce cinematic-quality animated content in minutes. Wonder Dynamics aims to make “blockbuster-level” visual effects achievable by living-room-level creators using AI and cloud services. Skeptics might be comforted by the presence of Steven Spielberg and Joe Russo on its advisory board.

But, ultimately, the future tooling will look more like Replit. Again, as Packy writes, “just as teenagers can build, host, and sell games and items all within Roblox, teens can build, host, and sell software in Replit. Unlike Roblox, though, Replit is plugged into the entire internet”.

But instead of, or in addition to, the Internet, these future tools will plug into the entirety of the ‘Metaverse’.

The Artist

As consumers look for active participation in online ecosystems and communities, the act of creation will become easier than ever. Modular, off-the-shelf tooling will allow anyone to create imaginative attributes or container-based services.

The automation of core tasks for creation will become essential for filling the endless demand for new content as new platforms, ecosystems and companies are created. We have already seen this play out in Roblox, where you can become one of the star creators of Roblox games and worlds, making millions even before graduating high school.

I imagine future talent marketplaces akin to Braintrust will allow users to review and rate developers — and potentially create a new artist celebrity class of developers akin to Beeple. There may perhaps be the Metaverse equivalent of a Hattori Hanzo, a master digital sword smith. Or a Garrick Olivander that proves to be the best digital wandmaker. But importantly, while these developers may create products that provide social status, the permissonless and composable nature of the Metaverse means that other developers may be attracted to build subsequent services and experiences that eventually grant them intrinsic value — in the form of superior gameplay, access to certain content or places, tokengated commerce, and so on.

More, in Web3, all of the contributors can earn income from these services: the IP owners (such as Warner Brothers) that grant the products immutable authenticity; the developer who leveraged the IP to create a product (such as Garrick Olivander wands); and the developer who built a subsequent service or experience to create a attribute-container social context (such as a dueling tournament for owners of Garrick Olivander wand holders). Each component lives on the blockchain and value flows to creators frictionlessly and instantaneously.

The future is a promising blank canvas. A report by the World Economic Forum finds that almost 65% of the jobs elementary school students will be doing in the future do not even exist yet, and according to the Institute for the Future 85% of today’s college students will have jobs in just 11 years that don’t currently exist.

With the epochal shift to an imagination age, communities will reward highly imaginative individuals and hire the best creatives to materialize their neurons into a near infinite formats. I believe many of the jobs created over the next decade will do to just exactly that.

Closing Thoughts

The Metaverse is, in its simplest form, a context where the dimensions of imagination-space-time exist on a unified, digital plane. Anyone can create anything within this plane that they can visit by knowing it's (x, y, z) coordinates. The Metaverse will transform the imagination economy by enabling a digital social context.

For this to occur, certain stipulations must persist. The four components of the Metaverse must be unbundled from any specific platform, and ultimately be modular so that imagination synchronously flows across the entire Metaverse, rather than be contained in the walled ecosystems that we see today.

This will be no easy feat and will most likely require a common Metaverse protocol similar to SMTP and HTTPS to permit a standardized unit of data to represent attributes that are also interoperable across the various different rendering formats of each unique container. NFTs and blockchain technology enable the former, I am less educated on the computer science needed for the latter.

Similar to how social media created this Cambrian explosion of user generated content, the Metaverse will enable user generated imagination that adds to existing IP, creates new immersive experiences, products and economies, and thereby liquify the infinity of our imagination. It must be ownable at the atomic unit, portable across platforms and permissionless.

At the same time, it’s important to temper our expectations with pragmatism. Bill Gurley recently expressed a perspective that at first may be construed as pessimistic, but should rather be heeded as a much needed point of dissent to help level-set our current ‘Metaverse’ mania.

There's a version of what people call the metaverse, where we all jump into this 3D virtual world, with some representation of ourselves that is a avatar that we've all adorned. Our big learning was that there's a certain type of person that really enjoys doing that. […] Kids, they role play all the time, even before the internet. They do dress up, and they build little spaces and tents, and those kind of things. And so, it's very common for a child to want to do that.

As we get older, it's less and less common to actually do that. And there's a question. And I think, once again, Phillip has some ideas on like the types of humans that really get a lot of psychological benefit and dopamine out of that type of escapism. It may be actually a small fraction of adults

This begs a relatively important existential question: why do we lose our childish imagination as we age? Is this driven intrinsically, by rules of biology similar to what happens to our cells and muscles? Or is it extrinsic, some combination of inevitable pessimism that comes with adulthood and the constant sobering winds of ‘real life’?

Perhaps, it’s neither. Perhaps its simply a function of incentives. Perhaps, as we age, we no longer keep our heads in the clouds because the incentives rewarding that behavior just simply hasn’t been significant enough. There comes a point in time where you have bills to pay and mouths to feed.

Yet, I think that’s changing.

In a April 2016 blog post, Amjad Masad, the founder and CEO of Replit, published a tremendous realization about entrepreneurship that beautifully echoes the perspective of this post. I’ll end with this.

I view entrepreneurship as means of reconciling the infinite and finite. You venture into your imagination, gather knowledge, and dream about a better world. But you have to bring some of that back to earth. You take a step -- no matter how small -- towards your imagined world in the real world.

[…]

I see this as the perfect framework for the work we do in technology. There is always a tension between what is and what could be.

I believe the Metaverse is simply the next chapter to this beautiful story of technology and entrepreneurship. But one in a new age where the incentives finally align to reward the dreamers.