Social Retail: Immersion & Serendipity

The Socialization Spectrum, Passive vs. Active Socialization & The Great Bifurcation

I recently moved from Los Angeles to Williamsburg. As I acquaint myself to my new neighborhood, I find myself exploring local retail stores, often with no intention to purchase anything.

In fact, I type these words from a coffee shop. The store brims with shoppers who linger, many for hours, with strangers at communal tables as they sip their cappuccinos and review code, manage eCommerce stores, or in my case, write a Substack blog post. Occasionally words are shared, many times not. Other times, inevitably, eye contact is made between various individuals, maybe followed by a gentle smile. Sometimes it’s awkward, sometimes it’s affirming.

But day by day, we continue to opt in to this social behavior. I choose to write this post in a busy coffee shop surrounded by strangers rather than by myself in my apartment.

which begs the question, why? This essay will seek to answer this question.

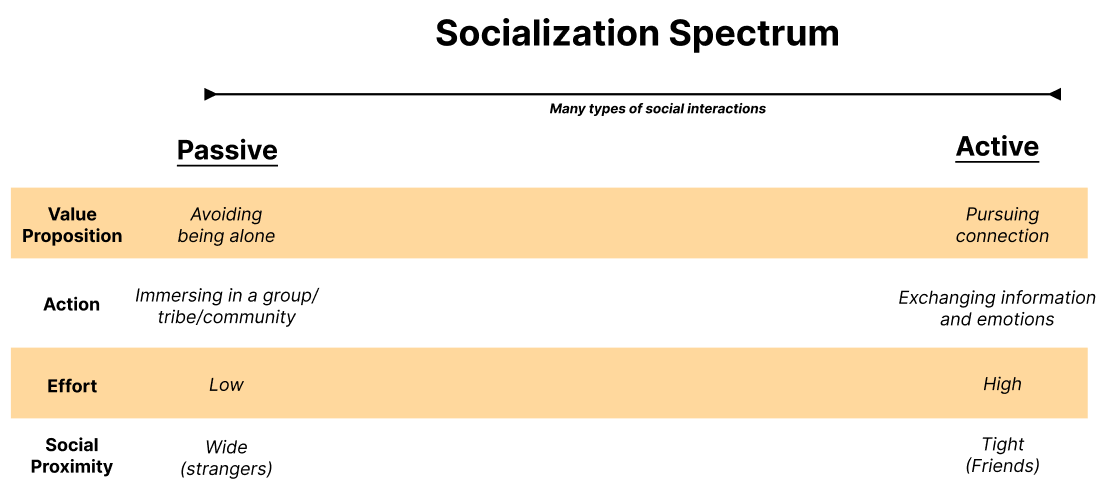

The Socialization Spectrum

Humans are social creatures by nature.

Even when engaging in our own isolated professional echo chambers, humans search out settings where they can be around other people. Importantly, by being around other people, we can engage in innate, almost primal, micro social interactions that provide us with emotional utility.

This reveals a fundamental truth that, I believe, must be applied when considering any human-centric application: People don’t like feeling alone.

But what does it mean to be social?

As I sit in this coffee shop, I haven’t socialized in the traditional sense. Nonetheless, I feel something. This is a good feeling: it is warm, comforting, affirmative. It is sense of belonging to a group of people, a community if you will, that also enables easy access to more active socialization.

We take on risk to achieve this feeling.

We are willing to take on the social cost of moments of uncomfortableness — strange eye contact with a stranger, being disrupted, someone engaging you in conversation when you aren’t interested — in exchange for avoiding the feeling of loneliness.

Indeed, this is a form of socialization, although in a more subtle manner.

In fact, I believe that there are many types of socialization that exist on a spectrum ranging from passive to active interactions.

Passive socialization is achieved through immersing oneself in a group, tribe or community. We do so to avoid being alone and gain value from the passive social interactions that result from such immersion. This is the coffee shop example: the effort is much lower — to engage in this socialization often doesn't even require an individual saying a word — and we are willing to engage in these social interactions with a wide social proximity of individuals, many of which are strangers.

Conversely, on the other end of the spectrum, people engage in active socialization by pursuing connection with each other. People gain value from the feeling they receive when exchanging information and emotions with other people, and these connections often channel in the form of a conversation. This requires much more effort — talking requires a lot more mental and physical energy than sitting silently. As such, we usually demand a tighter social proximity to engage in such behavior. If too wide a social proximity, the cost of uncomfortableness in engaging in active social interactions may be too high and prohibit such social interactions from occurring. Think, for example, your likelihood to have conversations at a networking event that you know no one versus knowing many people, or the difference in your comfortableness sitting down next to a stranger at a coffee shop (passive social interaction) versus conversating with them (active social interaction).

What I find fascinating, however, is observing where these social interactions occur. Indeed, as I have noticed at my coffee shop, and witnessing the line snaking the block at the Glossier store nearby, commerce — and retail in particular — enables much of the social interaction that we enjoy on a daily basis.

While these interactions may be more passive in nature, they provide us with tremendous value as we avoid feeling lonely and immerse ourselves in a context where we can find belonging with very little effort and cost.

Importantly, passive social interactions facilitates serendipity, which in turn, facilitates active social interaction. The more we are willing to immerse, the more we are bound to collide and connect.

While the majority of social interaction use cases that occur at the coffee shop are passive, the social collision of likeminded individuals that the retailer attracts leads to active social interactions that both greatly benefit the consumer, and indirectly benefit the retailer.

For example, a girl behind me in line at the coffee shop was, based on her tennis whites and Wilson racket, on her way to play tennis. An active player myself, I started chatting with her and had a pleasant conversation that led to us exchanging information and making plans to play at a later date.

Now imagine that we become good friends. I, as a consumer, will attribute the source of our friendship to the coffee shop, which will both improve my loyalty (and retention) and my likelihood to recommend it to other (higher NPS). This is tremendous value that the retailer serviced at zero cost. It is a form of leverage on the social dimension of shopping.

But what’s important to that fidelity of such social collision is (1) identity and (2) the medium.

Identity

When entering the coffee shop, individuals must be able to express their real identities. With their identity, they can then see and be seen and create the element of mutual reciprocity: fitting in and standing out. This is what allows me to recognize a fellow tennis player and thus transition from passive social interactions to active social interactions. To establish the trust that is required for both, it is essential that individuals can quickly diligence strangers and use their identity and behavior to arrive to a judgement of similarity, comfort and trust.

In the physical world, we often rely on indicators like physical traits, fashion, facial expressions, body language, behavior (are they working on a laptop or reading a book or eating a banana looking into space?) to make these judgements. Without identity, these indicators are invisible and we cannot attribute our judgement and assign reputation to specific individuals in a permanent and persistent manner. In those conditions, there is much less trust and much higher costs to both passive and active socialization.

The Medium

Secondly, it is important that I can conversate with a stranger easily and that the setting has a frictionless medium of social exchange. This means that the context must allow, and in fact nurture, talking and conversating. The cost of initiating a conversation is much lower in a setting where there are active conversations ongoing amongst pockets of individuals as the sense of uncomfortableness is lower for both parties.

Additionally, this social cost also depends on the user’s implicit trust in the retailer as an aggregator of people. Meaning, there is a lower cost — in the form of uncomfortableness — for me to initiate conversation and for the recipient to engage in conversation in a setting that you trust attracts individuals that have similar interests as your own and with whom you have a high likelihood to get along with. In settings of strangers, like retail, the host of these social interactions takes on an even more important role in this regard.

In this vein, the job of the retailer is similar to that of a traditional social network that applies the axiom “come for the tool, stay for the network”. The product is a tool that gets customers in the door, and the retailer then acts as an exchange of social interactions that distributes a supply of passive interactions that create a sense of immersion and satisfies our desire to avoid feeling lonely.

Great retailers further differentiate themselves by creating a brand that speaks to a specific persona of people who have similar problems, interests and/or life experiences, thereby creating a tighter proximity amongst strangers and limiting the cost of uncomfortableness. This increases the chance of serendipity — both running into friends and making new ones — that facilitate active social interactions and maximizes the social utility we gain from engaging in active social interactions on their platform. This attracts other people and creates network effects.

Anecdotally, I come for the coffee, but stay for the social interaction. More specifically, I come for the coffee, stay for the immersion, and come back for the serendipity.

In a world of branded quasi-commodity products like coffee with little barriers to entry, the social interaction — or atmosphere of the store’s community — is ultimately what differentiates a brand and creates defensibility.

I experienced this first hand.

The Cigar Lounge

Growing up, I worked at my father’s retail store. It is called Tinderbox. Tinderbox sells cigars, pipes & pipe tobacco and various accessories.

While working at his store, I made few observations.

His store was a community of unlikely friends from all walks of life,

That formed connection and a sense of belonging due to their shared interests in cigars,

And frequented the store for the social interaction just as much as the commerce.

My dad would always tell me, “Sam, we don’t sell a product, we sell a feeling.” When a customer would leave the store with a smile on their face, it wasn’t because they received a discount code or special deal. It was because they had a great social interaction. The social interaction could have been a passive one, like quietly immersing oneself in a group of fellow cigar lovers, but nonetheless, that social interaction is what influenced how customers felt when they shopped at our store.

These interactions often occurred amongst strangers. Sometimes conversations indexed on topics regarding cigars, many times they did not. According to research published in the Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, this reflects the behavior exhibited in many retail environments.

As they write:

The emotions related to social connections and sociality emerge as significant dimension of the shopping experience and they might influence both the satisfaction of shoppers and their wish to come back to a given store.

(Source)

Social interactions directly impact conversion and retention. Said simply:

Social interactions are crucial to the shopping experience.

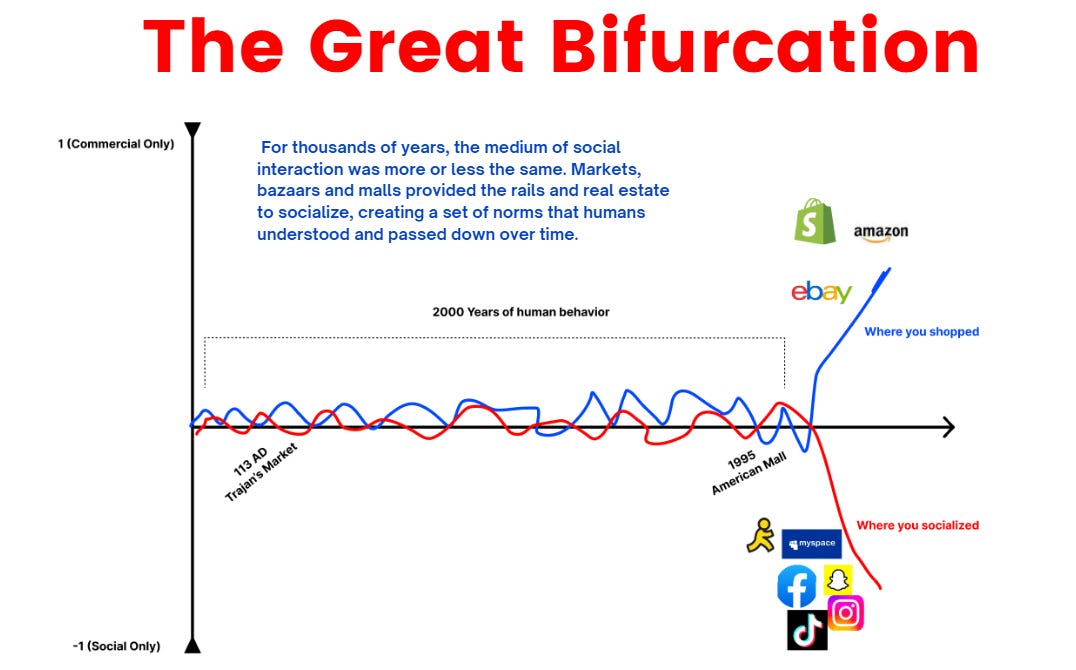

The Great Bifurcation

Branded retail environments exist to facilitate socialization. Indeed, throughout history, commerce enabled social interaction. In Ancient Rome, Trajan’s Market, thought to be one of the world’s oldest shopping malls (113 AD), hosted commerce from across the Empire. This trade enabled trust, this trust facilitated social collision. Trajan’s Market sprouted several Roman taverns and large concert halls as commerce enabled ‘socialization’ to osmose through the public strata.

Indeed, since the dawn of civilization, commerce and social interaction have been intimately intertwined. This holds true up to the contemporary, where modern malls have existed as a center of our economic and social lives.

But with the advent of the Internet, for the first time, the places where we shopped and where we socialized became completely bifurcated.

Consequently, the development of the Internet economies in the West spliced this inherent relationship of commerce and socialization and led eCommerce and social networks to branch into two different verticals.

Once untangled, the online spaces for social interaction and shopping calcified along the poles of utility. Where we shop online only enables shopping. And after a failed swing at commerce, as we explored in Social Media has a Commerce Problem, where we socialize only enables socialization.

Because of this, the success of eCommerce in the west became entirely dependent on social media networks, specifically Facebook and Google, to create a link between where we shop and where we socialized. This link manifested itself as attribution. Demand generation and discovery happened on Instagram, TikTok and Google, conversion happened on Shopify, Woo Commerce, Wordpress and bespoke sites.

But once attribution was impaired and we learned how the sausage was made, the entire house of cards crumbled.

People have blamed the impact of Apple’s ATT changes on social media marketing, specifically Facebook, as the culprit for this disappointment. Yet, I don’t think that’s completely fair; what Apple’s changes did was cut off Facebook’s ability to map a delayed transaction to a previous ad impression. Facebook’s ability to collect certain information about users off platform was impaired, yes, but Facebook also relies on purchasing this information from third party vendors. It also has a treasure trove of historical data on its users, as well how they intrinsically interact with Facebook and Instagram content on an ongoing basis. This progressive interest behavior, paired with the world’s best social graph, trains their models to be pretty good at know who their users are and what ads are most compelling to them.

The truth is much more endemic. The demise of DTC as a business model is not a product of a black swan event of corporate jockeying between Apple and Meta, but the natural consequence of a paradigm that was on life support years before ATT opt ins.

Why is DTC “dead”? We will explore in more detail in a subsequent post.

Love the infographic on the Great Bifurcation. Curious if you think the poles of Social + Commercial start to converge toward each other with the advent of TikTok's shop button, IG Shop, the rise of creator-first commerce like ShopShops or livestreaming on commerce specific apps like Whatnot.