eCommerce is Dead, it Just Doesn't Know it Yet

Native vs. Skeuomorphic innovation, lessons from Gaming, and the future of online commerce

The future is extremely difficult to predict—but there are clues. Looking at the trend line of progress and where it's pointing, this post will try to build towards the future of digital commerce.

By all indications, the world continues on an inevitable march from the analog to the digital.

But within this paradigm shift, there exists a fascinating delta: while internet usage has become nearly ubiquitous, only a fraction of our GDP is online. On Patrick O'Shaughnessy’s Invest Like the Best podcast, Ram Parameswaran provides three methodologies for quantifying online GDP. While the definition of what exactly entails an ‘internet’ company is quite muddled, as technology — specifically software — has permeated into nearly every industry, the thinking is directionally correct.

[First], total earnings today of internet companies as a percentage of total earnings globally is between 5% and 7%. This is net income of internet companies divided by total earnings globally.

Secondly, the volume that is sent through the internet is still in the mid-single digits right now.

And number three is if you look at the market capitalization of internet companies as a percentage of total global market cap, it's around 10%. So all by any definition, we're so dependent on the internet right now, and yet, even today, less than 10%, by almost any measure is still conducted via the internet.

Synthesizing Chris Dixon’s thinking on skeuomorphism, this post will create a framework to look at how two types of innovation —skeuomorphic and native — enable digitization and online GDP growth. With this in mind, I will examine the taxonomy of today’s eCommerce paradigm, taking lessons from the gaming industry to show how the current model is not built for the future.

In sum, this piece will outline:

A framework for skeuomorphic vs. native digital innovation

What gaming has taught us

Closing Thoughts / A Bridge to the Future

*Note: I use the term skeuomorphic to describe online replicas of offline business models and services. It is important to distinguish this from the design concept of skeuomorphism, which is used to describe interface objects that mimic their real-world counterparts in how they appear and/or how the user can interact with them (think “trash can” for discarding items). While many forms of native innovations leverage skeuomorphic design (like avatar ‘skins’) to make them more accessible and intuitive to users, they are completely novel creations that are intrinsic to the internet and digital realm.

A Tale of Two Innovations

There are two types of digital innovation: skeuomorphic and native.

Skeuomorphic innovation takes things from the offline world and puts them online. Skeuomorphic innovation unlocks the benefits of the internet’s scale, enables digital coordination and distribution layers, and often leads to a 10x better consumer experience.

Native innovation creates novel services, products, businesses, industries and economies that are intrinsic to the internet and are impossible to replicate offline. Native innovation directly sits on top of, and captures the value created from, internet primitives. Primitives are foundational technologies or protocols that enable more complex systems to be built on top of it. Primitives are the building blocks of the internet.

As Chris Dixon notes, the website is a digital primitive — as is the HTTP and SMTP protocols. Social networks and search engines are forms of native innovations born from digital primitives. Consequently, companies like Facebook and Google have emerged as two of the most valuable internet companies in the world.

Native innovation causes nonlinear growth of online GDP and enables new ways to interact with the internet. Thus, it both pulls GDP from offline to online and creates net new digital services and products, leading to positive sum GDP growth.

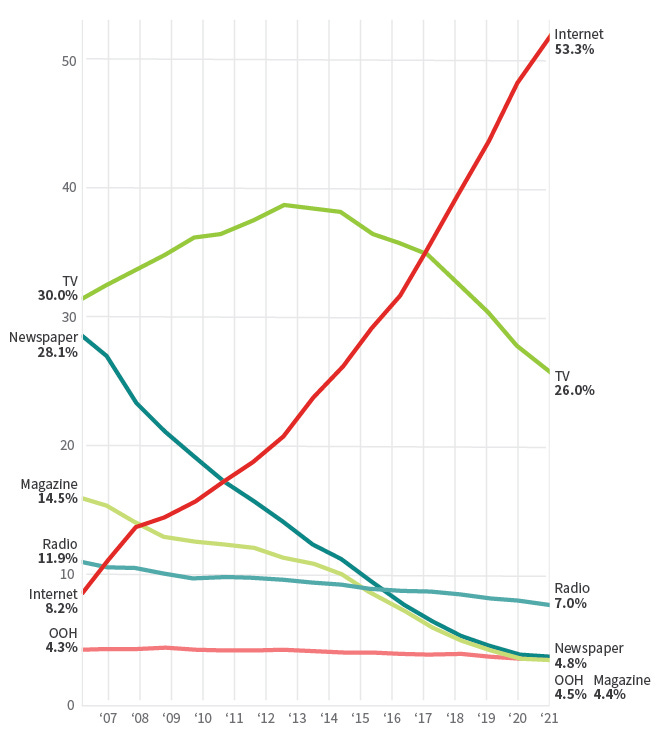

But perhaps most importantly, native innovation enables new forms of skeuomorphic innovation. Search engines and social media networks created novel forms of digitally native categories and careers, new means of monetization— namely digital advertising— and enabled a new era of skeuomorphic innovations that depended heavily on third-party demand aggregation (like eCommerce).

Overtime, the compounding nature of native and skeuomorphic innovation will be the driver of online GDP growth.

eCommerce = Offline Retail, but Online

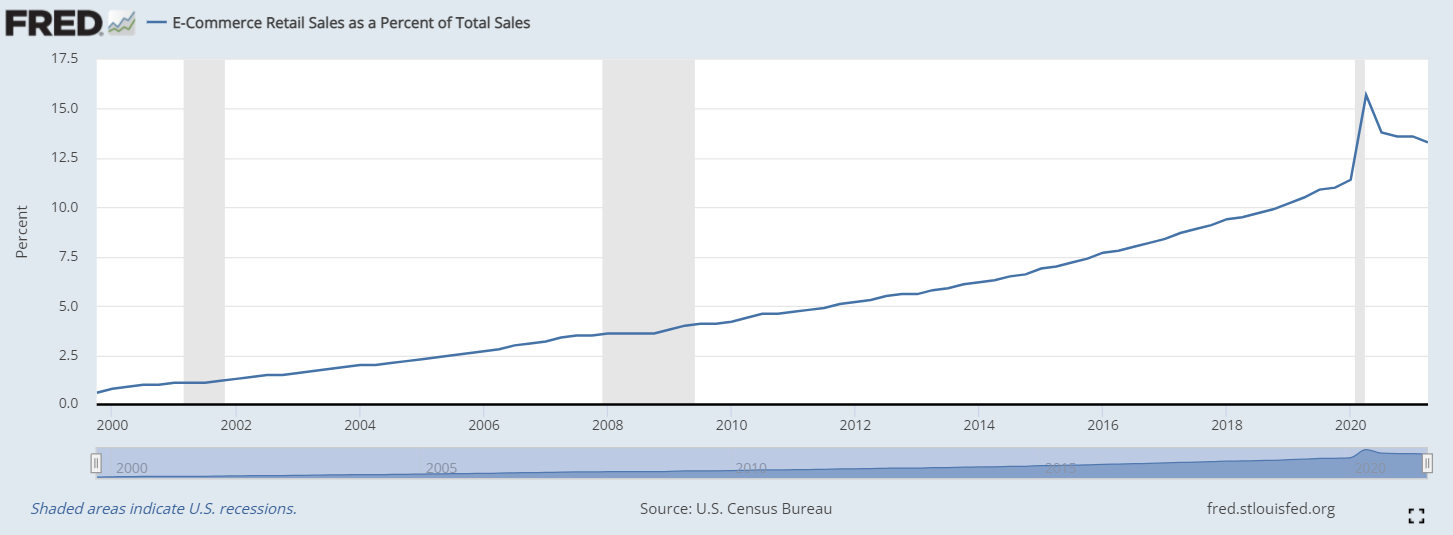

eCommerce is a form of skeuomorphic innovation. Third-party marketplaces like Amazon and first-party enablement platforms like Shopify have digitized shopping. Although digital, the experience is largely still the same as it’s offline counterpart — you visit a (digital) store to buy a physical product. As such, eCommerce retail sales as a percent of total sales is still quite immaterial (<15%). And while COVID-19 has proved to be an accelerant, growth is still rather linear.

Yet, this is counterintuitive. 263 million American consumers shop online—some 80% of the population. More, most consumers’ buying journey begins online, with 55% doing research online when planning a major purchase. This is further reinforced by a Think with Google Study that shows 66% of shoppers prefer online shopping to find items they are looking for, compared to 27% who prefer to search offline. And online shoppers are in demand of new products constantly. In fact, 75 percent of consumers’ search queries each month are brand new.

With all that in mind, shouldn’t the eCommerce growth curve look more like digital advertising (powered by native innovations like search engines and social networks) and lead to nonlinear behavior?

The reason it hasn’t is because the vast majority of online shopping today is simply a digital replica of its offline counterpart. In fact, consumers who prefer online shopping do so because of how convenient it makes an offline service: delivery. 60% of consumers cite direct home delivery as a the primary reason for shopping online. Yet, direct home delivery is nothing new — nearly 30% of milk sales were delivered to households in the 1960s.

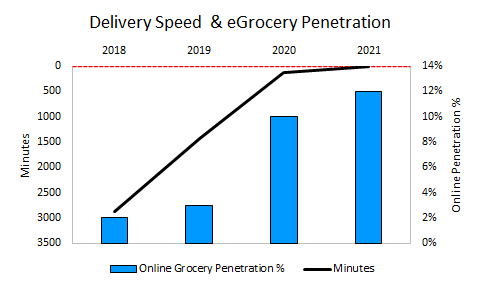

Interestingly, delivery has become a major target for innovation within the category, with companies like Jokr and Gorillas raising billions of dollars to offer near-instant (<15 minute) delivery.

While these business models are trying to smooth out the frictions of the today’s skeuomorphic reality, they are working towards an impossible future state and ultimately a dead end. Delivery will never be zero (or sub zero), and the power laws have mostly been accounted for.

More importantly, no matter how convenient delivery becomes, the consumer has demonstrated that 10x better doesn’t unlock nonlinear growth.

For example (and this is surface level analysis), reduction in delivery speed from 1 day to 15 minutes is theoretically a 96x better value prop. However, this change only resulted in a 6x growth of eGrocery penetration (which was also inflated due to the offline channel being shut down). In this case, 10x better leads only 0.63% incremental growth.

Again, 60% of consumers cite direct home delivery as a the primary reason for shopping online, and 80% of Americans shop online (50% in the case of grocery). Thus, shouldn’t a >10x improvement to the primary source of utility of a widely adopted behavior lead to nonlinear take?

When you boil it down, the thesis is the same as traditional grocery stores: razor thin margins with massive startup costs (capital moats) that depend on tremendous scale. As such, when skeuomorphic in nature, 10x better does not always equal nonlinear behavior.

This is not to say that skeuomorphic models cannot be great businesses and phenomenal outcomes. Rather, in the long run, online businesses built on top of skeuomorphic principles will not drive online GDP growth.

eCommerce, as constructed today, will become legacy and will not be the paradigm of the digital commerce of tomorrow. Rather, it will look radically different.

The gaming industry could provide a blueprint.

Lessons from Gaming

Historically, the gaming and CPG industries looked a lot alike. A product was manufactured in a standardized format, sold to a retailer, then distributed to a consumer. Then came the internet, which enabled the distribution layer to be digitized.

At first online gaming was built skeuomorphically. Games were play-only and sold in the same atomic unit (game) according to outdated standardized formats. As such, LTV was capped to the purchase price of the product, publishers had limited-to-no visibility of who their consumer were, and their unit economics were burdened by vast marketing expenses and high take rates from distributors (which still exists today). Not much had changed.

However, new players, specifically Roblox and Fortnite, began to rethink how gaming leverages digital primitives. Similar to how websites could be read/write, games could be play/write and enhanced through user-generated content. The atomic unit no longer had to be the ‘game’, rather nearly every digital good within the game became composable and exchangeable. This completely flipped the gaming model on its head and enabled the free-to-play model to take off at scale. A free-to-play model allowed companies, rather than charge a single price, to calibrate a user’s payment based on their level of intensity. LTV was no longer capped at $60, but became theoretically limitless.

On top of this, this model enabled sophisticated microeconomies and social layers that connected to a larger digital meta-game. The meta-game provides an abstraction layer above a ‘game’, thereby creating new elements of identity and social status. The new gaming model permitted a sense of community above the gameplay, which provides a constant meaning as the context within the game changes.

The consequences of this were profound. Look at Roblox, for example. About 80% of U.S. kids age 9 to 12 have played Roblox, with headlines like this underscoring it’s engagement: “Young People Spent More Time on Roblox than YouTube, Netflix and Facebook Combined.”

This model enabled novel monetization formats and digital experiences— in-app purchases, in-game ads, expansion packs, season pass, limited edition skins/costumes, etc. Games like Roblox and Fortnite have pushed forward the virtual goods market, which is now worth ~$60 billion and on track to be worth ~$200 billion by 2025.

A decade ago, in-game micropurchases made up 20% of gaming revenue. Today, they make up 75%. By 2025, they’ll make up 95%.

Micropurchases have fueled the gaming industry’s nonlinear growth, which has greatly outpaced other entertainment industries whom, for the most part, replicated their offline businesses by digitizing the distribution layer in the form of streaming.

A Look Inside Roblox

Roblox has developed a game creation platform that supports user generated content and ‘social gaming’. Developers create “experiences” (or games) and/or virtual goods for the players. Monetization occurs when some users buy Robux (fungible token) to pay developers for an experience or virtual items (non-fungible tokens) for their avatar (identity layer). This creates a network effect as players receive more social capital from their virtual cosmetic items if it is seen by their friends (and they also want to play alongside their friends), attracting more users (community), which attracts more developers to create additional content. (Interestingly this developer-first model looks a lot like Shopify’s).

What’s fascinating is that within this flywheel Roblox has created complementary network effects between experiences and virtual items.

“Complementary network effects” refer to situations where a product gets more valuable as more people use the product’s complement(s). Two products are complementary when they are more (or only) useful together – for example, a video game and video game console, or an OS and an application for that OS.

As more users play a certain game, the value of a virtual item specific to that game increases. For example, if a game that involves digging explodes in popularity, the value of a virtual shovel increases. Inversely, if more users are purchasing virtual shovels, developers will be attracted to create games that utilize that item.

However, Roblox dictates the liquidity of these markets, and regulates what items are allowed to be resold.

“Right now only an account with a membership can participate in private selling. Additionally, as with trading, only items marked as Limited or Limited U are able to be sold. If an item is Limited or Limited U, there will be an icon declaring it as such underneath the item's picture when viewing its details page or when browsing the catalog.”

Source: Roblox

Roblox internalizes these network effects and prevents price discovery and market making. Roblox only allows players to resell their items based on the original purchase price, rather than the current market price. Additionally, Roblox takes a 30% transaction fee from these trades. As such, users struggle to convert their social utility to financial utility.

A Better Way

The rise of Gaming-as-a-Service platforms serve as an interesting case study for the future of commerce. Composable atomic units, microeconomies, connecting to a meta-game focused on identity and social status, variable reward mechanisms, etc., are all relevant elements. Gaming leverages fungible tokens (VBucks, Robux) and non-fungbile tokens (skins, passes, cosmetics, emotes, etc.) to create a sophisticated internet-native economy.

But, current game design is a trojan horse for what can be. Companies like Roblox and Fortnite create the allusion of scarcity and ownership. In reality, users have no control over the market supply of virtual items, and rent, rather than own, the virtual goods.

Moreover, users’ social status — and thus participation in the meta-game — is confined to each individual game, rather than the internet at large. As such, users take on all of the platform risk without benefitting from their contribution to platform growth. Meaning, if Roblox ceased to exist tomorrow, all of their users’ social capital accumulated via virtual goods would be destroyed. Inversely, early adopters of certain experiences or goods do not benefit from potential financial upsides if they gain in popularity.

NFTs and new digital primitives powered by blockchain protocols present a better way. Blockchain tokens — fungibles and Non Fungible Tokens (NFTs) — are digital primitives that give users ownership of digital items, which they can take from one place to another. If Roblox decides to increase their take rate, a user could take their digital goods (and social utility) over to a new game. If a user purchases a limited edition skin from an up-and-coming developer that has inherent scarcity, that user can liquify the social capital into monies (Ethereum) at any time. The use cases and unlocks of web3 are far more extensive, and I will dive in in greater detail in the following posts.

Closing Thoughts

Faster Delivery is a dead end. Digital marketing is a dead end. Even on a macro level, as they stand today, Shopify and Amazon are legacy businesses — they just don’t even know it yet.

We are becoming digital beings. GDP will continue to move online. For commerce to be be a driver of substantial online GDP growth, it will not look like it does today.

Rather, native innovations built on top of new primitives like NFTs will lead to completely novel forms of monetization that redefine the ways the cash register rings in the industry.

These web native innovations will be powered by primitives that enable creativity and production that can only exist online. DAOs and NFTs are just some of the new digital primitives enabled by Web3 that I believe will be used by the next wave of native innovations that unlock truly incremental, nonlinear growth. NFTs enable digital ownership, scarcity and composability. These are features that may allow brands to, for the fist time, liquify the social capital derived from brand equity.

Similar to the trajectory of the gaming industry over the past decade, where virtual cosmetics went from 20% to 75% of total revenue and the category grew from $67B to $200B in revenue, so too will these primitives usher in a new wave of digitally-native consumption.

The future of digital commerce will adopt similar design construction that has pervaded across social networks and modern gaming platforms, such as connecting to a meta-game, variable reward mechanics, frequent feedback loops and identity.

The atomic unit will move beyond a physical product, and new microeconomies powering various types of micropurchases will emerge in multiplayer shopping.

For example, expect digitally native virtual brands that are produced, distributed and consumed completely online and portable across the web.

Consequently, the future model must allow consumers to create value for themselves given the tools that brands can provide (the product being just one of them), rather than solely extrapolating value via a single point of consumption.

eCommerce as we know it is dead, it just doesn’t know it yet.