Stories as Currency

Revisiting the importance of Stories, and the Magic of Collision

In Youthphoria: A Database of Culture, I wrote about the importance of stories, specifically as it relates to their function as storage systems that record a group or individual’s values, which ultimately aggregate to form a repository of culture.

I love this topic and find that it’s often underexplored, specifically how social media and new formats of storytelling have greatly reduced the storage capacity of each individual story.

As I wrote:

In many ways, user generated content has commoditized stories and their impact on culture. Instead of being composed of a few monolithic narratives that store, record and influence a large amount of an individual’s or community’s values and essence, a collective culture is composed of many weaker commodity-like stories with very short half-lives.

My hypothesis is that this dynamic is one of the primary forces leading to the rise of individuality and the decline of a trusted monoculture that binds together, and enables exchange between, a diverse group of individuals.

This is not to pass a moral judgement on social media networks and technology. I tend to believe they are amoral, neither fundamentally good nor fundamentally bad, they just are. However, should I say they are… incredibly complex systems. So, mapping their impact tends to look like San Francisco’s Lombard Street, a winding and sometimes treacherous journey, yet an important journey nonetheless.

Millennials and Gen Zers are digital natives, and have grown up in an age where the values and identity are constructed via online communication and social media networks. This creates a cultural tapestry composed of relatively weak stories that have little nuance, and so who an individual is is defined of many smaller stores of information rather than a few richer ones. Meaning, people’s essence is composed of many things that lend little interpretation rather than fewer things that lend substantial interpretation.

The latter results in a surface area that leads to implicit trust. Having a smaller supply of stories equalizes culture and creates a bridge between different communities and individuals to share something in common. More, since these stories lend themselves to greater interpretation, it allows for more mutual reciprocity: the feeling of both fitting in, and standing out.

Furthermore, distributing stories via traditional linear rails meant that geography was the main predicator as to which stories an individual would interact with. Grandparents and teenagers alike were shown the same movies at the theater, the same news in the paper, the same books in the library, and the same shows on cable television. This caused natural collision between individuals (and generations) with varying interests and social circles, and in the process led to the serendipity of unlike-minded individuals finding common ground.

In this sense, specific stories take on new use cases beyond just entertainment. They serve as a form of currency that enable exchange between different individuals.

This currency, let’s call it Story Currency, was fungible and accepted across subcultures, communities and individuals. The Story Currency was backed by the stories that the Federal Story Reserve, our collective monoculture, recognized as meaningful stores of value.

These stories were meaningful stores of value because a large population recognized their value as storage systems that effectively captured and influenced a person’s essence and values. This was because (1) they were widely consumed and (2) were nuanced enough that people didn’t have to have the same interpretation of a story’s meaning to find them valuable, allowing for mutual reciprocity across a diverse consensus, thus standardizing the comparison of almost all of the stories we produce and consume.

Thus, the Story Currency (a divisible unit of the stories that underpin much of our monoculture) represented a standard unit of account that enabled the exchange of ideas and values between groups that may not otherwise trust each other, as these groups trusted the currency as an instrument to measure and compare different peoples’ essence, values and qualities as it related to their own.

Indeed, defining your values based on the stories of Christianity or America or even Star Wars opens the door for more mutual reciprocity than does defining yourself based on the values of the aggregate stories you consume on social media.

You might not have the same favorite movie or same interpretation of Christianity, but you trust that the value of the information captured by someone’s favorite movie or interpretation Christianity is equal to the value of the information captured by your own.

Meaning, even if you don’t agree, you know how to measure these stories. It is a standard unit of cultural account.

This implicit trust enables exchange of values and ideas between different individuals and generations. You could exchange with anyone who recognizes the storage of value (and information) captured by the currency, which was pretty much everyone.

But in the world of algorithmic distribution, the stories you now consume are preordained. You are recommended stories based on what people just like you have watched, or see content that your friends and favorite creators have published. This creates an echo chamber where likeminded people see the same weak stories, which heightens the divide between different social and cultural groups and prevents any form of serendipitous collision, while also stymying cross-generational and cross-ideological interaction.

(This, I believe, is what leads to such pervasive trolling and shit-posting online. Within these bubbles of sameness, the evolutionary rules of natural selection takes over and individuals thrash to find any nuanced expression to standout, even if that means succumbing to more base and crude behavior.)

In this new world, there no longer exists a standard unit of cultural account. The stores of information, the stories that define us, are no longer fungible — a movie no longer holds the same relative value as it once did, as the mediums that distribute younger generations’ stories (Tik Tok, YouTube, Roblox) are foreign to older generations.

Thus, the stories that once underpinned our monoculture store less value today that it did previously. This inflation has destabilized the prevailing ‘Story Currency’ that once enabled a standardized form of exchange.

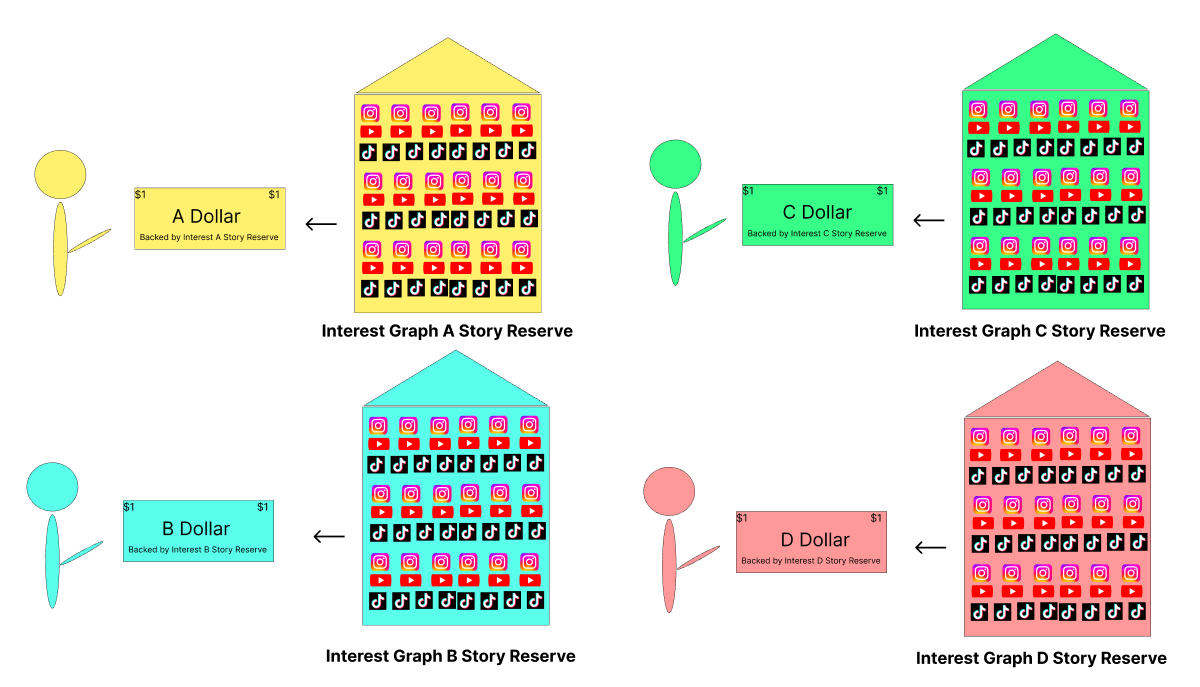

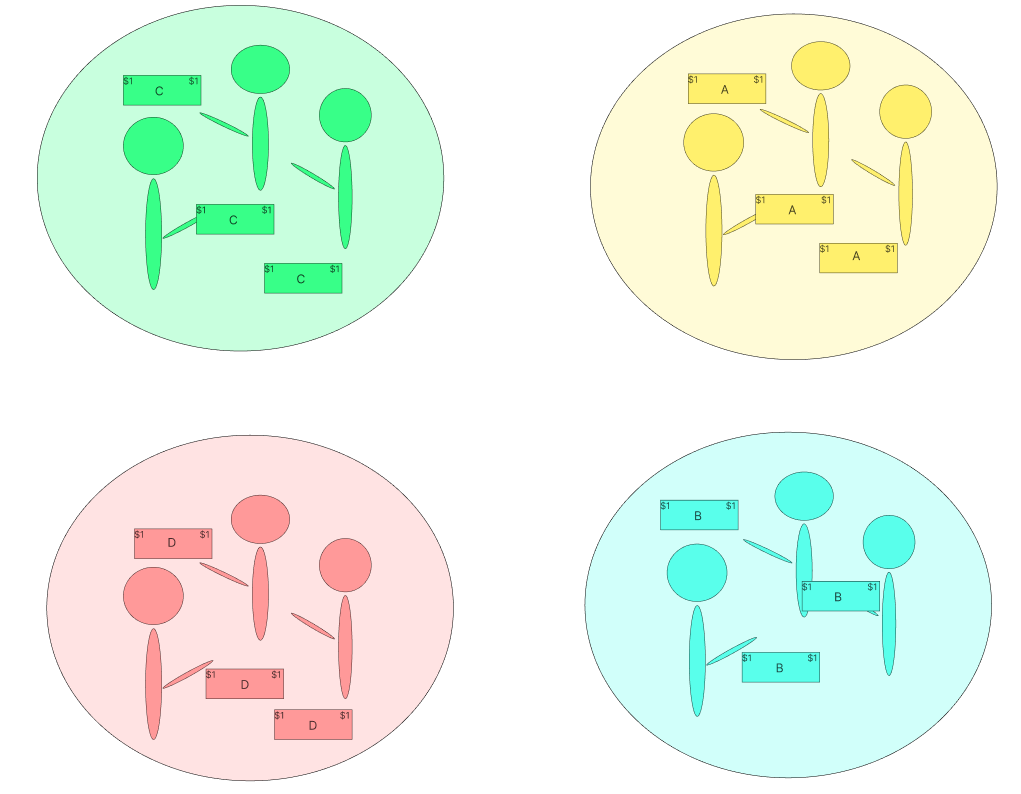

Instead, there now exists a proliferation of microcurrencies backed by smaller, ‘Interest-Graph’ Reserves. These reserve fill their treasuries with the stories that have less distribution and structurally store less information. As a result, there is less opportunity for mutual reciprocity, and so only people with very similar values and interests consume these stories and recognize their worth as stores of value.

Thus, it’s expensive to transact with individuals and ideas and that recognize a different currency (and have different values) as there is no trusted reserve to facilitate an exchange rate of sorts, and so exchange between different subcultures and groups is limited.

Consequently, there exists a fundamental breakdown in intergenerational communication. Asking a 20 year-old her favorite movie might not store as much information as asking a 20 year-old the same question two decades prior would have. The better question today may be who is your favorite Youtuber or Instagram account — and perhaps this stores a relatively sound amount of information, but it becomes less fungible across generations. It’s really difficult for a 40 year-old to evaluate an individual based on that information.

This causes friction between generations and ideological groups and makes it difficult to communicate, pass down and exchange cultural values. We end up retreating into the isolated bubbles of our specific feed-created subculture.

Closing Thoughts

Stories create a codify way for people to more intuitively understand complicated and abstract ideas. The right stories can form a currency that creates trust and enables the exchange of ideas and values between diverse groups of individuals and concepts.

Stories act as the electromagnetic force that puts these collisions in motion. It convinces ideas of different charges to collide instead of repel. It coaxes the stern, unforgiving laws of physics with a sprinkle of alchemy that turns energy into serendipity, fission into magic.

One of my core beliefs in life is the power of collision. Whether that be the collision of ideas, people, contexts or an amalgamation of them all, history is littered with examples of the magnificent breakthroughs and insights produced from the interdisciplinary collision of information.

Newton discovered gravity when he witnessed an apple fall from a tree, not within a lab. Einstein's Annus Mirabilis occurred while working at a patent office, not at Princeton. Roger Bannister broke the impossible feat of the 4-minute mile because of his knowledge of physiology stemming from his pre-med curriculum, a rarity at the time among runners. The Beatles wrote most of the songs of The White Album and Abbey Road while studying meditation and experimenting with psychedelics in India with the philosopher Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Similarly, Steve Jobs cofounded Apple after traveling through India seeking enlightenment and studying Zen Buddhism. Indeed, Jobs likened The Beatles’ creative process to Apple’s own. While listening to a bootleg CD from one of the band’s recording sessions, Jobs remarked, “They did a bundle of work between each of these recordings. They kept sending it back to make it closer to perfect … The way we build stuff at Apple is often this way.”

What should we learn from this?

After you read this, go read something that may not directly be aligned with your interests. Go watch your Dad’s favorite movie for Father’s day. Go read Moby Dick or listen to Bob Dylan underneath an apple tree.

Try to understand as many stories as you can. Become an exchange that can interchange and measure the value of different story ‘currencies’.

By doing so, you can accelerate the collision of different people, of different ideas, of different contexts.

You can make it so that magic does not have to be solely confined to the worlds of our stories.