Making Sense of the Macro

Inflation, Interest Rates, The War in Ukraine & Commodity Prices, Labor Markets and The Great Repricing

The past few months have been…uncertain. In our great economic cauldron, more and more elements are being added to the alchemy of macroeconomics. Inflation. Interest rates. Supply chain. Commodity prices. The War in Ukraine. Labor Markets. Valuations.

It’s a lot.

This post will seek to provide a simplified, just-under-the surface overview of the major macro headwinds that have begun to impact both the markets and the economy.

I will break down each of these topics so that the average reader leaves with a solid foundation from which she can depart to conduct her own research. Specifically, upon reading this piece, you should be able answer the following questions:

What’s going on?

How did we get here?

What does it mean going forward?

Lastly, I will then discuss how this has led to the Great Repricing. The goal, in a way, will be to clearly explain to founders how the current repricing in the public markets will directly transcend to the private markets, and that they must temper expectations accordingly.

With that being said, I am not a macroeconomist so do not view this post as gospel. Make sure to do your own research.

Let’s begin.

Inflation

In the most simplistic sense, inflation is caused by too much money chasing too few goods and services. So, inflation can be caused by:

An increase in money supply

A decrease in the production of goods and services

A combination of both

The inflationary impact of the government’s stimulus response to COVID-19 are well documented, so I will not beat an old drum. A picture says a thousand words, as does the chart below. The punch line: in 2020, we printed nearly $10 trillion dollars of money and increased the currency in circulation by 5x.

Many believed this was excessive.

At the same time, Covid-19 completely changed consumer behavior as entire service-based industries shut down. Instead of going to restaurants and night clubs, we bought groceries and sourdough starter. Instead of going to Soul Cycle, we bought a Peleton.

As a result, demand for goods skyrocketed. Restaurants, salons and other services struggled to staff enough employees necessary to function, and further COVID restrictions limited the capacity — and spending — of theses businesses by over 50%.

These two forces overwhelmed global supply chains. Manufacturers and vendors could not keep up with the demand for these products. For most of 2020 and 2021, even Amazon struggled to find warehouse space to store additional inventory for sellers, forcing them to scramble to find alternatives.

Adding insult to injury, international logistics and transportation networks responded to COVID differently. Across the world, the rules that defined what constituted essential workers differed, so many occupations that were critical to the production and movement of goods were barred from going to work. Some viewed truck drivers and port operators as essential workers, others did not. China, which makes up 28.7% of the total global output for manufacturing, shut down their ports and created a logjam of carriers waiting to pick up finished goods.

This persists even today, where China’s zero COVID-policy has shut down production in major manufacturing cities.

“Everything in China is a mess right now in terms of China’s connection to global supply chains,” said Andy Rothman, an investment strategist at Matthews Asia.

“In the last two years, Americans are buying more physical products as opposed to services, and many of these physical products are coming from China, so it has a bigger effect on the U.S. economy,” Yasheng Huang, professor of global economics and management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School, added.

Containers from China only recently went down from costing ten times more, but are still taking three times longer to import. Consequently, lead times for products went from 90 days to 9 months.

So, the initial shock in demand for products became more sustained, and while we flooded the economy with more money, we also had — and continue to have — prolonged months of under production and supply chain bottlenecks. This puts more pressure on global supply chains that lacked the resources and breathing room to fix the structural issues that emerged under pressure.

In addition, we had a one time massive injection of money supply into the system that for months slushed around the economy chasing too few products (given supply chain crunch) and too few services (given labor markets and capacity restrictions).

And so inflation started getting out of hand. Then the War in Ukraine happened.

Food Commodity Prices & Inflation

Russia and Ukraine supply 28% of globally traded wheat, 29% of the barley, 15% of the maize and 75% of the sunflower oil (The Economist). Sanctions on Russia, and the blockade of Ukraine’s ports, have removed a majority of these commodities from the global market.

Ukraine produced about 80 MMT of grain (a category that includes wheat, corn and barley) in 2021, and is expected to harvest less than half of that this year.

A shortfall of 40 MMT is enough missing calories that a country like the UK could only make it up by having everyone stop eating for three years.

Consequently, commodity prices are through the roof.

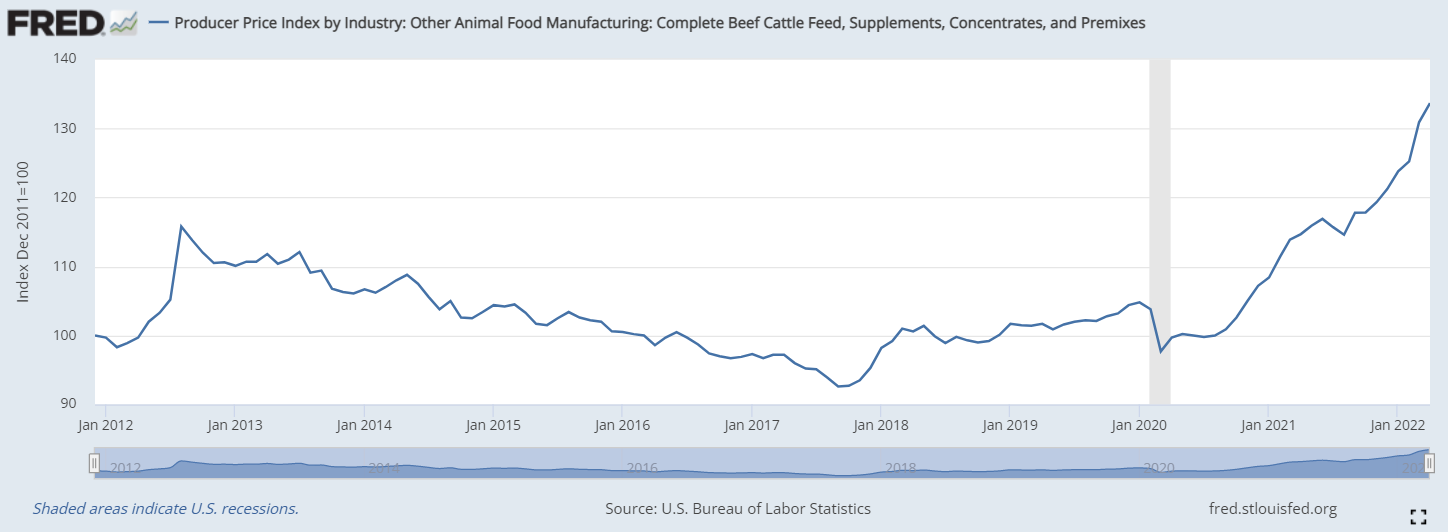

Indeed, a large portion of the global population’s diet relies on grain staples like wheat, corn and barley. More, these staples are a main input for livestock feed.

Thus, a massive decrease in the global supply of grains not only increases the price of these staples, but also increases the price of feedlot, which impacts chicken, pork, beef and dairy prices.

Chicken

Beef

Dairy

Pork

So we get headlines like this.

On top of that, farmers are struggling to make up the shortfall in supply, in part because profit margins are being squeezed by the surging cost of fertilizers.

Fertilizer prices are increasing because Russia accounts for 21% of the global potash market, a main input of fertilizer, according to Jason Troendle, director of market intelligence and research at The Fertilizer Institute.

So, farmers are getting squeezed. Their two main inputs — feed and fertilizer — are very quickly bleeding their profit margins and putting their unit economics under water.

Farmers like Don Tharr, who along with his sons, runs Black Walnut Farm — a 2,000-acre operation in Warren County, have seen astronomical price movements. The fertilizer in Tharr's storage barn cost him $120,000 two years ago. The same amount costs him close to half a million now.

For many farmers, high yield production has become cost-prohibitive and they are forced to plant smaller yields. In other parts of the country, some farmers are changing what they grow entirely.

This is a dangerous spiral as we need these farmers to grow wheat, corn and other grains to compensate for the future harvest loss in Russia and Ukraine and put downward pressure on commodity prices.

More, global ending stocks for the major global exporters of wheat are expected to decline considerably compared to 2020/21 — to the lowest ending stocks since 2007/2008.

Around the globe we are seeing dramatic policy changes in response to this stock shortage. As of mid-May, the India Government imposed restrictions on wheat export owing to multiple reasons, including hoarding of Indian wheat by China and lesser production of wheat compared to previous years due to poor weather and rising fertilizer costs.

Gro Intelligence also points out that global fertilizer prices have tripled over the past year, risking "significant" reductions in crop yields this year. As a result, the gross revenue for wheat exports don’t cover even the landed cost of imports.

This is a significant policy change for the second biggest wheat producer in the world. Although India accounts for 1% of the global wheat trade (keeping most of it to provide subsidized food for the poor), before announcing the ban, India was aiming to boost exports by shipping a record 10 million ton of wheat this year - a 400% increase from the year before.

Kelly Goughary, of the agriculture data research group Gro Intelligence, explains that India's ban led to a further price surge because "global buyers were depending on supplies from India after exports from the Black Sea region plunged."

While India is less of a player in the global grain markets, it is a critical supplier to main countries in its region that rely heavily on Indian grain imports to feed its populations.

In 2019-20, Sri Lanka and UAE imported more than 50% of their wheat from India, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), and Nepal imported more than 90%.

Food insecurity has already begun to destabilize the region. In Sri Lanka, a two-month long escalating protest over soaring consumer staple prices and power cuts has rocked the nation. The Prime Minster resigned. More than 50 houses of politicians were burned down. Now, Sri Lankan security forces have been ordered to shoot law-breakers on sight in a bid to quell anti-governmental protests on the island.

Consequently, global wheat production for the 2022-23 period will be the lowest for four years, and global stocks of wheat are predicted to be at their lowest for six years, according to a US government report.

China — the world's largest producer of wheat for its huge population — said in March that its winter crop could be the "worst in history" because of heavy rainfall in 2021. If it is, China may want to buy on global markets to build up its stocks, further tightening global supplies and pushing up prices.

Thus, global wheat market will continue to struggle to meet the demand amid Russia’s ongoing military action against Ukraine, putting upward pressure on food commodities.

While U.S. Department of Labor statistics showing food prices on the rise for 17 straight months, many believe that the impact of Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine has yet to fully flush through the system and that increases in food prices will persist in the near future.

In fact, since 2020, the Consumer Price Index of food items has significantly diverged from overall CPI.

Meaning, food prices are increasing at a greater rate than overall inflation.

In April 2022, food prices are up 14.35% from a year ago while CPI is up 8.22%. The spread is greatly above the median and historical trendline, suggesting that food inputs are an even greater force behind inflation, and behaving countercyclical to previous economic downturns (2000-2001, 2008-2009) when the spread was significantly negative (food prices increase at a much lesser rate than overall inflation).

Plotting a normal distribution chart of the spread data shows how extreme of an outlier the Food vs. CPI spread currently is.

Combined with all time high energy prices due to sanctions against Russian natural gas and oil, pivotal commodities are threatening the economic models of industries like farming, agriculture, mining and energy production.

Impacting Demand

The prices of the three main non-discretionary household expenses — housing, food and energy — are increasing because of non-cyclical externalities (COVID-19, the Feds response to inflation, and the War on Ukraine), which will further destroy demand and put pressure on many companies’ operating margin.

This is exacerbated as many companies — across industries — have over-stocked, over-invested, over-hired, and over-built due to misreading the market and believing the demand spike in 2020 and 2021 was durable instead of transient.

As a result, these companies doubled down on production and human capital to service this transient demand. They believed this was a sustainable accelerant to their growth and invested in long term projects to support it. But in reality, they were getting fat today on tomorrow’s customers.

Even Amazon fell victim to it. Remember when Amazon didn’t have enough warehouse space in 2020 and 2021 to service demand?

Now, nearly a year later, Amazon estimates that excess space will add about $10 billion in costs in the first half of 2022, more than its projected operating income. Amazon's operating income was $3.7 billion in Q1 FY2022, and the company's guidance indicates that it expects Q2 FY2022 operating income to be between a loss of $1.0 billion and a profit of $3.0 billion.

That’s an out-of-character, egregious miscalculation for one of the best run companies in the world. And if Amazon made such a mistake, it’s a safe bet that many others did as well.

In fact, both Walmart and Target announced in their Q1 2022 earnings calls that they were caught off guard by a rapid retrenchment among consumers at a time when they were carrying a higher than usual level of inventories.

Target’s product inventories were up 43% from last year, while Walmart’s was up 32% from the previous year. Even apparel brand Abercrombie & Fitch’s inventory increased 45% year-over-year.

Consequently, Walmart’s operating income was down by $1.6 billion this quarter. Its bottom line had taken a hit from staffing challenges, high fuel, storage and container costs, according to Walmart executives. Target’s operating income, on the other hand, declined 43% year-over-year, which the company said was a result of shifting consumer spending away from discretionary goods.

"U.S. inflation levels, particularly in food and fuel, created more pressure on margin mix and operating costs than we expected. We're adjusting and will balance the needs of our customers for value with the need to deliver profit growth for our future." Walmart CEO Doug McMillon said.

Along with the drop in general merchandise sales, Walmart is seeing other signs that some households feel budget strapped. The average ticket for customers in the U.S. rose 3% due to inflation, but the number of items in baskets has fallen, McMillon said on the earnings call. Walmart is trying to strike a balance between keeping prices low, while not letting profits slip further, McMillon told analysts.

To date, Walmart has done a good job at keeping prices low. But as Walmart seeks to cushion the impact of their double-digit cost increases, they will have to pass on more than the current 3% cost hikes to consumers. In fact, Walmart executives signaled the possibility of raising prices to recoup profits during the earnings call.

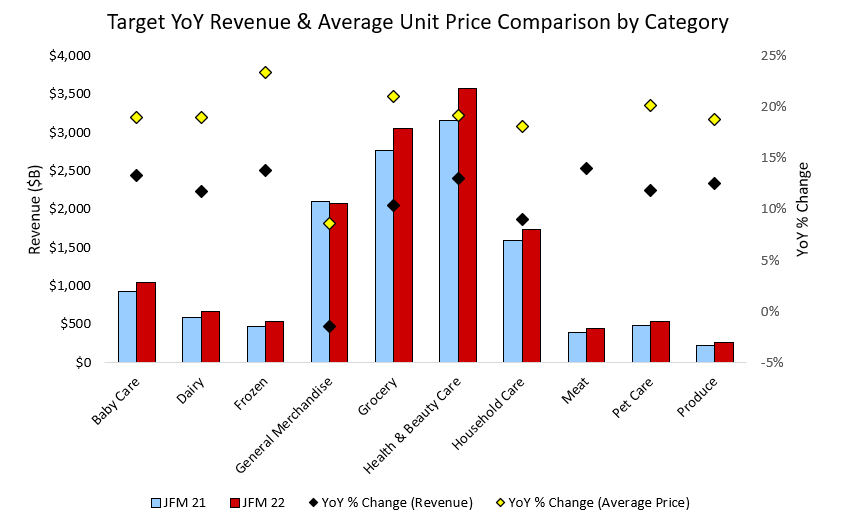

Target, meanwhile, has already significantly raised prices across categories.

“While we’re not happy about the near-term pressure this causes on the profit line, we strongly believe these decisions will benefit our business over time,” said Target CEO Brian Cornell.

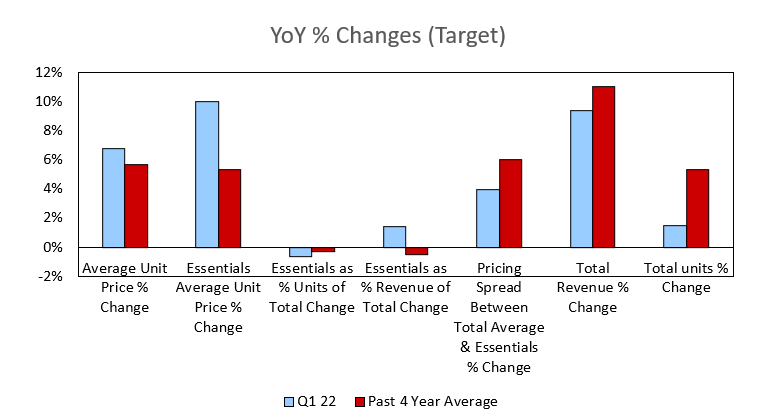

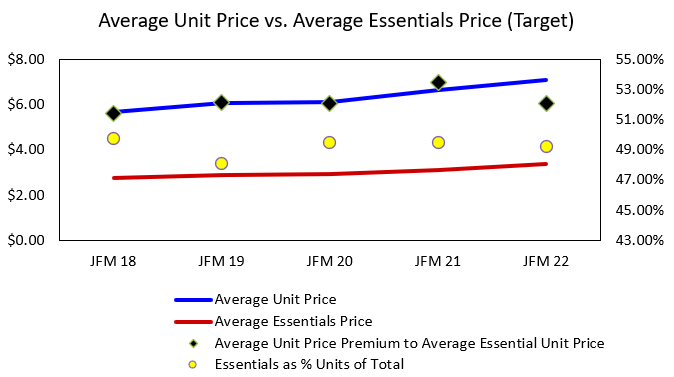

Indeed, Target is heavily dependent on price increases to maintain revenue growth amid weakening demand and lower items per basket. Across categories, YoY change in average unit price is increasing at a greater rate than revenue growth.

Yet, while average unit price is only slightly above historical mean, total unit is well below. In Q1 2022, the spread between YoY average unit price percent increase vs. total unit sold percent increase was 5%, a 94% increase from the past 4 year YoY spread average of 0.34%.

This implies that input inflation is having an outsized impact on Target’s revenue growth and that true demand is declining compared to traditional growth trends.

On their earnings call, Walmart said food price inflation meant that customers were diverting more of their spending to essentials than it expected. Target CEO Brian Cornell cited changes in shoppers discretionary spending as well. Consequently, consumers spent less on more discretionary, and higher margin, items such as clothing and home furnishings.

Yet, consumers are buying less of essentials than we have seen historically, and we are seeing a slow down in unit velocity in Target overall. This implies that the change in consumer behavior from discretionary spend to non-discretionary (essentials) is potentially not as meaningful as stated by both management teams, as essentials as a percent of total units at Target is well below the mean of the past four years.

Indeed, the pricing spread between average unit price and essentials average unit price has not tightened, and the period of excess of Q1 2021 seems to be the outlier.

That’s because we have not yet seen the impacts of demand shifting from discretionary to non-discretionary spend but rather the impacts of food commodity price inflation being passed off to consumers.

While inflation has mainly been a supply force of rising input costs, as demand increases to normalized rate, retailers will be forced to i) accept slower revenue growth or ii) continue to raise prices in order to amortize persistent operating expenses across across transactions with fundamentally lower product margin.

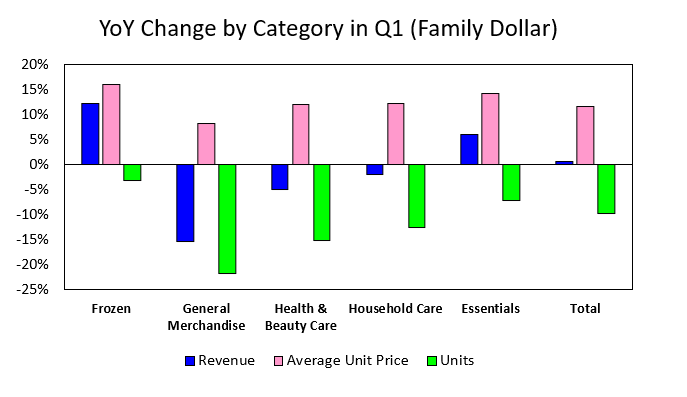

We are seeing similar consumer behavior in the dollar store category, with a significant decrease in demand for discretionary items like general merchandise and household care. And while demand overall has weakened across categories, growth is being driven by the relative spread between essentials and discretionary, both in terms of units and average unit price.

I believe that the impact of this economy-wide demand forecasting miscalculation and increase in operating expense will soon be felt by consumers, both in terms of further price increases in non-discretionary categories and disruption to labor markets.

Labor Markets

The impact on the markets, inflation and the economy have yet to hit the job markets, with new hiring still maintaining normal levels.

While COVID led to lay offs in early 2020, these employees quickly found jobs elsewhere and by mid-2021 the number of people not in the labor force but wanting a job returned to normal, pre-COVID levels.

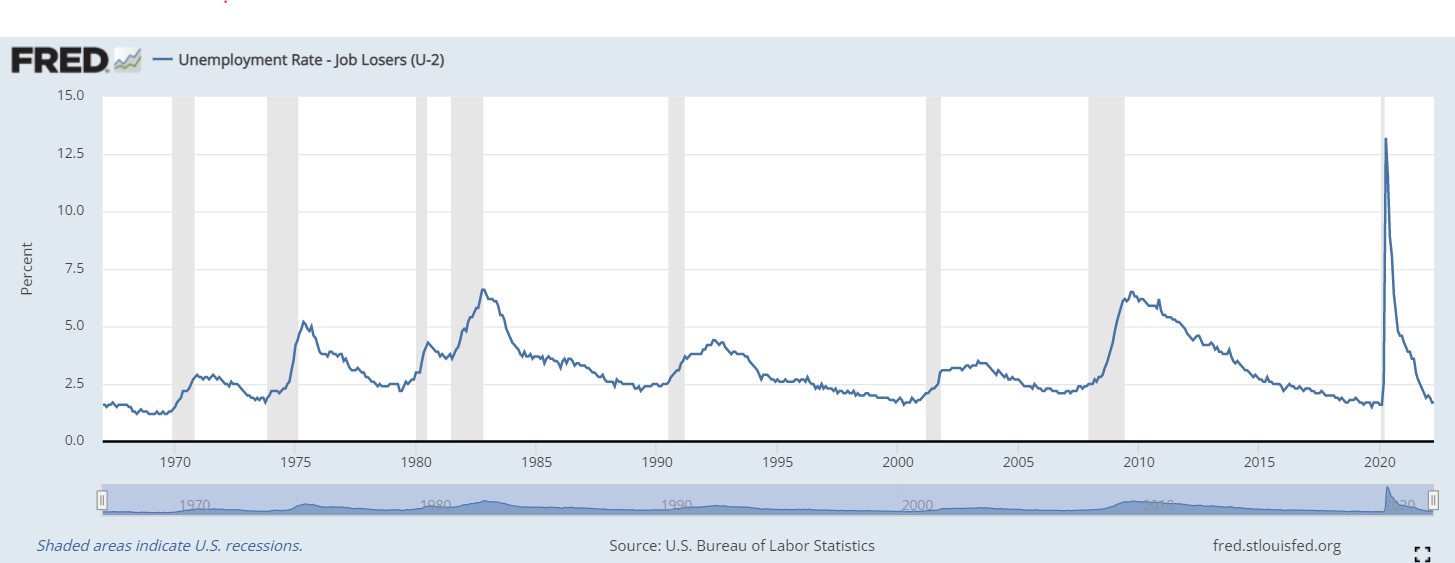

So, those that want to work are in the labor force. The unemployment rate of job losers — people who involuntarily left their job and want to work — is at an all time low.

While total job openings are up 40% from pre-COVID levels, I do not believe this is because of an impartial workforce. The same number, if not more, of individuals are in the workforce as during pre-COVID, with unemployment rate at all time low and individuals looking for jobs bottoming at pre-COVID levels.

Yet, as pointed out, companies across the board are seeing operating expenses increase at a greater rate than revenue growth.

Target on Wednesday said these factors would mean a full-year operating margin of about 6%, compared with the 8% or more it forecast as recently as early March. Amazon, as we discussed, has issued similar write downs of its operating margin.

This is caused by:

Supply chain increasing the cost of manufacturing and freight in (macro)

Rising fuel costs (macro)

Excess inventory and warehouse space (micro)

Overhiring (micro)

iOS impacts on marketing (macro)

Inflation increasing raw material inputs and COGS (macro)

Wage increase (macro)

More, the economy miscalculated demand and believed that the energy fueling growth was durable. But as this demand washes away, these jobs remain unfulfilled because:

The labor force is close to equilibrium and those who want jobs have them

Employers are not willing to pay the cost of inflation-adjusted real wages plus switching premium

These jobs are fundamentally transitory and are difficult to hire for

As such, we are beginning to see signs of a correction.

I expect this trend to continue and the labor markets will loosen for employers and tighten for the workforce.

Last week, Elon Musk announced a 10% headcount reduction at Tesla. Crypto platform Gemini has cut approximately 10% of its workforce. Coinbase recently said that it will extend a hiring freeze for both new and existing positions for the “foreseeable future” and rescind a number of accepted offers. Amazon CEO Andy Jassy has stated that his company is "no longer chasing physical or staffing capacity."

Uber, Google, Lyft, Facebook and more have frozen hiring. Many more companies have begun layoffs.

However, this alone will not serve as the remedy. Supply chain costs, inflation and rising wages are structurally issues of the economy and, in many causes, are causing a greater relative impact on operating expenses.

To help combat inflation in particular, the Fed has begun raising rates.

The Fed and Interest Rates

The Fed uses interest rates to destroy demand. They do this when the economy overheats and rely on increasing rates as a tool to pull money out of the economy by making savings more attractive and credit harder to come by.

The Fed accomplishes this by raising the cost of capital via the federal fund rate. The federal fund rate is the interest rate set by the Fed at which commercial banks borrow and lend their extra reserves to one other overnight.

Raising the federal fund rate increases a bank’s cost of capital. This trickles down to their customers — the bank will pass on this cost of capital increase by raising mortgage rates, credit card interest rates, auto loans, etc.

At the same time, banks will understand that raising rates leads to the destruction of demand, which will cause the economy to cool and slow down. Thus, if the economy slows down, wage growth slows down, housing prices decelerate (or decrease), unemployment increases, and people buy less things. This means that all of these loans become more risky. The bank will want to be compensated for this risk by:

Asking for more collateral (down payment) and reducing the distribution of credit

Adding a risk premium to credit (increasing the interest rate)

or — most likely — both.

This means that a person with a 550 credit score will have less credit available to them than as before and will have to pay more for that credit. As such, a $100,000 down payment on a 30-year fixed mortgage that once could afford a consumer a $500,000 home now can only afford her a $400,000 for the same monthly debt servicing payment. Home prices — and the median family’s net worth — thus decrease.

At the same time, the interest rate that you are paid to keep money in savings accounts increases. This is because banks will want to borrow from consumers at a slightly lower rate than they could from other banks (your savings deposits), and with a rate hike, they can still offer a consumer a pretty compelling savings product and use that money to pay off the loan they get from the other banks. The banks make money from the arbitrage between the interest rate they have to pay you and the interest rate they have to pay the other bank using the money they borrowed from you. The higher the rate increase, the more enticing that becomes.

But the greatest threat to this calculus is inflation. If expected inflation is 5%, we have but no choice but to raise the federal fund rate to 5%. Think about, if the value of $100 today is $95 in a year, the risk free rate must compensate for this loss of value and does so by paying a bondholder — at minimum — 5% for lending them $100 as the value of $100 today is $105 a year from now.

Indeed, Lael Brainard, the vice-chair of the Federal Reserve, last week warned that the U.S. central bank may need to extend its run of half-point rate rises into September if inflation does not slow sufficiently in the coming months. Increasing rates will further destroy demand and could lead to a recession, but many fear that is a necessary evil in order to get inflation under control.

The Fed will need to act quickly.

More Money Entering the System

To pay for inflation’s impact on the cost of living, consumers are increasingly relying on credit, and total consumer loans have bounced back to pre-COVID levels. But with raising rates, this credit has become more expensive, with the bank prime loan rate increasing 20% YoY.

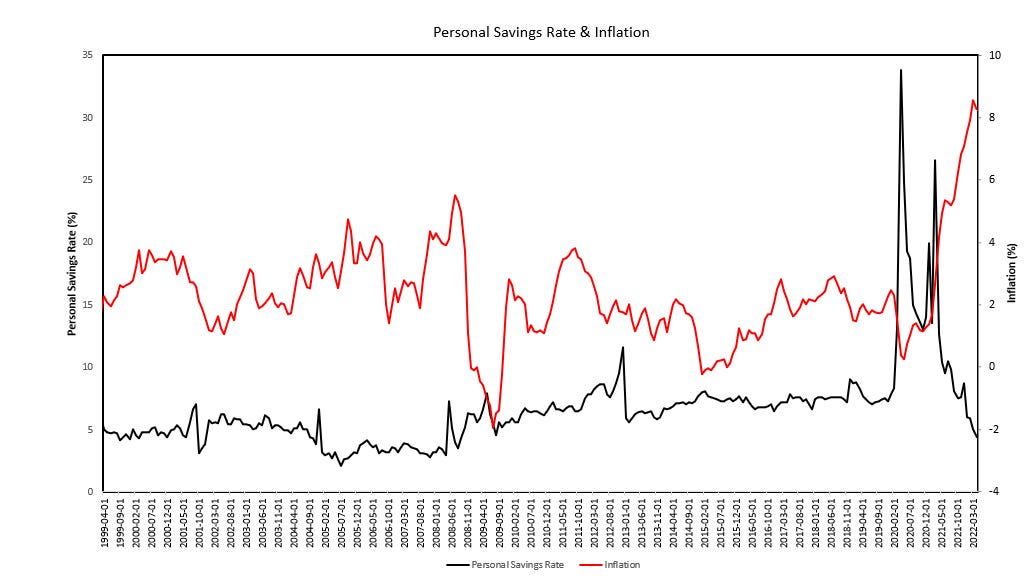

Additionally, at the beginning of COVID-19, we saw an astronomical increase in personal savings rate because of:

Stimulus injection

No need to pay rent

Fear, uncertainty, doubt

Changing consumer behavior

A brief crash of the stock market

In April 2020, the personal savings rate was 33.8%. In April 2021 it was 12%.

Now, however, savings rates are being withdrawn as consumers seek to pay off their increasing cost of capital (increase credit usage and prime rates) as well as the rising cost of living.

In April of 2022 the personal savings rate was 4.4%.

So, consumers are both borrowing more money to pay for rising prices of goods and paying more to borrow that money. The combination of the increase in consumer loans and draw down of personal savings — both consequences of inflation — are dangerous opposing forces to the Fed’s desire to remove money from the economy. They are inflationary forces caused by inflation.

The Great Repricing

The stock market is a leading indicator of where the economy is heading.

Over the past few months, we have seen a massive drawdown across the market and a corresponding multiple contraction. Investors are signaling a few things:

They have less confidence in the near and mid-term growth prospects of the economy and fear a possible recession

The market believes that the Fed will continue raising interest rates, which reinforces point 1

They’re scared of inflation

How this impacts valuation

Pricing has dropped to to reflect the decrease in demand for equities. Investors are more eager to capture the upside of good companies amid heightened macro risk by lending them money, through corporate bonds and private debt, than from being shareholders in the company (which is junior in the capital stack) and taking on more risk with less downside protection.

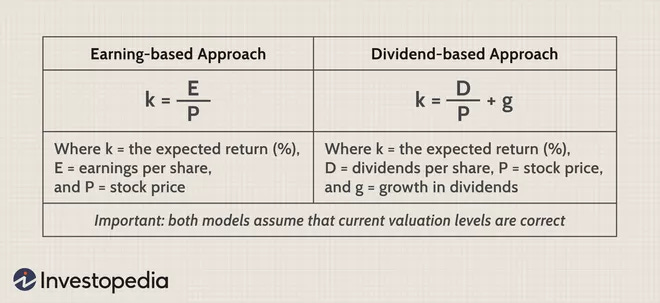

As such, investors will want to be compensated for investing in stocks over bonds, and this compensation comes in the form of excess returns. This is called the Equity Risk Premium.

But when the risk free rate increases, the market expected rate of return must increase as well. How is that possible given the uncertainty over the impacts of inflation, coupled with interest rates destruction of demand, and the recent slow down in corporate earnings?

What we have seen is that for the market to maintain equilibrium, and k (expected return %) to increase in accordance to the risk free rate when E (earning per share) is decelerating or declining while risk free rate is increasing, the stock price must decrease at an even greater rate than the earnings per share increases.

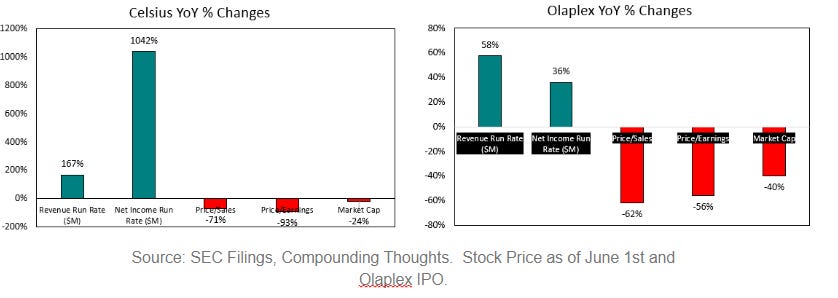

Let’s look at two attractive high growth businesses in the CPG category, Olaplex and Celsius, to see how this has played out.

In Q1 2022, both Olaplex and Celsius experienced strong revenue and net income growth.

Olaplex increased net sales 58% to $186M and net income 36% to $62M from the previous period the year before. Celisus saw net revenue increase 167% to $133M and net income increase 1,042% to $6.7M from the previous period the year before.

But amidst these apparent positive fundamental signals, Olaplex and Celsius saw their market caps decrease 40% and 24%, respectively.

Why?

While these business have become more attractive, they have become less valuable. This is because the definition of value, for the reasons I have laid above, has changed.

What investors are willing to pay for a dollar of revenue or a dollar of income has drastically decreased, and in fact has done so at a rate greater than the earnings growth of these two companies. Viewing in absolute terms:

Over the past year, both Olaplex and Celsius revenue multiples decreased at a greater magnitude (2.62x, 3.49x) than their revenues increased (1.58x, 2.67x).

The same holds true for their P/E multiples. Celisus grew its net income 11.42x to $26.7M but saw its P/E ratio decrease 14.97x (or 93%). Olaplex grew net income 1.36x to $62M but saw its P/E ratio decrease 2.26x (or 56%).

As a result, even as companies grow — both their revenue and earnings — they become less valuable in the equity markets as their value not only represents the fundamentals of a business, but what someone is willing to pay for a higher risk security amidst a higher risk environment.

Closing Thoughts

There is a terminal end point to valuation. At the end of the day, there is the buyer of last resort: that is the public markets. The public markets serves as final scale that balances ‘value’.

The important takeaway is not what the multiples are in the public markets, per se, as high growth early stage companies tend to have more upside potential and exhibit greater growth, and thus lead to a modest multiple premium.

What is important is the rate at which multiples in the public markets have changed, and how this is driven by the market pricing in more risk to the equation. Olaplex and Celsius should serve as caution signs against any hubris that valuation contractions are a reflection of business fundamentals and only bad businesses that benefitted from a surplus of cheap capital will fall victim to this repricing.

The truth is, every private company will be repriced.

Thus, if you are a private company, be diligent and plan for your next round to be done at a multiple that is a greater decrease in magnitude from your last round than the magnitude of your growth since then. Meaning, if you have grown revenue 100% since your last round that you raised at 12x times revenue, expect to raise your next round to be raised at less than 6x times revenue.

As a result, startups will be forced take an honest look at their operating expense and make hard decisions.

While incumbents are leading the way in paying inflation-adjusted wages (Walmart store managers were paid an average salary of $210,000 last year), startups will need to follow suite and be cognizant that the risk premium for working at an early stage has increased.

With public and professionalized companies demonstrating both a pull back in hiring and willing to pay more for talent, they are signaling that they want more leverage out of human capital.

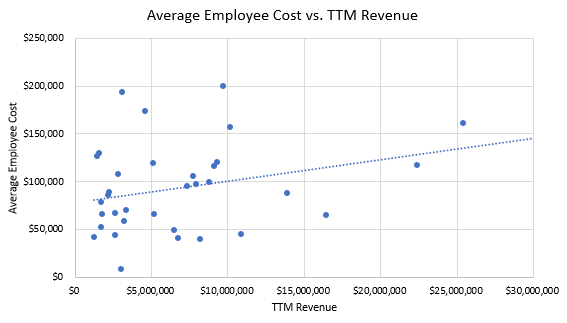

Average employee cost will increase, but so too will revenue per employee. Startups will need to react accordingly by rethinking their headcount while also paying for top employees.

To help startups navigate this decision making, I have analyzed data from 35+ startups to help level-set operating and labor efficiency.

To begin with, companies that get more leverage out of their employees see better capital efficiency and operating margin.

Yet, scaling your headcount has not demonstrated more human capital efficiency. In fact, as you hire more, revenue per employee trends downwards as the marginal return for each employee decreases.

More, there does not seem to be any relationship between increasing headcount and return on employee spend (ROES).

Or between increasing average employee cost and return on employee spend.

While you will need to hire and pay up as you grow, average employee cost should only increase modestly.

And the most efficient companies get the most out of their salary spend.

Indeed, many startups have suffered from the same labor mistakes as public companies. Many over-hired to meet the transitory demand of the past two years and will need to do more with less and focus on leveraging human capital and reducing redundancies.