Bernard: Ivan is fine but he's not a serious guy, he's a philistine.

Frank: What's a philistine?

Bernard: It's a guy who doesn't care about books and interesting films and things. Your mother's brother Ned is also a philistine.

Frank: Then I'm a philistine.

Bernard: No, you're interested in books and things.

Frank: [pause] No, I'm a philistine.1

In 2005, Noah Baumbach debuted his semi-autobiographical film, The Squid and the Whale, which quickly became the talk of Park City during that year's Sundance Film Festival. The film is a wry portrait of emotional distancing, family fracture and the vulgar underbellies of the intellectual class in 1980s New York City. But, arthouseness aside, the story is quite formulated: it follows two sons as they deal with their parents' impending divorce, the gravity of which swallows each into competing parental allegiances that are fraught with emotional manipulation, self-sabotage and disillusion of equal magnitude.

The Squid and The Whale, quite literally, is a manifestation of a classic narrative motif dating back to the Greek mythos of of the Teumessian fox, which can never be caught, and the hound Laelaps, which never misses what it hunts (or to its eastern counterpart of Han Feizi's Shield and Spear). Today, the 'Irresistible force paradox' is more commonly formulated as "What happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object?".

And while not perfect, nor as comedic, such a paradox has slowly been playing out elsewhere. Specifically, The Squid and the Whale could be another name for Amazon and Shopify, two inherently different beasts of symmetrical influence and magnitude in the unfolding narrative of eCommerce, that have found themselves in a parlay as they approach this ever changing world of online shopping from two competing perches with fundamentally different models and tactics.

The Whale

Dating back to its days as an online bookstore, Amazon has always seemed to be one step ahead: investing in integrating non-obvious verticals long before Warby Parker’s Neil Blumenthal (no relation, but maybe?) thought to sell glasses over the internet or Forbes published the acronym 'D2C'.

Take, for example, fulfillment. In 1999, Amazon had seven fulfillment centers in the US and 3 more in Europe. It then formally announced Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) in 2006, wherein they began offering Fulfillment-as-a-Service (FaaS) and integrating this as core to its value proposition for users for both first and third party merchants alike. Again, before the first DTC 1.0 startup had a landing page, Amazon was already foreseeing that the internet will enable a new era of retail, and their ability to internalize potential network effects would i) accelerate escape velocities and render competitors obsolete and ii) create a demand for new services that will open up adjacent revenue streams.

Today, Amazon has entered the market as the top third-party logistics carrier globally. They now employ more workers (648,000) than either FedEx (450,000), UPS (481,000), or USPS (497,000) — up from just 117,000 in 2013. And they’ve built the infrastructure capabilities that could support a small army: 390 warehouses, 50 planes, 300 truck power units, and 20,000 delivery vans.

Indeed, perhaps Jeff Bezos’ greatest skill is his ability to conceptualize exponential growth and make long term investments toward a future state that 99% of people cannot envision. In order to continue to attract more customers, Amazon needed to offer the lowest prices and the most extensive assortment of products. One way to do that was the traditional wholesale model — purchasing products from manufacturers and then selling them to customers. However, this model simply replicates the offline store, is incredibly capital intensive and locks free cash flow in inventory.

In his book The Super Store, Ben Stone succinctly outlines the mechanics of this loop.

Lower prices led to more customer visits. More customers increased the volume of sales and attracted more commission-paying third-party sellers to the site. That allowed Amazon to get more out of fixed costs like fulfillment centers and the servers needed to run the website. This greater efficiency then enabled it to lower prices further. Feed any piece of this flywheel, they reasoned, and it should accelerate the loop.

Feeding any piece of this flywheel is exactly what Amazon has done. Amazon has fed its customers (and itself) by doubling down into what it does best, effectively taking food from its third party merchants in order to ensure its users have a steak dinner.

Specifically, Amazon leverages the intense competition amongst their merchants to force them to lower prices, modularize to their selling ecosystem, and 'pay' for differentiation (more on this below). As a result, they pass value and margin to the consumer (lower prices and more buying options) and along the way charge a take rate for using their integrated solutions. While some of these fees, such as Amazon Prime memberships, are paid by customers, the majority are paid by merchants as a necessity to survive. Amazon has smartly surmised that feeding the third party seller services is a better source of calories as they earn greater margin compared to their traditional retail business and can reinvest the free cash flow back into loop, furthering defensibility, enhancing the customer experience and strengthening their control over the ecosystem.

As such, Amazon's Third Party Seller Services revenue was $25.09 billion in Q2 2021, up by 38% year-over-year from $18.20 billion. From $53.76 billion in 2019 it increased by 50% to $80.44 billion in 2020.

At the same time, GMV growth is being driven by the marketplace as third-party merchants are outselling Amazon's retail business.

For Amazon's network of merchants, the challenge then becomes: how do you stand out? The problem for them is that, on Amazon, brand matters very little. In fact, 78% of product searches on Amazon are unbranded as consumers shop on Amazon for low prices, marketplace trust, easy product comparisons, reviews, seamless payment, fast delivery, etc. — essentially everything but the merchant which sells them the product.

Instead, merchants need to pay for differentiation. Differentiation on Amazon is simple: it is measured in star rating, search rank and the ability to display the Prime Delivery logo. In order to stand out on search results, merchants need to offer the lowest price (paying the customer), and/or advertise (paying Amazon) via sponsored product or brand display ads.

Furthermore, merchants can attract customers by offering Prime Delivery (paying Amazon for their FBA). Marketplace Pulse estimates that 85.5% of Amazon’s top sellers use the platform’s fulfillment network. Overall, this is part of a general shift away from Amazon's retail business, which is susceptible to supply chain issues, inventory risk and low margins.

To summarize, Amazon's magic derives from its ability to commoditize merchants and create a modularized supply, then integrating this network with fulfillment (FBA & Prime Delivery), payment services (One click check out) and customer experience (namely quantify brand via reviews and ratings and an almighty algorithm).

As a result, Amazon owns the entire experience from an end-user perspective. Amazon customers still use the same search engine, filter based on the same attributes (ratings, Prime Delivery, etc.) and get the same Amazon branded package when they place an order, regardless of it being supplied by a first party or third party supplier. Consequently, Amazon has rewritten its own definition of 'differentiation' which they utilize to extract value from their merchants.

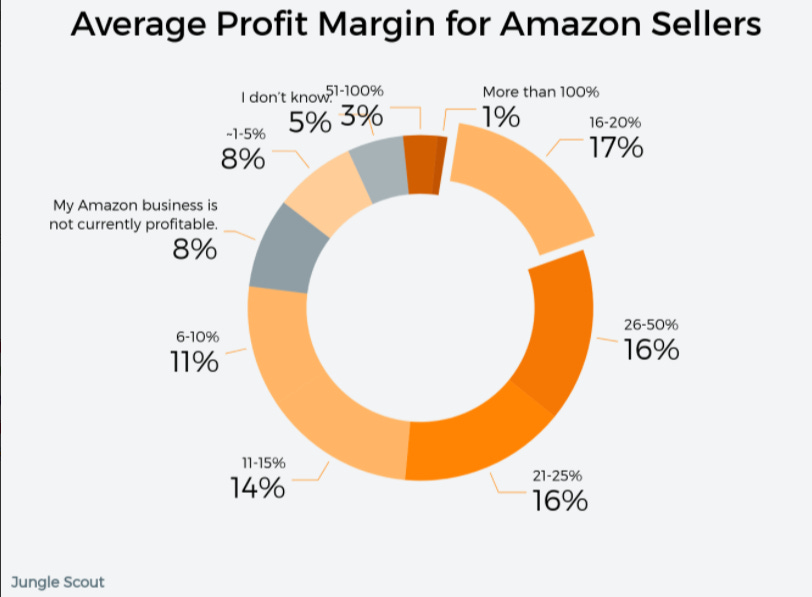

On the other end of the trade, merchants sacrifice margin for access to demand. 74% of third party merchants on Amazon report having less than 25% profit margin.

Amazon continues to put distance between them and all of their direct competition. But, there is another species maneuvering below the tide of equal might, yet different biology. A company that succeeds by enabling its merchants to differentiate and externalizing network effects to create a mutually beneficial ecosystem.

The Squid

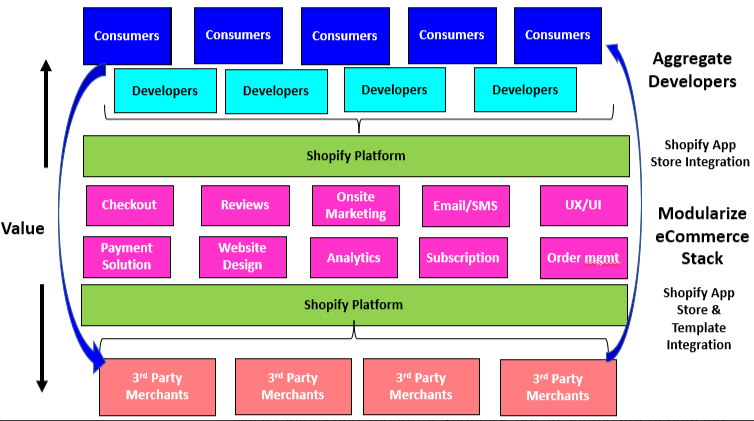

In many ways, Shopify is the antithesis of Amazon. Amazon has built a monopoly by aggregating demand and bludgering merchants into perfectly commoditized squares that they can plug into their seller ecosystem. Shopify aggregates developers to build modularized tools that merchants can use to adjust their geometry to best serve their consumers and differentiate themselves, while allowing the developers that build these tools access to the 1.8 million merchants on the platform.

Instead of integrating their ecommerce and selling solutions, Shopify has made theirs completely composable. Whereas Amazon has aligned itself with its customers and seeks to own their entire customer experience from search to unboxing, Shopify has aligned itself with merchants and seeks to be invisible.

As such, Shopify's anatomy looks fundamentally different to Amazon's.

What's interesting, though, is Shopify is not an aggregator of demand. Rather it is a platform that provides their users (merchants) with tools and access to a plug-and-play marketplace to improve their eCommerce experience. Shopify, to that end, does not compete with Amazon head on yet can offer an equally compelling value proposition to merchants.

Let's use another analogy.

Amazon gives their merchants access to the best fishing pond, but with the caveat that they purchase their reel, line and bait from Amazon. Shopify gives their merchants the access to the best reel, line and bait on the market, but sets them on their way to fish in various ponds of the merchants choosing.

Said another way, Shopify's differentiator is its ability to facilitate differentiation. They do so via their developer network, and in similar maneuvering to past Amazon strategies, have smartly doubled down on feeding the most nutrient dense part of their flywheel.

In August, Shopify made a significant change to its terms for app developers. The e-commerce platform previously took a 20% cut on revenue generated annually by apps. However, starting in August, it will allow developers to pocket 100% of the first $1 million they make on its platform, a benchmark that resets every year. For apps that exceed that threshold, Shopify reduced its take to 15% of “marginal” revenue.

The impact of this revenue-share change was immediate as Shopify paired a healthier developer ecosystem with COVID-induced ecommerce tailwinds to record setting levels of merchants joining the platform.

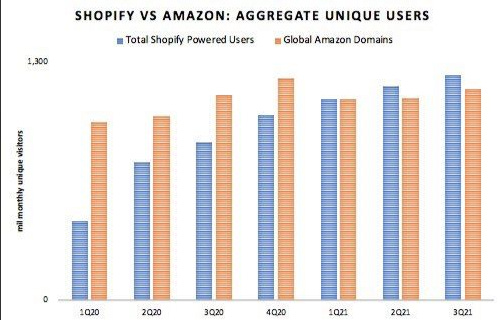

In the process, they overtook Amazon in terms of unique visitors.

Consequently, GMV has exploded.

Last year, 2,300 new apps launched on the platform, ranging from group shopping tools, to cohort analytics to one click checkout. This number equaled the amount of new apps launched over the preceding three years combined. This year, however, Shopify’s app store has added just 600 apps, bringing its total to roughly 6,600 apps built by roughly 5,700 developers, according to third-party database The Shopify App Store Index (via Modern Retail).

Shopify's changes to its revenue-sharing model is a clear example of how differently they feed their flywheel compared to Amazon. To continue app development, which is critical to merchants joining, scaling, and succeeding, Shopify sacrifices their own economics for the growth of an increasingly distributed ecosystem. This is also fits nicely within the tactical strategies outlined by Chris Dixon to support complementary network effects, specifically: "signal long-term commitment to platform success and competitive pricing."

Interestingly, Shopify is taking a similar strategic approach to a very Amazon business category: Fulfillment. From the company's 2019 announcing Shopify Fulfillment Network blog:

Customers want their online purchases fast, with free shipping. It’s now expected, thanks to the recent standard set by the largest companies in the world. Working with third-party logistics companies can be tedious. And finding a partner that won’t obscure your customer data or hide your brand with packaging is a challenge.

This is why we’re building Shopify Fulfillment Network—a geographically dispersed network of fulfillment centers with smart inventory-allocation technology. We use machine learning to predict the best places to store and ship your products, so they can get to your customers as fast as possible [...].

With creators, too, they are looking to do the same by creating an interface between influencers and commerce. Shopify recently hired Jon Wexler who oversaw Adidas' Yeezy Business to run this initiative, doubling down on influencers ability to aggregate demand.

This anti-Amazon strategy has caught the attention of, you guessed it, Amazon. From Dana Mattioli of The Wall Street Journal.

“This year, Amazon has zeroed in on Shopify Inc., a fast-growing Canadian company that helps small merchants create online shops. Amazon has established a secret team, “Project Santos,” to replicate parts of Shopify’s business model, said people familiar with the project.

However, Amazon is not building a Shopify competitor. As Joe Kaziukenas of Marketplace Pulse notes, "Amazon is in the business of getting more people to shop on Amazon. Building tools for brands to host independent stores could drive some revenue and maybe even provide benefits to Prime members, but it would not fuel the Amazon flywheel."

Yet, the Amazon Flywheel is no longer the only virtuous loop on the playground. Clearly, the “Anti-Amazon Strategy” has worked for Shopify. A few weeks ago, Shopify president Harley Finkelstein proudly proclaimed that his company could be considered “the second largest online retailers,” adding the important caveat “if you were to think of us as a retailer.”

Yet that caveat is crucial. Amazon and Shopify are not direct competitors as Shopify is not a retailer. There is nothing to buy on Shopify.com. Compared to Amazon, Shopify extracts very little economics from it's GMV and instead externalizes the network effects of its platform back to its stakeholders.

Closing Thoughts

Amazon has chosen to dominate by being an cold-blooded philistine: aggregating demand, creating a hyper efficient shopping journey free of composable creativity, investing in convenience and speed, commoditizing brand, and winning on price. Shopify, to that regard, is its romanticized counterpart, enabling merchants to differentiate themselves and giving them the creative tools to prosper (or fail) in the process.

Amazon continues to signal its commitment to its marketplace business and has even reduced transaction fees from 15% to 5% for converted traffic originating off platform. This, in many ways, is a direct shot at Shopify and has a single purpose: incentivizing brands to drive traffic to Amazon instead of their own DTC sites and thereby taking GMV from Shopify. Inversely, Shopify has signaled a commitment to their developer ecosystem and shuns suggestion of developing a marketplace to compete with Amazon. Shopify is doubling down on doing eCommerce differently, focusing on the strategy that has helped them grow GMV to 40% of the size of Amazon Marketplace. When compared to the fact that it was just 25% in 2018, that’s pretty good take.

In the final scene of The Squid and The Whale, Walt Berkman (Jesse Eisenberg) returns to the Museum of Natural History and again confronts the Squid and The Whale diorama, with the film ending on a rear view shot of him as he ponders the significance of these two behemoths colliding. As I talk to many CPG entrepreneurs, I can’t help but draw parallels to this scene. More and more, the overlap of merchants selling on both Amazon and Shopify is growing. For these entrepreneurs, Amazon and Shopify are becoming entangled components of their eCommerce business. As such, understanding the difference between them, as well as their complements, will help founders optimize their channel strategy and how they should strategically growing their eCommerce business going forward.

From The Squid and the Whale