Part 2: Bored Ape Yacht Club is, in fact, Boring

Fandom does not follow billion dollar valuations, billion dollar valuations follows fandom.

Quick programming note

I’ve been working on this post since April 2022 (it was titled ‘The Impending Bored Ape Yacht Club Bubble Burst’) when I began my investigation into ‘what makes IP valuable’. I think I owe it to you and to myself to complete the train of thought here, so before digging further in to the future of commerce, I want to close this thread.

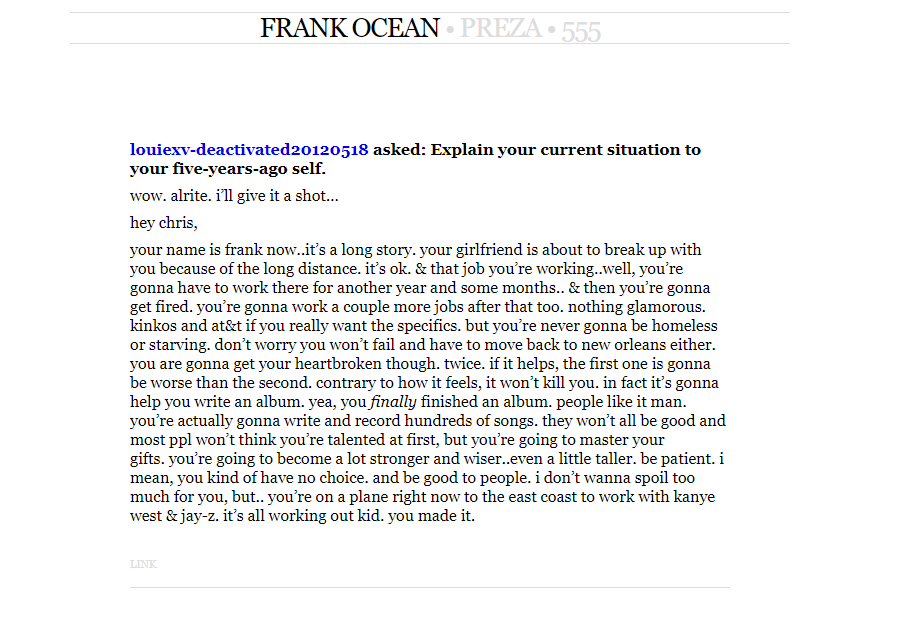

There is no Frank without Chris

In a letter posted on Tumblr, Frank Ocean seeks to explain his current stardom to his five-years-ago self. As Frank writes:

While Frank’s letter seeks to rationalize his fame, it also succeeds at explaining the process that leads artists like himself to eventually create valuable IP.

Frank, then known as Chris, started out like all IP creators by producing common property outputs that were commercially worthless to everyone else besides himself. They were worthless because they didn’t create entertainment utility for fans, but were valuable to Chris because he enjoyed the process of improving.

Through the act of producing these common property outputs, Frank accumulated skillset and a proof of work that compounded. In Frank’s own words to himself he reveals as much:

You’re actually gonna write and record hundreds of songs. they won’t all be good and most ppl won’t think you’re talented at first, but you’re going to master your gifts.

Indeed, only the IP creator has the insight to get to mastery as each song and production run builds atop of the other, and only the IP creator has the incentive to go through the reflexive process of becoming “a lot stronger and wiser”.

As Frank notes to himself, “you kind of have no choice”. The incentives are different for everyone else besides himself; he is the only person who gains value from the process of Chris Ocean becoming stronger and wiser and eventually reaching a skill level that allows him to produce music that fans find entertaining.

Moreover, only the IP creator has access to their imagination and emotions, often provoked from life moments like getting your heartbroken and fired all at once, as Frank reveals, an intrinsic experience that makes them uniquely skilled to produce a specific entertainment product that delights fans.

In short, Frank Ocean’s IP has value because I and millions of other ordinary people love his music. I love his music because it’s highly differentiated. It’s highly differentiated because he spent years producing songs that were worthless to everyone else but Frank (who was Chris at the time), yet he persevered during the purgatorial ‘No Man’s Land’ stage because he gained intrinsic value from building his skillset and growing as a musician. More, he was able to pair that with a unique set of life experiences that made him even more differentiated.

Why does Frank do it? As I wrote in What Makes IP Valuable?

He does so in order to reach a level of skill and scale to produce an MVIP that could unlock distribution and monetization potential, and which potentially bootstraps future intrinsic product distribution — i.e. publishing Harry Potter & The Philosopher’s Stone or making it to the NBA or signing a record deal.

The only way to accumulate the necessary skill and scale is through the centralized production of CP outputs, and the producer gains value from the process of getting better.

But, over the past two years, I believe this model has gotten lost amidst the enthusiasm of decentralized IP ownership.

Projects like Bored Ape Yacht Club believe it can create valuable IP by producing a singular object (like a PFP) and then selling the ownership of the object based on the potential of the “IP”. It assumes that IP value can be reverse engineered, that you can start with Frank Ocean without having Chris, and more importantly, bypass the incremental transformation of Chris.

Instead, the hypothesis believes that by creating a liquid market and supply scarcity, a project can skip the painful process of bootstrapping a fanbase and finding product-market fit.

This post will synthesize the learnings from Part 1 to outline why I believe this is a fundamentally incorrect understanding of IP production and value creation.

My intention is not to kick crypto while it is down, but rather investigate a consensus. Indeed, part of me is concerned that the original goal of this post — providing a dissenting position to the prevailing consensus thinking— will implicitly be diluted now that the consensus has changed. But nonetheless, hopefully the ether proves strong enough to keep its bite amidst the tonic, and I want to speak honestly on what I’ve observed.

Conflating Luck for Skill

I’ve attended Bored Ape Yacht Club and NFT parties in NYC, LA and Miami. The owners of Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs that I met came from a myriad of backgrounds — I met many real estate agents and lawyers, a few designers, a dash of finance bros.

Very quickly, these individuals accumulated a tremendous amount of wealth and social capital. Why?

They were lucky.

They rode the market beta and speculated on a cool looking project. From then on, the vast majority of them did not produce any outputs that directly contributed to the exponential growth of their IP, they just rode the wave. When asked what they did, the prevailing responses were either:

I’m an NFT collector

I’m a crypto influencer

They were not producing intrinsic products or building a skillset that helps differentiate their IP.

The market, in a state of euphoria, confirmed this behavior. Owning a BAYC became a sign of prestige, a credential that you had the skillset to create valuable IP.

Others in the space began to pay these BAYC owners to promote their own projects. In return, BAYC owners received the projects’ NFTs for free or at a substantial discount, and then sold it upon the pump. Thus, this influencer-like social capital was essentially a dividend for owning BAYC, which they were able to liquify in other monies like ETH or USDC.

As the price of BAYC went up, so did their social capital. More projects wanted their endorsement and were willing to pay even more for it, and on and on it went.

This is not to say that this was the prevailing behavior across the entirety of BAYC owners. But the anecdata that I, and many others, collected is too meaningful to ignore.

However, what I find more interesting, and more important to dissect than this behavior, is the mental models that allowed for these individuals to gain prestige and wealth in the first.

This mental model was adopted at a rapid pace, fed by astronomical price appreciation, that fundamentally failed to explore what makes IP valuable. Instead, it conflated luck for skill and created an entire discipline of speculators that thought themselves artists, storytellers and the next great ushers of IP.

Why is this important?

Because they are wrong.

Creating valuable IP is not a game for mercenaries, it is a game for the wounded.

There is a reason why the starving artist trope exists. To be an artist, at first you must starve — hopefully not literally, but suffering is unavoidable. Your suffering is the cost of your art.

Wandering your imagination to tell a story with the depths and emotion of Harry Potter, or Game of Thrones, or Lord of The Rings requires brutal introspection, an offensive degree of self-absorption and utter obsession to an imaginary world that for years only you are crazy enough to believe should exist and only you are willing to take on the opportunity cost to make it so.

I’ve tried it. It’s lonely. It’s costly. It’s irrational. But to create great music, to be a great athlete, to write a great story, to be a great founder, it’s unavoidable.

It is not a get rich quick scheme. Those short cuts are littered with the corpses of one-hit wonders who created a product that found product-market fit with a group of fans, but never invested in the continued process of production that incrementally saw their skillset and differentiation improve.

In his GQ exclusive on Yuga Labs and Bore Ape Yacht Club, Will Stephenson unearthed a number of pertinent quotes and observations that prove helpful guardrails to frame this analysis.

Yuga Lab’s CEO, Nicole Muniz, who formerly worked in brand development for Google, told Stephenson —

“We think of Otherside as a digital Disney World.” The difference being, of course, “the platform is designed to allow anyone to build their own ‘rides’ or ‘attractions’ in this metaverse and own the value of those for the community.”

Disney World was made possible because of the decades Disney spent producing intrinsic products — stories like Cinderella, Mickey Mouse, Snow White and more — that entertained millions of people and built a fanbase. Once the IP reached a critical mass of fandom, Disney was able to decentralize production to other producers who create distributed products (like Disney World) that only exist because of this fandom.

I struggle to find evidence that consumers who do not have ownership interest in BAYC desire the products that have been produced thus far, or have any affinity to the IP beyond its financialization.

Take their foray into music for example. The prevailing consensus accepts that that price of a BAYC NFT dictates that the IP has substantial value and thus can now enable new types of supply — distributed products — that leverage the underlying IP via Bored Ape music projects. From Stephenson’s piece:

Timbaland had started his own company called Ape-In Productions, which would host a roster of Bored Ape musical projects. (Its first was a hip-hop group called TheZoo, whose debut single, “ApeSh!t,” Timbaland produced himself.)

Yet, the underlying BAYC IP has failed to bootstrap a meaningful fanbase that affords the production of distributed products. It has failed to bootstrap a meaningful fanbase because it hasn’t produced any intrinsic products. It is simply a PFP.

As a result, there is no demand. As you can see, the video only has 152k views over 9 months and the Ape-In Productions Youtube channel has 1.35k subscribers. Another AIP song ‘Take Off’ has only gathered 600 views in 6 months. Timbaland, on the other hand, has 1.97M subscribers and nearly all of his songs have tens of millions of views.

Since the underlying BAYC IP lacks a substantial fanbase, the only factor that will dictate the success of Ape-In Productions is it’s intrinsic product: the quality of the music. Yet, from the jump, it severely limits the potential of its distributed producers like Timbaland.

This is because the project creates artificial guardrails on Timbaland’s differentiation as a music producer by forcing him to pander to a creative output that is set in place by a pre-product market fit IP (BAYC), rather than based on what his existing fanbase knows and loves.

Universal’s new Web3 Label, 10:22PM, is taking a similar approach. Celine Joshua, the Universal exec who founded the blockchain-based label and the mind behind Kingship, describes the project as the following:

“Kingship is an access token. It’s going to provide value and utility—to have the best of every part of the supply chain, physical and digital. […] But there has to be an infrastructure, an architecture, that is truly blockchain native. There has to be a token.

[…]

I think the important thing here is that if you’re a holder of a Kingship NFT, I hope that you fall in love with the music too, but there’s also going to be value built in, in case you don’t.”

What Ape-in Productions and Kinship fail to realize is that failing in love with the music is the means, not the ends. Joshua insists that “there has to be an infrastructure, an architecture, that is truly blockchain native. There has to be a token.” Yet the only thing critical to the success of the project is the one thing that she seems to deprioritize: if potential fans fall in love with the music.

Two months ago, Kingship released a behind the scenes reveal video with Hit-Boy and James Fauntleroy for their song “Rider”. It has 919 views as of writing this. Kingship’s channel only has 120 subscribers. Its most watched video, the aforementioned “Rider”, has 4,919 views since it was released in August.

Clearly, the affiliation with BAYC or blockchain architecture that Joshua speaks of does little to impact the success of the project or create value in case people don’t fall in love with the music. In fact, it does the opposites. I would argue that it hurts the IP value of distributed producers like James Fauntleroy and Timbaland that mistook price for value, and in the process took their attention away from producing music that would entertain their existing fanbase and acquire new ones. By doing so, they lose trust.

Joshua goes on to say:

“When I saw what Yuga created and that they provided the I.P., I looked at it as a decentralized Disney,. It’s a project that launched 10,000 units, that created billions in valuation, and a fandom that will rival some of the biggest recording artists in the world.”

Joshua effectively sums up the fatal mistake that underpinned the fervor of the hype cycle: price and value are not the same thing.

There is a difference between creating billions of dollars in valuation and creating billions of dollars of value.

IP value is created by producing products that entertain fans with no ownership interest in the IP. Yet, BAYC has not done so. Joshua concedes as much when she notes “a fandom that will rival some of the biggest recording artist in the world.”

Which brings up Principle #4:

Principle #4: Fandom does not follow billion dollar valuations, billion dollar valuations follows fandom.

If fans don’t like the music, there is not going to be value built in, as Joshua claims. Value follows product-market fit (musicians making music people enjoy), not from leveraging IP that has a high floor price because of scarcity and momentum.

Jenkins the Valet

You see similar dynamics play out elsewhere. The team behind Jenkins the Valet has sold a set of “writers room” NFTs that allow other ape owners to cast their own avatars in an upcoming book. These owners, in turn, are writing their own backstories, and they held improv sessions in character on Discord to govern the shape of the IP and decentralize both the production and ownership of the intrinsic product (the book).

But these ape owners are financially incentivized to look after the interest of their asset, not the story. More, the story becomes only as good as the backstories written by individuals with no proven skillset in doing so.

In aggregate these collective decisions and incentives grossly subordinate the interest of any mainstream fandom at the expense of the individual IP owners whom are not all clearly aligned. JK Rowling did not have to worry about Hermione and Harry competing for plot lines.

In fact, Neill Strauss, the author hired by the Jenkins the Valet Writers Room, admits as much:

“It’s a great solution for lazy writers, because in a sense you outsource the decision-making process.”

It’s shocking how self-unaware this is to me. Do you think JK Rowling or Stan Lee wanted to outsource their decision making process when they were creating Harry Potter and Spiderman IP? Do you think Michael Jordan wanted a solution to help him be more lazy?

Moreover, do you think Neil Strauss, who “doesn’t own an ape himself “ because “[he’s] really risk averse” and will be taking his paycheck in U.S. dollars rather than Ape Coin or ETH, will put in the hours necessary to accumulate the skill and scale to produce a story that will entertain fans?

Did Michael Jordan not devote everything is his life to the success of his basketball career? Did JK Rowling not bounce from home to home as she obsessively reached into her imagination to tell the story that only she, as the owner and originator of the IP, could tell?

But Jenkins the Valet has no other choice. Since IP ownership is distributed, the owners don’t necessarily have the skillset to produce the products that should have made the IP popular in the first place. As result, they outsource production to individuals like Strauss, who haven’t gone through the compounding process of producing common property outputs that eventually form the IP over time, and have perverse principal-agent incentives.

Which begs the question, why Strauss? Why did Jenkin’s the Valet settle on an individual who is most famous for being the author of The Game, which popularized pickup artistry for the masses, and who ghost-penned the biographies of Jenna Jameson and Marilyn Manson?

The simple truth is that any author worth their salt has no interest in selling the governance and ownership of their IP. They understand that only they can tell the story in a manner that maximizes its potential of product-market-fit, and any distribution of ownership or production adds friction and incentives that oppose that.

Strauss has publicly demonstrated that he is content to outsource his creative process and has no interest in taking equity in the project he is effectively acting as CEO for. As I write this, does this not seem like the fodder for the “How did we miss this?” post-mortems that fed media outlets for weeks after FTX’s collapse?

Strauss seems aware of this potential reckoning. From Stephenson’s piece:

[Strauss] hoped to finish the novel by the end of April but seemed unsure about even the most basic aspects of its structure, or about its potential appeal to those outside the community itself.

Closing Thoughts

IP value is not created through new ways of financializing media objects, but through the continued production of ‘Common Property’ objects that at the moment of production, are perhaps worthless, but soon snowball and compound over time to enable a new type of product that can be distributed to consumers.

For many of the great writers, artists and athletes, it is not the financial upside, but the journey along the way — the climb — that shapes the future successes. If you try to distribute ownership prior to that point, you will introduce friction that dilutes the future vision that one would be speculating on, while also robbing the IP owner from the intrinsic value they receive from ‘the climb’.

Indeed, these moments are often reflected on afterwards with nostalgia and awe, a thread of folklore that we collectively return to to prove the mortality of the IP creator once they have ascended Mount Olympus.

The collective mythos that we create around these moments also reveals another truth: every great athlete, artist, brand and story starts out the same — amateurs that put in work to hone their craft so that one day they can produce something of value.

BAYC, on the other hand, operates under the premise that the price that someone is willing to pay to own an object is what creates durable IP value and product-market fit.

The examples pointed out in this piece demonstrate the importance of producing intrinsic products that build a fanbase. BAYC’s original intrinsic product, a PFP, does not create utility for millions of fans. This is because the form factor itself lacks the robustness to create compelling IP, it is simply a chapter rather than a complete book.

More, because each character was sold off, each being a common property output/part, the Yuga Labs team introduced perverse agent-principle incentives.

As a result, each of these common property outputs conflated their floor price for IP value, and since they didn’t have the skillset — in terms of access to the original IP creators’ imagination as well as tangible creative skills developed through the act of producing IP that finds product-market-fit— they did not produce additional intrinsic products.

Instead, they tried to skip straight to distributing production to other producers like Timbaland and Strauss. Yet without intrinsic products that entertain fans, there is no fanbase, and with no fanbase the distributed products have not been successful.

A Bear Perspective

Eventually, I believe the network of distributed producers, many of themselves mercenaries like Strauss, will become less skilled (as the opportunity cost increases) and less interested as the success of these projects falter. This will cause the rug to be pulled out, as owners of Bored Ape Yacht Club realize that their IP lacks a foundation from which it can become a platform. It is highly likely it will then collapse in onto itself.

This would spark negative media coverage, mostly likely unearthing countless examples of grift, and destroy whatever prestige was left in the brand. The already small pool of fans would diminish, and the project most likely will be left with massive liabilities to network of producers that they have paid to build a “Disneyworld” that nobody has any interest visiting.

BAYC became popular because scarcity and market momentum led to massive price appreciation and made a small group of speculators rich. It has not created any utility for fans via compelling stories or products that have found product-market fit and entertainment value. Instead, external mechanisms have led to the perception of enterprise value, rather than the intrinsic mechanics of distributing intrinsic products that create entertainment utility for a large audience of fans.

NFTs unlock novel potential surface areas that can broaden the scope of who can benefit from IP value. As you can see, fans play a pivotal role, in fact the most pivotal role, so providing fans with mechanism to monetize their contribution is quite powerful. But this must happen after the IP has bootstrapped a sizeable fanbase and cemented its differentiation by producing intrinsic products.

The old tech adage: come for the tool, stay for the network and grow for the status works. The inverse does not.

.