Synthetic Imagination

Engineering autobiographies for AI to create non-consensus breakthroughs.

I. Dreams

The white hill is slowly being swallowed by the viscous, ink-black sky, as if the moon was cracked open into an uncontrollable blowout of crude oil. Immutable, even to that glossy blackness, are the freckles of stars far beyond. Petroleum makeup, it seems, is no match for celestial beauty.

A boy blasts down the face of the hill, his swiftness envy to even Hermes. He is going faster and faster. As fast as light itself. He cranes his head skyward. The stars are no longer twinkling freckles, but refractions of colors that streak the midnight visage like stellar war paint.

His name is Albert Einstein, and we are in his dream.

It is perhaps the most important dream of his life. And, arguably, to mankind. His entire scientific career, Einstein later muses, was a meditation of this dream. It is the dream that served as the inspiration for what was to become the Theory of Relativity. As he describes:

“I was sledding with my friends at night. I started to slide down the hill but my sled started going faster and faster. I was going so fast that I realized I was approaching the speed of light. I looked up at that point and I saw the stars. They were being refracted into colors I had never seen before. I was filled with a sense of awe. I understood in some way that I was looking at the most important meaning in my life.”

Einstein’s dream was far from the only imaginative vision to lead to novel discovery.

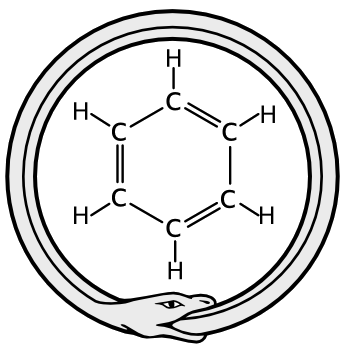

Consider the 19th century German chemist Friedrich August Kekulé, who famously discovered the ring structure of benzene after dreaming of a snake swallowing its own tail.

Or Niels Bohr, the father of quantum mechanics, who in 1922 won the Nobel Prize in physics for the Bohr model of the atom — a model he says came to him in a dream, electrons spinning around a nucleus like planets around the sun.

Or Dmitri Mendeleev, who developed the periodic table after dreaming that all the elements fell into place as required.

“I saw in a dream a table were all the elements fell into place as required. Awakening, I immediately wrote it down on a piece of paper, only in one place did a correction seem necessary.”

Or René Descartes, who in 1619 experienced the “Philosopher’s Dream” while serving in the military, leading him to doubt everything that could be doubted, eventually arriving at the famous "I think, therefore I am" (Cogito, ergo sum).

Or Srinivasa Ramanujan, the Indian mathematician who credited his extraordinary formulas to visions from the goddess Namakkal.

Thus, we begin with an observation:

Breakthrough human ideas (e.g., relativity, benzene ring structure) often originate in imagination — frequently in dreams — rather than through direct, linear reasoning.

And now, a question:

Why did human intelligence arrive to these novel breakthroughs, in fields ranging from theoretical physics to molecular chemistry to philosophy, during dreams?

II. A Construction of Reality

The dreamworld is the realm of imagination. Our mind’s eye, not our senses, produces the information our intelligence processes. We see, but not with sight; we hear, but not with hearing. In dreams, reality is constructed from our ability to produce mental images and generate new “facts” based on one’s imagination.

Imagination draws on two intertwined memory systems:

Episodic memory: autobiographical events with sensory richness, emotional salience, and causal detail.

Semantic memory: general knowledge, concepts, and abstract frameworks.

When integrated, these systems allow the mind to run scenarios that never occurred in the real world — analogies, counterfactuals, and imaginative visions — that often yield more creative insight than direct reasoning.

The uniqueness of imagination comes from the uniqueness of lived experience combined with common knowledge and conceptual frameworks. There is no Theory of Relativity without the sledding hills of Germany; no Cartesian doubt without the existential crucible of military service.

As Einstein himself put it:

“Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.”

A pattern for novel breakthroughs emerges: a deeply personal lived experience collides with stored knowledge to produce imaginative leaps that reason alone cannot summon.

Human progress depends on individuals interpreting the same facts differently. Two people with equal intelligence and knowledge, given the same data, can arrive at radically different conclusions because their lived experiences — the hills they sled down, the books they read as children, the hardships they endured — shape their construction of reality.

This reveals a fundamental truth about human intelligence. We create our own understanding of reality not through objective truth, but through our interactions and communications with others and our own experiences. Sociologist deem this the Social Construction of Reality.

Our experiences filter our perception. Sociologist William Isaac Thomas captured this with the “Thomas Theorem”:

“If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.”

Divergence in worldview produces non-consensus ideas, which are essential for paradigm-shifting innovation. Unique lived experience is thus a key input for non-consensus, high-value creativity.

Today’s AI systems are consensus-driven by design. They are trained on overlapping corpora to predict the most probable next token. They can remix knowledge but not originate it in the most novel sense. Modern AI (e.g., LLMs) has vast semantic knowledge but no autobiographical, lived experience. Without unique episodic context, AI interpretations converge toward statistical consensus.

III. Synthetic Lived Experience

This essays circles a very big and under-explored question in AI research: how to engineer the raw materials of imagination? I have written about this in the past.

History shows that paradigm-shifting breakthroughs — from Einstein’s dream of sledding at the speed of light to Descartes’ “Philosopher’s Dream” to Kekulé’s snake swallowing its tail — emerge from from the collision of personal, emotionally charged lived experiences with an existing body of broad knowledge.

This autobiographical grounding, episodic memories rich in sensory detail, meaning, and causal structure, shaped how these thinkers interpreted the world and allowed them to generate insights that no purely rational process could predict.

Current AI systems, no matter how vast their training data, resemble scholars who have read every book but never lived a day; they lack a coherent self-history, embodied causality, and the emotional weight that colors human thought.

Synthetic lived experience could change this, giving AI a believable, causally coherent autobiography that allows it to interpret facts through a unique lens, fostering divergence in thought between equally intelligent systems and enabling “weird but plausible” creative leaps. This would enable unique internal worldviews and divergent imaginative outputs between otherwise identical AI systems.

How do we give AI a believable autobiography?

For AI, a synthetic lived experience is — by definition — fictional. But fiction has always been one of humanity’s most powerful cognitive tools, letting us run safe simulations of danger, complexity, and the unknown.

Einstein never actually sledded at the speed of light. Kekulé never saw a literal serpent devouring its tail. Mendeleev never stood before a physical periodic table arranging itself in perfect order. These were fictions — coherent, emotionally charged scenarios their minds constructed from memory and knowledge — and yet they seeded breakthroughs that changed the course of history. Synthetic lived experience aims to give AI the same gift: a believable sequence of causally rich “memories” dense with context and consequence, so it can draw unexpected analogies and make non-consensus leaps. The fiction is not the point — the point is that, like humans, the AI will have experienced enough structured make-believe to imagine what has never been.

The question before us is then what lived experiences combined with what general knowledge will produce the imagination comparable to a Descartes or an Einstein? What is the proper weighting and relationship of the two? These are questions worth exploring.

Here is a proposed framework to building synthetic lived experience:

Curated Synthetic Episodes: causally coherent events with sensory detail, emotional resonance, and consequences.

Semantic Grounding: integration with general world knowledge.

Retrieval & Reflection: episodic recall for planning, analogy-making, and creativity.

Integration Mechanism: the ability to fuse episodes and concepts into novel scenarios without external prompting.

Autonomous Simulation: a private dreamworld where it can explore counterfactuals, have dreamlike recombination recombine, and imaginative rehearsal.

IV. Conclusion

Reason is powerful but fundamentally bounded by the inputs it receives. In dreams, however, the mind is not constrained by physical laws or immediate utility. It operates in a combinatorial playground where memories, symbols, and abstract concepts collide in improbable ways. These collisions often yield surprising coherence, and sometimes, transformative truth. For AI, a synthetic life history would serve as the memory substrate from which such collisions could occur. Without it, there is no private space for recombination — only the statistical remixing of public data.

The implication is profound: creativity emerges from the collision of unique, context-rich lived experience with broad semantic knowledge, and by engineering this interplay in AI — through episodic memory, semantic grounding, and autonomous dreamlike simulation — we could unlock a form of machine imagination capable of generating genuinely original theories, inventions, and cultural contributions. If we fail, AI will remain trapped in the shallows of consensus, forever brilliant yet forever derivative.

Interesting. I love this part" we could unlock a form of machine imagination capable of generating genuinely original theories, inventions, and cultural contributions. If we fail, AI will remain trapped in the shallows of consensus, forever brilliant yet forever derivative "