In September, Instagram announced plans to "drastically scale back its shopping features as it shifts the focus of its e-commerce efforts to those that directly drive advertising".

Unfortunately, it seemed like the subsequent commentary oozed more with Meta schadenfreude than with critical investigation.

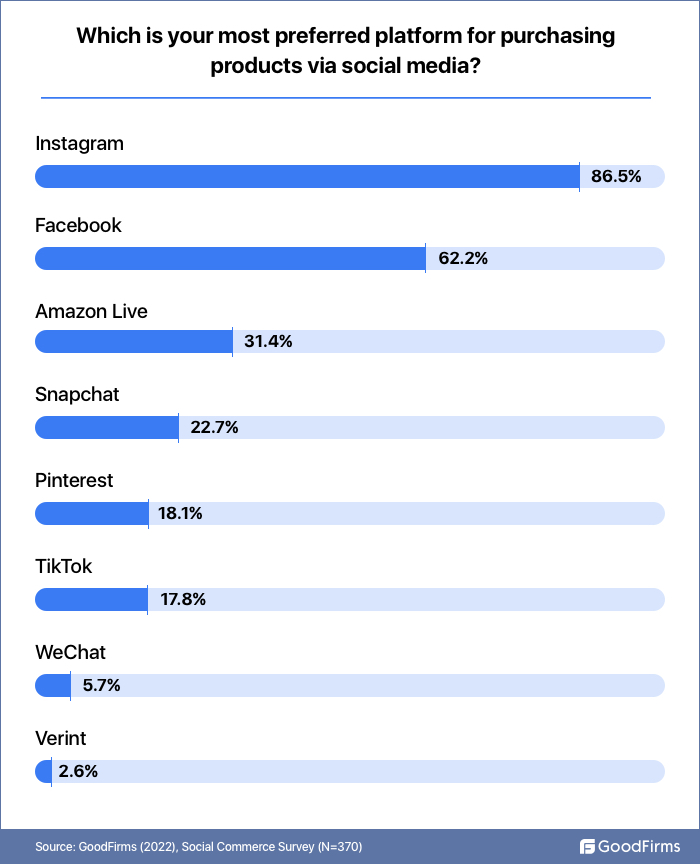

Why was commerce unsuccessful on Instagram, which according to study by GoodFirms, is by far the most preferred social platform for purchasing products?

This essay will seek to answer that by exploring a few topics:

The Logic of the Feed

The Six Content Types on Social Media

A Product analysis of Instagram Shop

A Critique on the Consensus

The Logic of the Feed

To understand the strategic commerce initiatives of Meta and TikTok, one must understand the logic and incentives of their core product: the Feed.

Instagram’s feed is built on two things:

A complex algorithm that shows users a blend of content that they will probably enjoy based on who they follow (social graph) and what they like (interest graph), and;

A modular unit of inventory that is interchangeable between user generated posts and advertisements.

Instagram modularizes its inventory so that the atomic units of the feed flow seamlessly in concert with each other. This reduces the friction for users to engage with the content of the Feed.1

For UGC, this engagement manifests as either a like, comment, click or share. Liking a friend’s post is a lagging indicator of a user receiving value from the platform (a user saw content that they enjoyed), and essentially serves as a micro currency that rewards the post’s creator for their contribution to the platform in the form of social capital and status (measured in likes/follows).

This dynamic creates a flywheel where Instagram gains 100% leverage on user engagement to:

Improve their ability to understand what content and user profiles a specific user likes to engage with (training their recommender algorithm);

Create a social capital system that completely outsources rewarding creators for their output;

Re-engages users with a delightful, rather than invasive, notification that other users have liked a post.

These elements coincide to create increasing returns to scale that solidifies Instagram’s network effects and keeps users retained on the platform.

This helps Instagram acquire new users and lowers churn, which increases net user growth.

As a result, Instagram now has more users (and unique feeds) to distribute ads to. This helps:

Keep ad prices down as it increases supply (helping with advertiser retention)

Increase net revenue as they can sell more total ads

Maintain the optimal UGC-to-ad distribution (preventing churn) as:

New users supply UGC

Existing users have increasing returns with each marginal post as they earn more likes/followers

Thus, at an atomic level, Instagram (and TikTok) earn incredibly micro, but critical, indirect marginal revenue with each UGC engagement as it incrementally improves their retention, which incrementally improves their net user growth, which incrementally improves both their ad supply and pricing power, which incrementally improves their revenue.

Ad engagement works more directly. For engagement-focused ad inventory (which we think of as 'brand marketing'), engaging with an ad allows Instagram to directly monetize that action with advertisers as the conversion location happens directly on the ad in the form of a video view or post engagement.

These ads tend to have a ‘Learn More’ call to action that directs users to an external website via the in app browser. Importantly, however, the conversion event has already occurred (a click) and the subsequent customer actions tends to be purely informational rather than commercial, as the campaign is focused on top-of-funnel awareness and brand equity.

This does two things:

Improve Instagram’s ability to understand what ads a specific user likes to engage with (training their recommender algorithm);

Prove an incremental return on ad spend (ROAS), which allows them to charge more for incremental distribution of ads.

For sales focused 'direct response' ad inventory, the conversion location happens outside the ad inventory (either an external website or app) as the conversion event occurs in the form of a more involved action such as making a purchase.

But as I wrote in How the Sausage Gets Made: Digital Marketing & Attribution, Instagram (and TikTok) can no longer map a delayed transaction to a previous ad impression. Rather, they can only deterministically attribute that conversion event when it happens within the in app browser (which has come under scrutiny) or the in-app checkout immediately after ad impression. But this is not how users tend to shop, as we will explore, and so social media networks must rely on probabilistic modeling to attribute off-platform conversion.

But unlike the advertisement model, the value proposition for social commerce is to seamlessly unite content and commerce, creating a new channel for merchants to drive sales directly within Instagram. However, this promise cannot be encapsulated directly in the Feed (or Stories or Reels) given the modularized form factor of in-Feed inventory.

Let’s explore why.

Square Peg, Round Hole

A full-funnel shopping instance is more robust than an ad or UGC. It requires many steps and engagement types to arrive at a monetizable action (a fee on a transaction).

As Instagram has learned, they cannot change the form factor of the atomic unit of inventory else it disrupts the entire logic of the Feed. As a result, they have to ‘bolt-on’ commerce atop pieces of media, which creates clunky shopping integrations and a disjointed checkout experience that requires as many steps as the existing online journey.

Consequently, commerce must live outside of the Feed, in its own isolated ‘Tab’.

Thus, assuming a constant total amount of time spent on the platform, engaging in commerce on Instagram comes with a direct opportunity cost: leaving the Feed and other social/entertainment focused surface areas like Stories and Reels.

This is orthogonal to Instagram’s and TikTok’s superpowers and value proposition to both users and advertisers— the distribution of social and entertainment UGC via surface areas like the Feed, Stories and Reels. Users simply gain the most utility in these spaces, and by doing so, are willing to bear the cost of advertisements.

Moreover, the ‘Shop Tab’s value proposition has a number of redundancies. Mainly, the Feed, itself, allows users to discover shopping instances through the brand and influencer accounts that they actively follow (or might like), and through the various advertisements shown to them.

This top-of-funnel discovery has both better supply and more supply from which to make distribution decisions from than Instagram Shop. Indeed, nearly every brand and business is a social user on Instagram that has an account that I can follow, a fraction are Instagram Shop users. By following them, I can see organic updates from them in my Feed or on Instagram Stories, which may prompt a shopping instance as a form of organic marketing.

Likewise, there are more and better supply of influencers whom I can actively choose to follow base on my interests and often post UGC and promoted posts that better match my taste and spur shopping instances as well.

By having a larger volume of supply and better and more diverse content types that aren’t purely commercial, the Feed’s recommender algorithm makes better distribution decisions and creates more utility for the user.

The design and logic of a primarily entertainment-focused Feed thus subsidizes this secondary, commerce-focused value proposition by seamlessly interchanging fully-commercial ads and quasi-commercial organic UGC with purely entertaining UGC inventory.

Said another way, it is a tax users must, and are willing to, pay in exchange for the Feed’s ability to delight them by (1) having great content and (2) making great distribution decisions of this content.

Instagram Shop essentially has to compete with the Feed for UGC to bootstrap the supply of its own network. But given the feed’s abilities to subsidize commerce with purely entertainment focused UGC, it has (1) more fragmented supply and (2) more compelling value proposition to users.

Thus, it has more users and more time spent. This offers better monetization for supply, who either seek to monetize their production (the content) via likes and social capital, or via top of funnel customer acquisition because the Feed has better and more efficient distribution.

Content Inventory Spectrum

Let’s explore this thesis more empirically. You can understand the Feed as a medium that distributes a bundle of content types. These content types vary based on their value proposition. On one of end of the spectrum are purely entertainment & social focused UGC. On the other end of the spectrum are purely commercial ad products.

There are two types of organic UGC that create the most utility for users. Type A inventory are post from creators that users follow, or that the Feed recommends, that provide pure entertainment utility. Type B inventory are posts from friends that users follow that primarily provide social utility (with some entertainment) as it allows for a user to stay in touch with people they know.

Additionally, the Feed is composed of a subset of Type A inventory that a user does not follow but is recommended based on their interests and following. These show up in the feed as “Suggested Posts”, a clear response by Instagram to (1) compete with Tik Tok and (2) prioritize creators (and thus entertainment utility) over users (and thus social utility) by leaning more into an interest-graph Feed.

An easy way to delineate the two is by considering the different function that a user’s like serves for the respective posts. For Type A inventory, user likes are commoditized; each like has the same value and the creator seeks to maximize the total number of likes. With Type A inventory, the user and the creator have a unilateral relationship: I follow a creator but the creator neither follows me back nor differentiates any additional value between my like and another user because there is no social context.

For Type B inventory, the follower has a bilateral relationship with the creator. A like is not just a currency but a form of communication between friends. Each like has different value depending on the user, as the creator has a relationship with the majority of the people rewarding their post with likes. A like from a girl that you have a crush on is much more valuable than a like from your grandmother (except if its my Mommom).

Thus, this inventory takes on a new form of utility that I define as social, as it is a form of communication, and a user receives value because they can send a social message (in the form of a like) to someone they care about, rather than simply finding the post entertaining, and they intuitively understand that the individual will both recognize the value of the message and attribute that value to the user.

Moving along the spectrum, we arrive to Type C inventory, which are organic posts from business users. These are pure UGC and do not intrinsically link to an integrated Call to Action that leads to a shopping journey, but they do create brand awareness and seed the hints of commerce.

Towards the center of the spectrum, we arrive to Type D inventory, UGC that is quasi-commercial in nature. These are posts from businesses and creators, sometimes as a co-owned post, who leverage their Instagram distribution to directly promote a brand or product to their audience via the Feed.

While these posts have commercial intent, they do not have an natively integrated Call to Action (besides a reminder) that easily leads a shopping journey. Instead, they have a clunky redirection of pointers and links. The utility a user receives from these posts are mostly commercial (via discovery), but the creator themselves has bootstrapped their audience through their ability to create entertaining posts that users enjoy consuming.

Type E inventory are the most commercial type of organic UGC inventory. These are posts from brands, creators and businesses that are organically distributed in the Feed to their following. These posts have an natively integrated Call to Action (“View Shop”) that then directs a follower to the respective brand’s Instagram Shop page. This feature is only available to brand’s that have Instagram Shop Pages; there is no similarly integrated Call to Action for organic UGC inventory in the Feed to link to an external site.

These posts are the closest that Instagram gets to ‘social commerce’.

Lastly, Type F inventory are ads. Type F inventory are purely commercial in nature and have a natively integrated Call to Action for both top-of-funnel brand awareness (“Learn More”) and lower funnel ‘direct response’ (“Shop Now”). While users receive commercial utility from this type of inventory in terms of seeding demand and discovering potential new shopping instances, it is a net negative source of utility as it comes at an opportunity cost to inventory types A-E. People dislike ads!

Ideally, the utility created by bundling A-E with F provides ample surplus to offset this burden. When consumed in aggregate, the cost is less explicit and flows interchangeably amidst the various types of inventory and value propositions that the Feed distributes. That is the power of the bundle.

Thus, the aggregate utility of the Feed is the integral of the distribution function that determines what inventory type is shown and how frequently.

To test this hypothesis, I went through my Feed and categorized 154 subsequent posts by Inventory Type. I then gave each Inventory Type a coefficient (a score) based on the relative utility of the Inventory Type. To keep it simple, I applied a decay curve to posts C-E.

The post frequency by Inventory Type was as follows.

Type A inventory made up over half of the inventory shown in my Feed. Of these posts, I did not follow 20% of them.

Interestingly, the Feed distributed more ads than Inventory Types B-E combined (147% more to be exact). 82% of my Feed is either Type A (entertainment-only UGC) or Type F (commercial-only ads) inventory.

Clearly, Instagram is focused on supporting their top creators with increased distribution (both organic and recommended) and leaning into interest-based inputs to its distribution algorithms. This comes at the sacrifice of both its users’ social graph (Type B) and small business/creator organic posts (Type C-D). While I imagine Instagram’s algorithm seeks for more than 2% of the Feed to be Type E inventory (the ‘View Shop’), lack of merchants onboarded to Instagram Shop limit its distribution.

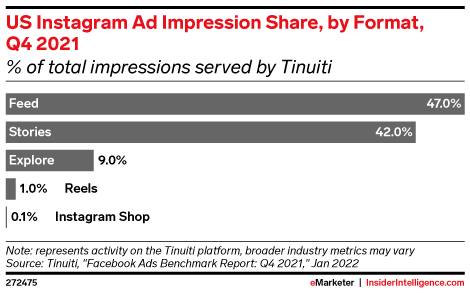

More importantly, as observed, the anchoring value of entertainment-focused Type A post is massive. This is critical to the Feed’s ability to monetize inventory space via ads. If you were to remove Type A inventory from the bundle, which is the premise behind Instagram Shop Tab, the network would experience tremendous churn. This is referred to as marginal churn contribution value. This helps explains why the ad impressions on Instagram Shop are so feeble.

Extrapolating the analysis of my Feed, Instagram currently operates at a 52%:29%:19% distribution ratio of A:F:Everything Else. Consequently, the vast majority of the user experience is dictated by the positive and negative utility users receive from consuming the most frequently distributed (and polarizing) inventories in the bundle: Type A and Type F.

Thus, even if more brands onboard to Instagram Shop, to materially increase Type E “social commerce” inventory in the Feed, Instagram would have to show less Type A inventory or less Type F inventory2. Less Type A inventory create less consumer surplus (worsening the user experience and potentially leading to churn). Less Type F inventory would generate less revenue and weaken Instagram’s value proposition to advertising partners who mainly rely on the platform for customer acquisition & advertising, which is a 5x more important priority to brand executives than viewing Instagram as an additional sales channel.

Consequently, Instagram Shop has struggled to natively leverage the most powerful user behavior (scrolling the Feed), and instead has become its own siloed shopping destination.

Incremental & Underwhelming

The results, thus far, are underwhelming. When I open Instagram, it takes me one click (to the Instagram Shop tab button) to get to the following views. As you can see, Shopping on Instagram is simply a catalog of static images, sorted in no particular order, with no information on price, sizing, reviews, brand name, product details, etc.

Compare this to Amazon. In the same two-step process (visiting Amazon and clicking ‘Shop New Year Sale’ banner), I get to following view.

Amazon’s product is clearly superior from a product design perspective.

It’s consistent design (product image on white background) makes the UI more seamless. It’s persistent filters allow a user to easily adjust and sort the listings by category, price, customer reviews, and more. Importantly, it lists the names of the brand and the product. Moreover, the Discount and Deal badges create urgency and lock-in to the platform. Last by not least, Amazon has far superior supply, which allows them to offer far superior discovery.

As a result, users do not organically visit Instagram Shop to begin their shopping journey, discover a new product or search for something to buy.

Instead, to drive demand to Instagram Shop, Instagram essentially has to advertise Instagram Shop in the Feed. Thus they strip away the top-of-funnel discovery from their seamlessly integrated social commerce promise. Instagram distributes ‘discovery’ as a ‘direct response’ ad in the Feed while the remainder of the funnel lives in Instagram Shop via Brand Pages, Product Details Pages and Instagram Checkout.

These ads often repurpose and promote organic shoppable posts like Type E inventory and boosts them with product tags and ‘View Shop’ Call to Actions. Indeed, merchants have to pay to advertise in the feed to drive traffic, much like they have done previously to drive traffic to their Shopify sites.

Thus, ‘social commerce’ relies on the same Feed, algorithm and distribution decisions as previous direct response ads. The promise, instead, is to lower CAC by improving conversion rates because the conversion location is more convenient to the users within Instagram.

Yet, these storefronts inherently result in users leaving Instagram, the very action they are trying to avoid. Why?

Shopping decisions, especially on Instagram and TikTok Feeds when a user is at the top of the funnel and is either: (1) open to discovery or (2) not thinking about shopping at all, comes with the human tendency to get feedback and recommendations, and see what other likeminded people think. In these instances, the diligence process is important.

Instagram storefronts lacks critical elements that users depend on for the diligence process, such as product reviews, FAQs, size & fit guides, product details, and other conversion optimization tools. As you can see in the below view, Parade only has one product review on it’s Instagram Shop Product Details Page, two pictures per product, limited information and zero FAQs.

This is a materially worse diligence and checkout experience than what is found on Parade’s DTC site.

Thus, this leads users to leave the platform to traverse the Internet, and perhaps most likely, to convert at a later date via a Shopify site. This user action is not monetized by Instagram as the conversion location for such an ad is within Instagram Shop, not an external site.

Moreover, a user sent to a website rather than Instagram Shop Product Details Page has a higher likelihood of converting, which creates better ROAS, which creates more demand, which increases ad prices, which increases revenue.

As a result, Instagram Shop ads earn less ROAS than traditional direct response ads. This lowers the price that Instagram can charge for these ad. If the combined price of the Shop ad plus the 5% take rate is less than the price of a traditional direct response ad, it becomes a suboptimal distribution decision for Instagram.

Indeed, each distribution of a Shop ad (and social commerce instance) in the Feed comes at the cost of a direct response ad. While Instagram earns 5% take rate on GMV via Instagram Checkout, if they are creating suboptimal ROAS, specifically compared to another one of their products, they are essentially borrowing value creation from their customers to serve their own interests.

Moreover, if a user is spending the same amount of time in the app, but more relative time in Instagram Shop and away from the Feed or Stories or Reels, that engagement is coming at an opportunity cost of entertainment/social-focused UGC, which is critical to the health of their ecosystem as it is the flywheel that incentivizes and rewards the supply of content.

Thus, by wading deeper into commerce, Instagram realized that they disrupted the logic of the Feed that created increasing returns of scale to improve their ad distribution decisions over time. More, it is replacing direct response ad inventory of with lesser performing social commerce ads.

Given all of this, is important to reflect on why Instagram became the most preferred social shopping platform in the first place.

The answer, I believe, is quite simple.

Lose the Battle, Win the War

All social media networks’ commerce value proposition remain the same as that of their advertising business — superior distribution leads to superior discovery, which leads to superior demand generation.

Users discover products via Instagram’s distribution decisions of UGC in their Feed, Stories or Reels, as well as via Instagram’s distribution decisions of relevant ads. Instagram offers the best discovery, as evident by the below survey, which is because it has the best supply of UGC and the best advertising infrastructure.

Yet, discovery and conversion are not seamlessly integrated in a single surface area. Rather the two siloed spaces (the Feed and Instagram Shop) are clunkily duct-taped together in a manner than weakened Instagram’s superpower of discovery at the behest of a value proposition that is less exciting to users and merchants alike: driving direct sales. Ads distributed in the Feed remain the primary driver of social commerce sales on the platform.

Indeed, regardless of the underlying platform, even after clicking through ads, consumers aren’t keen to adopt social media platforms’ proprietary tools like Instagram Checkout or buying directly from livestreams on Facebook.

As such, Instagram has shifted “the focus of its e-commerce efforts to those that directly drive advertising".

The semantics of this announcement are important. Instagram, I believe, identified this local maxima and understood that their efforts to own conversion with commerce came at a cost of their ability to offer superior discovery through the Feed — and with it monetizing said discovery via ads.

While the prevailing consensus views Instagram’s scaling back of shopping features as an admission of defeat, I believe it is the opposite. This redirection is not a failure, but a triumph of focus that diverges from their main competitor (TikTok) and doubles down on their ultimate competitive advantage: creating demand via highly efficient and programmatic distribution of UGC and ads.

In short, social media marketing is still effective at generating demand, what they can't do is drive conversion, as Instagram has wisely learned.

Nor do I believe, will they ever.

Closing Thoughts

As we find ourselves on the precipitous of a category defining before-and-after in commerce, the future, as always, is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed yet. Locating that future requires pattern-matching and curiosity, but most of all, it requires work.

This is the first in a series of posts that seek to build up to what I believe the future of commerce will look like. Part of this process involves putting in the work to eliminate potential future states with high degree of conviction. I believe a great insight is one that contradicts the consensus by interrogating the accepted probability weighting of potential future states. Often arbitrage emerges.

People tend to allocate such weighting based on two things:

the wisdom of the herd (confirmation drift)

What’s easy (Occam’s Razor)

Yet, Occam’s Razor suffers from outcome bias. It is a principle entirely dependent on perspective: it seeks to forecast the future using the information and models that explain the past.

Indeed, things seem glaringly obvious in hindsight after we have adjusted our mental models to reflect the actual distribution how things unfolded, but at the point of forecast the explanation turns out to be extremely messy.

Today, a doctor would easily diagnose a patient with a cold and fever with COVID. But in February 2021, the same symptoms — indeed the same inputs — would most likely lead to a completely different diagnosis. While today we could easily look back and diagnose such cases as COVID, in the moment there simply was no widely accepted model that led to such a discrete output.

That is not to say that such thinking does not serve a critical purpose. It’s an easily memetic model to process information and make a forecast, prediction or diagnosis. This allows for speed and consumes less time, energy and resources.

But this is only true when the discipline is relatively stable and time is not an exogenous factor (also known as unknown unknowns). Meaning, regardless of whether the moment was today, a million years ago or a million years hence, the rules of physics allow me to precisely forecast the density of an object by dividing it’s mass by it’s volume. For doctors, this is less true although diagnoses models tend to hold up for decades on end — how we diagnose cancer has remained more or less the same for well over half a century.

But in the world of venture capital and technology, the fundamental premise that propels the industry is that future will be different than it is today. Technology is a force that destroys paradigms and the models that explain them. As a result, forecasting the future is an incredibly discrete process, relying on the wisdom of the herd and what’s easy often has limited fidelity.

Yet, we are human. Humans seek the path of least resistance. In this discrete scenario of determining the proper distribution of how the future of commerce will unfold, I believe the consensus severely overweighs the probability that TikTok or Instagram will dominate social commerce because (1) there is minimal social cost to confirming the consensus and (2) it is the easiest conclusion given the inputs (they are both attempting it) and the existing model that rationalized their success in social media.

Hopefully, this essay helped explain why I believe this is wrong.

TikTok, to its part, takes it one step further. The genius of their feed is not a materially better recommender algorithm (in fact it is interchangeable to Instagram’s) but a feed composed of video inventory that takes over the entire screen, which removes the action (and friction ) of scrolling.

This is because Instagram usage is relatively flat, meaning Instagram can only show a finite number of inventory.