Signal Leverage

On Listening to the Private Markets, Amazon Aggregators & More

The public markets are hyper efficient. The market constantly digests information (whether that be earnings, job data, public policy) and transacts based on varying opinions to reach a conclusion on value. In the long run, the accuracy of the conclusion is recorded based on the performance of those that are long (those who agree with the conclusion) or short (those who disagree with the conclusion). In the short term, the market will generally signal its conclusion based on the direction of the asset price. So, it is quite easy to 'listen to the market' and identify certain signals.

The private markets, especially early stage venture, are far less efficient. In a lot of ways, this is what makes it an attractive asset class that continues to see increased allocation. Inefficiencies lead to alpha.

The mechanics that create these points of friction are interesting to dissect. To begin with, for all intents and purposes, you cannot short a position. This means that if two parties in the market receive and digest the same information and come to opposite conclusions, there is no way for them to transact and for the market to reach a consensus on fair value. Instead, price is determined in an echo chamber of likeminded parties. These parties have all reached the same conclusion — the investment is interesting — and value is determined based on who is willing to pay the most (most of the time).

However, good decision making requires a forum for dissent. As Annie Duke writes in Thinking in Bets:

Whether it is the forming of a group of friends or a pod at work—or hiring for diversity of viewpoint and tolerance for dissent when you are able to guide an enterprise’s culture toward accuracy—we should guard against gravitating toward clones of ourselves.

Instead, the venture market falls victim to confirmation bias. That's what leads to inflated valuations. Scorecards only record confirmatory positions; accountability is tough to come by.

While the lack of dissent hampers the ability to determine fair value, private markets are still sufficient at signaling what it finds interesting. In fact, given the degree of friction that occurs in transacting in the private markets, when a group of diverse investors reach a consensus in a relatively fixed timeframe, the signal is quite profound.

This post will focus on two questions: .

Why are signals important?

How do you determine a signal in the private markets?

Why Signals are Important

The rate of change in business continues to accelerate. Technological adoption is occurring faster, deals are closing quicker, and human knowledge compounds.

In his most recent memo The Winds of Change, Howard Marks reflects on this new world order.

Today, unlike in the 1950s and ’60s, everything seems to change every day. It’s particularly hard to think of a company or industry that won’t either be a disrupter or be disrupted (or both) in the years ahead.

For investors, this means there’s a new world order. Words like “stable,” “defensive” and “moat” will be less relevant in the future. Much of investing will require more technological expertise than it did in the past. And investments made on the assumptions that tomorrow will look like yesterday must be subject to vastly increased scrutiny.(emphasis mine)

Indeed, a common point of reflection amongst a number of prominent investors in the later stages of their career is the simple idea that, more times than not, rates of change are non linear.

Yet, the idea that things compound is a difficult one to conceptualize. It is what Einstein saw as the 8th wonder of the world and the most powerful force in the universe. Hence Compounding Thoughts.

Specifically, Einstein’s special and general theories of relativity abandoned the idea of a single line of time along which causes and effects can be strung. Instead, he found that time is warped by the presence of large masses.

A similar phenomena holds true in the world of economics. For almost 2 million years, human progress was tied to laws of nature, where we progressed only as much as our biology saw fit. This progress came slowly, at a constant linear rate of change with no externalities bending our plane of progress.

But eventually that changed. Powered by innovations in thought (the Enlightenment) and technology (the Industrial Revolution), there emerged new masses dense enough to manipulate our trendline and create subsequent nonlinear and compounding pathways.

As a result, technology rather than biology became the dictating force of human progress. Just look at population growth over time.

Or pretty much any other metric on progress.

This is because once an innovation passes over the singularity of impossible to possible or nonexistent to existent, the subsequent evolution almost always behaves nonlinearly.

The Law of Accelerating Returns states that the rate of change of progress accelerates because humans can use the technology at their disposal to progress faster than previous generations could without the technology.

For example, at the turn of the 20th century, a single enabler shifted us from a civilization unable to fly, to one which could. Progress in aviation — and space exploration — has been rapid since, the record distance increasing nearly 150,000-fold from 0.28 kilometers in 1903 to just under 41,500 kilometers in 2006.

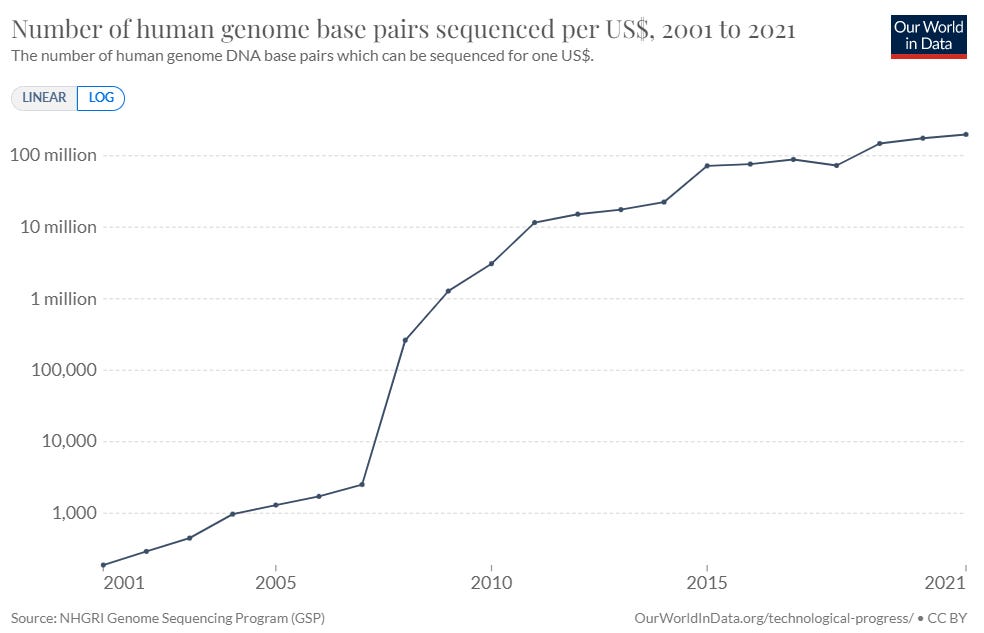

Another example which demonstrates this non-linear progress is the field of human genome DNA sequencing. The Human Genome Project (HGP), which aimed to determine and map the complete set of nucleotide base pairs which make up human DNA (which total more than three billion) ran over 13 years from 1990-2003. This initial discovery and determination of the human genome sequence was a crucial injection point in the field of DNA sequencing.

In sum, as technology compounds and the human spacetime plane warps and warps, the existing rate of adoption continues to increase, and innovation on top of innovation creates compounding effects. These new economic masses ('technology') become even more massive and composable in nature, and the existing economic spacetime welcomes it at increasingly steep slope.

What is 'spacetime' in this context? One such definition is progress, but another of equal merit is entropy. Since change happens faster and with more magnitude, the future becomes increasingly harder to predict, and with it the presence of unknown unknowns more and more prevalent.

The consequences of this are hard to grasp. Betting against technology and innovation has proved to be a bad bet over time, yet accurately predicating the future becomes harder as the ground beneath are feet changes at an accelerating pace. By the time we can figure out the rules of the present, the rules have already changed. For industries that rely on probability and triangulating future outcomes, it is essential to focus on changes to a system's interconnections rather than its elements.

This leads to the importance of signal leverage. When certain externalities have a high probability of causing an element to change, rather than focus on whether change will lead to a good or bad outcome, focus on how change will affect the interconnectedness of the system. Said another way, the more interesting course of action is to leverage the work already done and focus on the derivative of the consensus.

Determining a Signal

Signals are powerful tools to help back cast from a future state and identify particular inflections that are consequential to getting there. Signals are beacons that, in the ever accelerating world of change, crystalize velocity from speed — implying a direction rather than just sheer momentum.

I believe signals in the private markets have four elements:

A Spark

leading to Capital Inflows

Based on Quality Decision Making

and a Secret about the Future

To work through these elements, let's also examine the Amazon Aggregator space as a case study.

A Spark

The Spark is the underlying kernel that ignites a signal. Usually, it is in the form of a transformative technology or innovation that pushes the impossible to the possible, creating new complex systems.

For the Aggregator space, the spark came in the form of innovation rather than technology. The rise of Amazon's third-party marketplace and FBA businesses enabled a new type of merchant to exist, and these Aggregators have identified these mom-and-pop stores on Amazon or Shopify as undervalued assets. Even more, they discerned that additional value could be unlocked via consolidation.

The Aggregator model has four parts:

Data focused approach that uses third party tools to identify outperformers.

Establish an operational layer that creates synergies with the acquired brands, investing in merchandising and marketing and verticalizing supply chains.

Accelerating the business with brute force.

Winners will innovate and move quickly as marketplace continues to grow ($80B in gmv in 2020), creating winner-takes-most effects.

As a result, Amazon seller valuations have doubled since the start of 2020. Amazon private label sellers are getting acquired for SDE/Adjusted EBDITA multiples of 4x - 8x, plus an earn-out that could bring the total valuation north of 10x. At the start of 2020, average valuations were starting at 2.5x - 3x.

Capital inflows

Capital (both financial and human) tend to follow the original spark. With it comes a brute force that can't help but push the future in a certain direction.

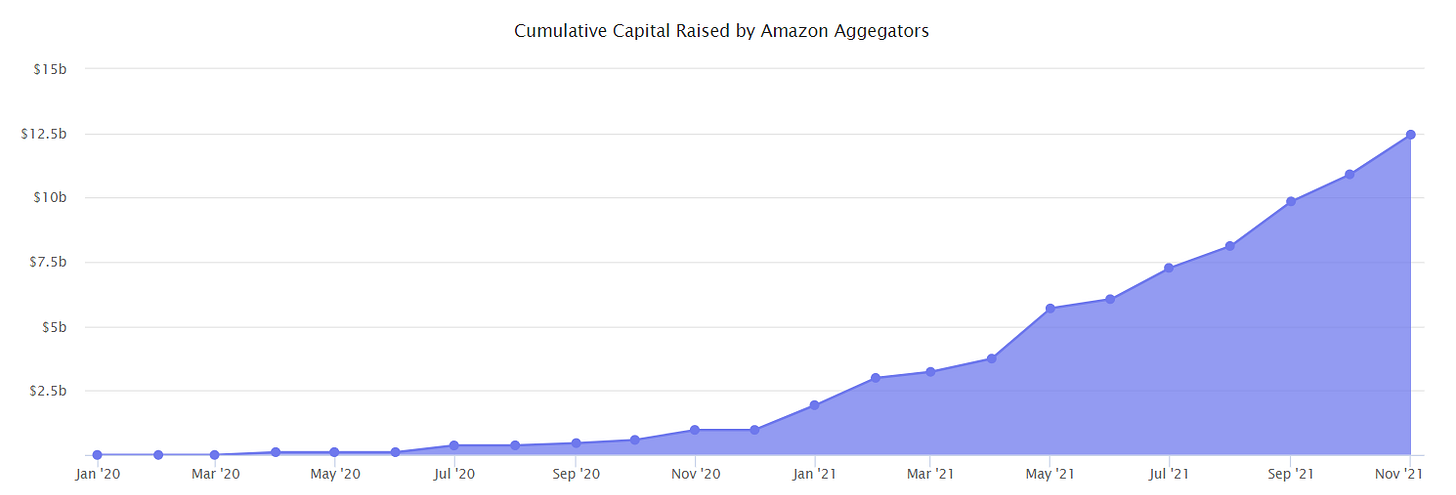

After the first few Aggregators (namely Thrasio and Heyday) raised capital to execute the original spark, the subsequent fundraising velocity and magnitude in the space has been nothing short of remarkable. Six out of the first eight months of 2021 Amazon Aggregators raised at least $500 million. Twenty-five Amazon Aggregators have raised at least $100 million. Since the industry kicked off in April 2020, they attracted over $12.5 billion — practically all of which came in 2021 by 38 different companies.

To provide some perspective, that is more than triple the cumulative capital raised by DTC beauty and fashion brands over a decade. Glossier, Skims, Allbirds, Everlane and Function of Beauty are just a few unicorn brands within that universe.

Quality Decision making

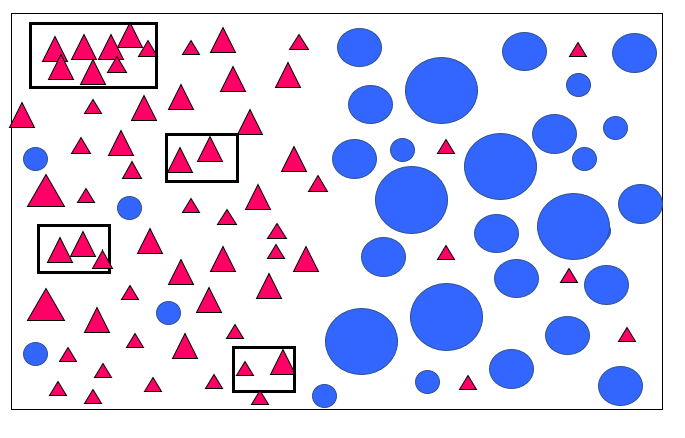

Quality decision making usually has two key attributes that lead to a consensus: diversity and dissent. As we know, the private markets lack a mechanism for dissent, and sometimes other forces — such as confirmation drift — can lead to a spark receiving inflated capital inflows that lack merit.

In the absence of a bilateral market that permits dissent in its decision making, the diversity of the investor base proves to be a valuable census in determining the goodness of a signal; or at least that multiple perspectives, worldviews, risk profiles and investment strategies agreed on the thesis overlaying it.

In the case of Aggregators, very rarely do you see a collection of materially different investors concentrate on a particular theme in such a short period of time, and especially not in CPG/retail. Yet, Aggregators have attracted a diverse investor base, ranging from early stage venture and growth funds (Khosla Ventures, Spark Capital, Softbank), to fundamental-driven private equity and alternative asset managers (Advent, Oaktree), to institutional lenders (JP Morgan). Not only does this demonstrate that a group of investors with inherently different perspectives, incentives and strategies have reached similar conclusions (diversity), but it also reveals that a market emerged to facilitate different forms of transactions (venture capital, growth equity, private credit) almost simultaneously, serving as a brake to confirmation drift as investors have multiple means to transact given various risk profiles.

A Secret about the future

The output of the original spark is a shared secret about the future, one that the capital inflows will build toward. Identifying this secret(s) is the purpose of signal leverage.

In the case of the Aggregators, there is limited differentiation amongst them. Sure, each has a unique framework to identify potential acquisitions and streamline operations to unlock efficiencies, but by and large very little separates one Aggregator from another.

Clearly, given the number of Aggregators that have raised substantial capital, the geographical distribution amongst them, and the commodity-like nature of the category as a whole, the thesis here is a macro one. These Aggregators have identified a secret about eCommerce, specifically Amazon’s third-party marketplace, and have integrated it as fundamental to their model. A diverse group of investors have bought into this secret and provided the capital to help Aggregators built toward it. While the outcome is difficult to discern, there are certain elements that have high probability of occurring as they execute to get there.

So, what could they be in the context of Amazon Aggregators? Let’s briefly examine a few.

Brand on Amazon

Perhaps more so than anything, Aggregators have identified a secret about consumer behavior that is often overlooked, and which Amazon has brilliantly nurtured for years. While Amazon's has integrated search, supply and fulfillment, they ultimately gain consumer trust through distributing brand to consumers via ratings and reviews.

In essence, brand on Amazon has been quantified. 78% of Amazon searches are unbranded, according to an analysis by Marketplace Pulse, as high-intent consumers rely on reviews and ratings to determine which product to buy.

Amazon Investing in Complementary Network Effects

Amazon has launched a number of programs and products that signal long term commitment to the third-party marketplace business, many with a wink to Aggregators. Amazon announced their Brand Referral Bonus Program, which "credits brands an average of 10% of sales from traffic you have driven to Amazon.” Meaning, if a customer is acquired via an advertisement on Instagram, the merchant will only pay a 5% fee compared to the 15% fee it would pay if the customer found the brand on Amazon.

Amazon also recently announced the launch of its Product Opportunity Explorer, a new tool to help third party merchants on their marketplace identify subcategory trends and grow their businesses across categories. Previously, companies like Jungle Scout and Helium 10 have scraped data from the Amazon marketplace to offer similar insights. Clearly, these moves favors Aggregators who have the labor capacity to effectively leverage the tool to identify opportunities and execute on them quickly, as well as the cash flow to advertise off platform and earn better economics in the process compared to their independent counterparts.

This all coincides with two additional strategies on the platform — growing the advertising business (which you can read about here) and investing in discovery that demonstrate a strong commitment to the third-party marketplace ecosystem.

A Focus on Discovery

Since aggregators have modularized supply and integrated user experience (better data and marketing) with distribution, they have a ton of flexibility with how to use their contribution dollars.

Most likely, they will use the contribution to i) acquire new brands and ii) advertise off Amazon on FB/Google and elsewhere. As they do, they continue to concentrate consumer demand on their platform, winning on price, hacking brand (through reviews and ratings), and spending more on Amazon ads. If consolidation causes downward pressure on price and more expensive ads, the impact on independent merchants’ cash flow — as well as new merchants start up costs — could prove fatal. Coupled with rising multiples, we may quickly see a tipping point in supply of FBA businesses, which would lead to further acceleration of capital inflows of the Aggregator space. $12B could be $30B by the end of 2022.

You can almost think of Aggregators as large masses slowly warping the Amazon spacetime. As they do, they use the contribution dollars to make themselves larger and strengthen their gravitational force on consumer spending and digital advertising.

Over time, the atomic unit changes.

This is music to Amazon’s ears. While existing search and banner ads will become more expensive, Amazon’s build out of discovery, social commerce tools (such as livestreaming) and emerging creator community will enable new types of ad products and direct attribution that should subsidizes ROAS and add elements of brand awareness that previously didn’t exist. This should also increase traffic time on the platform, as well as the opportunity cost of not being on Amazon for first party vendors.

Closing Thoughts

It is a fair bet that the future will look different than today, in fact, that is the lynchpin that ties all venture capital strategies together. Directionally, innovation and capital are two vectors that drive towards that future. With each day, more vectors emerge, all of which travel at greater velocities. These create more chaos and more collision — of ideas, of systems, of technologies. The consequential friction releases itself in the form of kinetic energy — the unknown unknowns of the future — which themselves greatly impact the state of things.

So, instead of determining whether a signal leads to a good or bad outcome, rather the more interesting course of action is to quickly determine the quality of the decision making that led to it, and then to leverage the work already done and focus on the derivative of the consensus. In a world that is accelerating, it becomes essential to compound your decision making akin to how technology compounds.

Knowing these elements should allow you to quickly diligence signals and start thinking in second order effects. This becomes more consequential given that decisions in the private markets are unilateral (only confirmatory). As such, there is little to gain (at least monetarily) from doing the work to determine if a market signal will lead to a bad outcome for those involved. Rather, there is a lot to gain by grounding yourself in a future that is easier to grasp given clear information on where it is heading and the finite ways it can get there.