Youthphoria: A Database of Culture

The Importance of Stories, Euphoria, Self-Expression, Sexuality & Generational Tension

Databases of Culture

There’s a great scene in Hulu’s Pam & Tommy miniseries that subtly underscores the asymmetrical power that narratives have as stores of information. In it, Pam & Tommy are on a plane ride back from Mexico after a debaucherous weekend that ended with their marriage a mere 96 hours into their relationship.

The two strangers-come-partners await takeoff in a stretched out moment of silence. Sensing this, Tommy breaks the ice with some small talk and asks Pam what her favorite movie is, to which she responds Pretty Woman — she loves romantic movies. Pam flips the question back on Tommy, who for his part rattles off a number of horror movies like Child’s Play and Nightmare on Elm Street.

It’s in the awkward moment following this exchange that the too-good-to-be true love affair briefly crashes to earth and the audience awakes from its delirium to be reminded how this story ends: these two are not right for each other.

Indeed, the showrunner deliberately chooses this question to reveal the incompatibility of the two. It’s fascinating how so much can be conveyed with so little.

To me, this scene reveals the power of that specific question: “what is your favorite movie?”, which can be reframed as “what is your favorite story?”.

The question itself is casual and disarming, yet so effective at understanding who a person is. It’s a codified way of understanding a person’s values and stores remarkably rich and nuanced information about them.

While on the surface it may seem trivial — it’s often a question we ask on first dates or during awkward lulls — it’s actually quite Darwinian. We inherently know that it’s fundamentally human to enjoy stories and so we reflexively ask it to strangers as a means to disarm them and ease a relatively awkward situation. Everyone has an answer, so it works. If someone doesn’t have an answer, it’s alarming and a signal in its own right. More importantly, we subconsciously know that we can learn a lot of information about a person and their essence from the question, so we ask it when we are trying to effectively and quickly evaluate a person.

Many of you may not know this, but I am a bit of a cinephile. I’ve written a bunch of screenplays and directed some short films. There are two things that drives my interest in cinema. The first is the flow I get from writing. The second is the profound abstract ability of stories to reflect what’s going on inside a person, a community, or a culture.

Stories are, in many ways, the greatest achievement of humanity — on a first principles basis everything boils down to our ability to share and engage in social constructs like government, religion, etc. that have no physical presence in nature, but rather exist as stories we collectively agree to.

When certain stories take on memetic form, meaning they become widely shared and consumed, it becomes a rich social signal. That's because stories, as storage of information, are not deterministic but probabilistic in nature. Meaning, a story means something different to me as it does to you. We are presented the same information but create different conclusions. Or said another way, the same inputs lead to different outputs depending on the receiver.

A ‘story’ is system of communication where the output information is greater than the input information. The best stories inspire, challenge and cause wonder, and often produce outputs that are many orders of magnitude greater than the original inputs. The most effective stories, as storage systems, structure finite information in a way that leads to various interpretations. An individual’s interpretation tells you a lot about them, and threading all of the various interpretations creates a story’s culture, which contributes to a meta-culture.

As I wrote about in Arriving at The Metaverse, social media has disintermediated Hollywood’s perch as the steward of storytelling and distributed culture creation to the masses. As a result, culture now moves at the speed of social media, and has increasingly been amateurized through user generated content.

But as a result, these cultural objects have become weaker: the inputs create relatively fewer and more homogenous outputs. There’s not much nuance to a Tik Tok video, or an Instagram Post, or Youtube Vlog, nor can they store as much information as traditional storytelling formats (movies and books). That’s part of the reason why memes have emerged as such compelling cultural containers in today’s age. Since the container is so limited in storing nuanced information — it’s simply a picture overlayed with text — it necessitates remixing and repurposing, and memes are built exactly for that.

In many ways, user generated content has commoditized stories and their impact on culture. Instead of being composed of a few monolithic narratives that store and influence a large amount of an individual’s or community’s values and essence, a collective culture is composed of many weaker commodity-like stories with very short half-lives.

Paul Graham wrote in 2016 about what something as simple as there only being three TV stations did to equalize culture:

It’s difficult to imagine now, but every night tens of millions of families would sit down together in front of their TV set watching the same show, at the same time, as their next door neighbors. What happens now with the Super Bowl used to happen every night. We were literally in sync.

So the supply of good stories that contain valuable information has decreased. But it still exists. That means they become even more important signals. And I think examining these stories is a really undervalued mechanism for accumulating data on the behavior of populations. The story does the hard part — collecting, processing and distributing the information — and from there you can start thinking in second order effects.

Euphoria: Sex, Drugs & Face Tattoos

Euphoria, the hit HBO drama series that follows a group of high school students as they navigate love and friendships in a world of drugs, sex, trauma and social media, has been a massive hit for the network.

Per HBO, last Sunday’s episode of Euphoria was the No. 1 most social and No. 1 most talked about broadcast when excluding the Super Bowl. Episode 1 is now tracking at 16.7 million viewers across platforms, just over 2.5x the average audience of Season 1 (6.6 million viewers per episode).

Euphoria’s popularity is partly because of it’s entertainment value — it’s masterfully shot and acted, and has a rather engrossing conflict. But I believe, even more so, it’s popularity is a function of it’s embodiment of the generation it portrays, as the show stores a tremendous amount of cultural information that resonates with the current audience.

So let’s think in second order.

First order: why is Euphoria popular?

Second Order: What does Euphoria’s popularity tell us about it’s subject matter (i.e. information) and audience?

Self-Expression

At it’s core, Euphoria is a show about identity and its protagonists’ various internal conflicts as they try to figure out who they are. For younger generations that have grown up online amidst an era of waning trust in traditional religious, political and media institutions, the journey of self-discovery becomes highly individualistic rather than collective. Like the characters in the show, a central tenet of Gen Z is an emphasis on self-expression, especially via permanent and non-permanent identity statements.

Look no further than the show’s aesthetic of face tattoos, cat eyes, nail ‘claws’ and hair dye as manifestations of this cultural ethos. While the cosmetics of the characters are hyperbolic, it does so to hammer home a point. Identity norms — whether that is gender & sexual fluidity or self-expression — have changed at a nonlinear rate.

In fact, Euphoria’s beauty norms are actually less extreme than you might believe. Paired with COVID’s impact on salon and beauty service businesses, consumers are looking to a number of cosmetic products as a means of self-expression. The growth of artificial nail products is one such example.

Tattoos are another. Tattoo culture has particularly evolved in our society from being emblem of affiliation (military units, fraternities, and gangs) to a marker of individuality. As one author puts it, tattoos are “part of the ongoing narrative of the personal myth”.

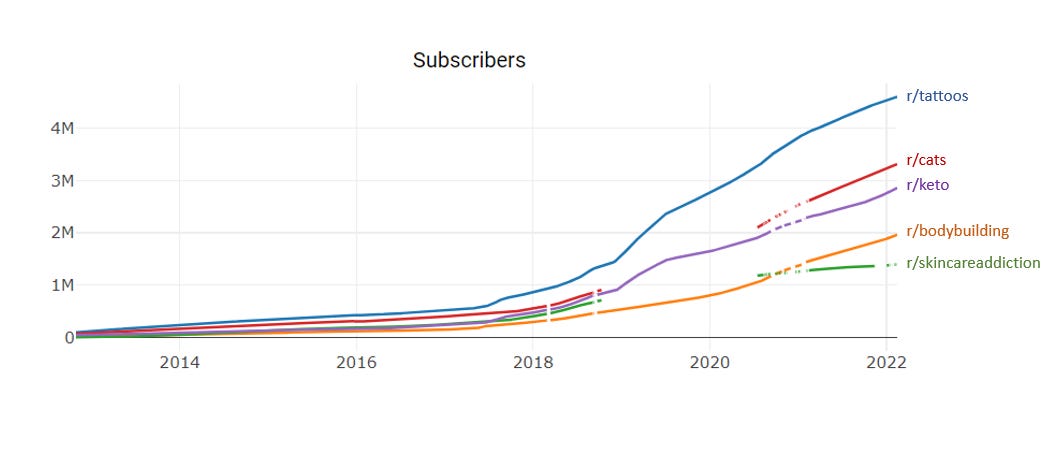

As more emphasis is placed on self-expression and individualism, tattoo culture has become more and more mainstream. Look no further than the size of the tattoo subreddit community, especially compared to other intense sub cultures like skincare, keto and bodybuilding.

Yet, this causes plenty of tension between generations. According to a poll from the University of Michigan, 78% of parents had a clear answer when asked how they would react if their own teen wanted a tattoo: absolutely not.

Nonetheless, data from Pew Research states that 38% of young people ages 18 to 29 have at least one tattoo.

Permanent and semi-permanent identity objects are a fixture among Gen Z and Millennials who opt for more self expression and reject traditional taboos. Euphoria sensationalizes some of these trends (such as face tattoos) to emphasize this change and create a reaction that most likely alienates older viewers; thereby in the process replicating some of the tension it is trying to abstract.

No longer does the nail that sticks out get hammered down. If you don’t stick out, you don’t fit in.

Sex

Euphoria intertwines sex and identity in a number of means, and actively opposes the traditional American sexual ethics that has pervaded decades. Euphoria blatantly rejects the ‘Their First Time’ and ‘Unexpected Virgin’ tropes that underpin so many 21st century high school features such as American Pie, Superbad, Easy A, Mean Girls and beyond that were particularly popular for older Millennials. While Millennials enjoyed a romanticized relationship with sex, Gen Z’s positioning is more pragmatic. Naivety and virginity are no longer the status quo; agency, promiscuity and fluidity is.

Imagine showing the Euphoria to your parents or — better yet — grandparents. I would venture to say that it would be difficult for them to process. The natural takeaway would be that young adults are more sexually active than ever before.

But that’s actually the exact opposite of the case. Gen Z is less sexually active than previous generations.

In fact, from 2008 to 2018, the share of Americans ages 18 to 29 who reported having no sex doubled. Young people are marrying later in life (if at all) and may be having less sex as a result.

This seems antithetical to the mainstream adoption of ‘sexual wellness’ as a consumer category. As a recent article in Beauty Independent notes —

Propelled by millennials and members of gen Z, the modern sexual revolution has gone beyond the steps the precursor sexual revolution took to push sex into the arena of health and wellness.

Indeed, according to Spate, there are an average of 11.6 million searches for sexual wellness products every month in the US. Retailers like Sephora, Target and Walmart are investing heavily in the sexual wellness category, stocking products from brands like Maude, Cake and Dame that range from sex toys to lubricants.

So we see a strange dichotomy unfold. On one end, there is vast amount of research suggesting that Millennials and Gen Z are having less sex. On the other end, we are seeing an increase in the supply and distribution of sexual wellness brands specifically catered to this demographic.

What gives?

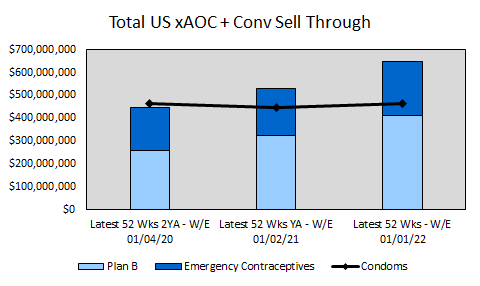

On a macro level, sexual norms are behaving equally as strange. First, condom sales over the past three years are essentially flat — having only grown at a 0.4% CAGR after decreasing in 2020 (most likely as a result of COVID).

But during the same period, emergency contraceptive sales increased substantially. Plan B sales have increased at a 25.7% CAGR(!), while the overall emergency contraceptive category grew at a 20.5% CAGR.

In addition, the pregnancy test kit market has grown at a 13.3% CAGR during the same period.

Indeed, this could be a rational consequence of COVID — people have felt less comfortable starting a family amidst the subsequent financial uncertainty (especially in 2020) and public health concerns so are more inclined to terminate a pregnancy early on.

But emergency contractive consumers generally index much younger. According to KFF, three in ten (32%) women ages 15 to 24 who have ever had sex say they have taken EC pills, compared to 10% of women ages 35-44. Which in conjunction with younger generations waiting longer for marriage, suggests that the increase in emergency contraceptives sales is being driven by younger consumers who most likely are having casual sex and are opting for emergency contraceptives due to less precaution (flat condom sales) rather than a change in family planning.

But let’s double click on Euphoria. First, we know that a core theme — or information input — of the story is sex and sexuality. Second, we know that the show is incredibly popular, which suggests that it communicates this theme in a compelling fashion. So it would seem odd for it to be so off base.

But if you analyze the story’s construction in more detail, you will find that while Euphoria depicts changing sexual fluidity and a less romanticized relationship with sex, sexual intercourse is, for the most part, confined to only a few of the main characters.

In fact, given the rather substantial degree of nudity and sexual circumstances on the show, it is easy to conflate those two for something it is not. Rather, the show deals with sex in two formats — one being the pragmatic depiction of actual sexual intercourse, and the other being the more romanticized depiction of sexualized behavior which lives online in the digital vacuum of nude pictures, messaging, cam recording shows and so on.

It’s an important nuance. It suggests that while for younger generations sexual activity is more fluid, open-minded and promiscuous, they opt to exert their sexuality through new forms of behavior (particularly online) besides actual intercourse.

Generational Tension

I think there are a few forces driving this.

The first is a dramatic change in cultural standards driven by a deconstruction of traditional cultural authority — or where people draw their values from. Historically, individuals’ values (and sexual behavior) have been governed by direct and indirect means. Direct would their parents and family, indirect would be the institutions that govern their parents and family and indirectly govern their behavior due to the social and political influence they maintain.

Indeed, the soft power of the three major social institutions in our lives — religious, political and media — has decreased substantially, and is pretty well documented. No statistic better demonstrates this than the dramatic decrease in religious affiliation amongst Millennials and Gen Z.

But the more difficult, and important, consideration is how the fundamental power of direct influence has changed between generations. Back to the original point of cultural objects, Millennials and Gen Z are digital natives, and have grown up in an age where the values and identity are constructed via online communication and social media networks. This creates a cultural tapestry composed of relatively weak stories that have little nuance, and so who an individual is is defined of many smaller stores of information rather than a few richer ones. Meaning, people’s essence is composed of many things that lend little interpretation rather than fewer things that lend substantial interpretation.

The latter results in a surface area that leads to implicit trust. Having a smaller supply of stories equalizes culture and creates a bridge between different communities and individuals to share something in common. More, since these stories lend themselves to greater interpretation, it allows for more mutual reciprocity: the feeling of both fitting in, and standing out.

Defining yourself based on the stories of Christianity or America or even Star Wars opens the door for more mutual reciprocity than does defining yourself based on the aggregate stories you consume on social media.

Consequently, there exists a fundamental breakdown in intergenerational communication. Asking a 20 year-old her favorite movie might not store as much information as asking a 20 year-old the same question two decades prior would have. The better question today may be who is your favorite Youtuber or Instagram account — and perhaps this stores a relatively sound amount of information, but it becomes less fungible across generations. It’s really difficult for a 40 year-old to evaluate an individual based on that information.

Furthermore, distributing stories via traditional linear rails meant that geography was the main predicator as to which stories an individual would interact with. Grandparents and teenagers alike were shown the same movies at the theater, the same news in the paper, the same books in the library, and the same shows on cable television. This caused natural collision between individuals (and generations) with varying interests and social circles, and in the process led to the serendipity of unlike-minded individuals finding common ground.

But in the world of algorithmic distribution, the stories you consume are preordained. You are recommended stories based on what people just like you have watched, or see content that your friends and favorite creators have published. This creates an echo chamber where likeminded people see the same weak stories, which heightens the divide between different social and cultural groups and prevents any form of serendipitous collision, while stymying cross-generational and cross-ideological interaction.

(This, I believe, is what leads to such pervasive trolling and shit-posting online. Within these bubbles of sameness, the evolutionary rules of natural selection takes over and individuals thrash to find any nuanced expression to standout, even if that means succumbing to more base and crude behavior.)

Thus, there is really no standard unit of cultural account. The stores of information, the stories that define us, are no longer fungible — a movie no longer holds the same relative value as it once did and the objects that capture younger generations’ stories (Tik Tok, YouTube, Roblox) are foreign to older generations. It’s almost as if we no longer can transact with each other with the same currency.

This causes friction between generations and makes it difficult to communicate and pass down cultural values. So, there is this inherent lack of trust young people have of older generations, so their cultural norms — whether it relates to sexuality or something else — holds less weight and no longer fit the rational framework of the subsequent group.

Closing Thoughts

We no longer have three TV stations that distribute the same stories and have an outsized influence on culture, where individuals can build trust and discourse based on their interpretation of the stories that underpin many of their essence.

There perhaps has never been a more pronounced generational gap than between Millennials & Gen Z and that of their parents/grandparents. With that comes a bit less trust, mentioned for the reasons above, but I also believe there are other elements at play that lead to other breakdowns of trust.

Millennials and Gen-Zs have been the first adopters of many consumer technologies that have become the core driver of economic value writ large. This is a generation that has asymmetrical skillset advantages in terms of their technological literacy and adoption of the main drivers of economic value today, but receive none of the economic opportunity. They call bullshit that older generations hoard all the financial wealth but none of the cultural capital.

As my friend Rex Woodbury noted, younger people recoil from the path their parents and grandparents followed. One 23-year-old woman put it this way: “There’s this underlying resentment because our parents were able to have a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio and be fine and retire with no worries at all. But that’s not the case for this generation.” We see rejection of past norms in the shift away from credit toward debit, in the 50% of Gen Zs investing in crypto, in the rise of freelancing. (One wild stat: more than a third of Millennial millionaires have at least half their wealth in crypto and about half own NFTs.)

This is where Euphoria does a tremendous job. I believe the most valuable interpretation of the show and its stylistic and narrative decisions is its underscoring of this generational tension. Said another way, Euphoria presents the input information we have discussed in such a sensational and exaggerated way to abstractly emphasize the generational tension that exists in our society today — specifically around issues like self-expression and sexuality.

For example, the trauma that underpins Euphoria is recounted through Rue-narrated flashbacks about the characters’ parents and the many ways in which they’ve ultimately caused harm to their children. It’s not direct harm or abuse, but indirectly through previous life decisions; parallels which can be drawn to the inter-generational strife we see today given issues like economic inequality, racial injustice and climate change.

Look at the evolution of Cal’s character in season 2. With it, Euphoria unpacks the nuance of its leading antagonist (Nate Jacobs) who is haunted by his father’s sexual behavior. But, his father ultimately behaves in such a way because of the social ostracization that existed for homosexuals coming of age in the ‘90s.

Ultimately, Euphoria is extrapolating the worldview of this generation, a cohort that grew up amidst the Great Financial Crisis and are the first to mature in a period that treats climate change as legitimate rather than a speculative threat. This is a group that doesn’t trust traditional institutions like religious bodies, the government or mass media, and are left with less economic opportunity and heightening environmental insecurity because of the actions of those that came before them.

To me, it suggests a fundamental change in the risk aversion of an entire generation. Younger generations are more comfortable with risk, especially if the risk is realized somewhere in the future because there is a greater discounting of the future. I think you see this play out with the step function change in emergency contraceptives sales while condom sales were flat — sexually active young adults are willing to take on more risk when they have sex. You see this in the labor markets, with young adults willing to resign and leave jobs quicker, and with self-expression, with young adults willing to make bolder beauty statements, some of which are permanent in nature (tattoos). And you see this in their investing in crypto and the rise of get-rich-quick stonks like Gamestop and AMC in the public markets.

As technology and innovation compounds and progress accelerates, volatility increases. So, perhaps the risk calculus of the status quo must change with it; more progress actually creates more risk as systems become more complex and technology heightens the power of the individual in a network structured for top down governance. It’s an interesting thought experiment, and I don’t know the answer. But what I do believe is that there are clear signals that younger generations are comfortable with more risk; how does that play out when they begin to age into their peak earning years and accumulate more societal wealth? It will be interesting to see how their worldview affects capital allocation and social, political and economic activity in the future.